Though normally sparkling and crystal clear as August draws to a close, the Mediterranean is currently troubled by politics. At the center of this new storm are the aspirations of Turkish president Recep Tayip Erdogan. It all started in mid-August when Turkey deployed an oil research vessel, the Oruç Reis, with its naval escort, to search for petroleum and natural gas in the waters near the Greek isle of Kastellorizo – waters which are claimed by Athens and Ankara as belonging to their respective exclusive economic zones (EEZ, over which a country has sovereign rights regarding the exploration and usage of resources).

The two countries then engaged in a naval power struggle which caused a collision between two Greek and Turkish war ships, pulling the region towards the kind of explosive situation that has not happened in nearly twenty years to such an extent that French president Emmanuel Macron dispatched French military reinforcements to the region.

With Egypt and France being in open conflict with Turkey and Libya, there is no longer any doubt that the Eastern Mediterranean is caught in a storm where European interests on one side and the interests of the countries of the south-eastern edge of the Mediterranean (especially Egypt, Israel, and Libya) on the other side, clash.

For decades, disputes about the region’s maritime borders were mostly a local affair, limited to claims of sovereignty between Cyprus, Greece, and Turkey. However, discoveries of large gas fields in the last few years have whetted Turkey’s appetite, which has been forcefully demanding its piece of the pie.

New alliances

From these large gas fields emerged new alliances in the region in order to secure future exports. For example, between Cyprus, Israel, and Greece or between Greece, Israel, and Egypt, with a seizable European ally – France – who, year after year under Macron, affirms its cooperation with the Republic of Cyprus in matters of defence. The French president, who believes that the EU still has too little influence in the region, is taking advantage of Brexit and the United Kingdom’s withdrawal from European affairs in order to expand the influence of France and the EU in the eastern Mediterranean.

The discovery and agreements on the exploitation of the “Zohr” gas field resurrected Cyprus’ gas industry and its capacity to be a part of regional projects, such as a gas pipeline to continental Europe. For its part, Turkey considers the potential exportation of gas through Cyprus and Greece as a threat to its own ambitions as a transit country of gas to the EU from the Caspian Sea and central Asia.What’s more, Turkey considers that the agreements on maritime border delimitation between neighboring countries are the result of a “fait accompli” and unjustly and illegally deprives it of a part of its legitimate EEZ.

Ankara, which is not a part of the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) of 1982 due to its dispute with Greece over the extent of its EEZ, signed an agreement on maritime delimitation with Libya in December of 2019. This agreement encroaches on the Greek and Cyprian EEZ and Turkey can therefore lead gas exploration in its waters as it sees fit. It is an agreement which is deemed to be null and void by the Egyptian, French, Greek, and Cyprian governments.

It is in this context that on 6 August Athens decided to get even with Ankara by signing a maritime delimitation agreement with Cairo, eliciting Turkey’s ire. A few days later, Turkey dispatched the Oruç Reis to the Greek EEZ. The European Union invariably showed its unequivocal support for Greece and Cyprus, but the Union lacks cohesion when faced with Turkey’s machinations.

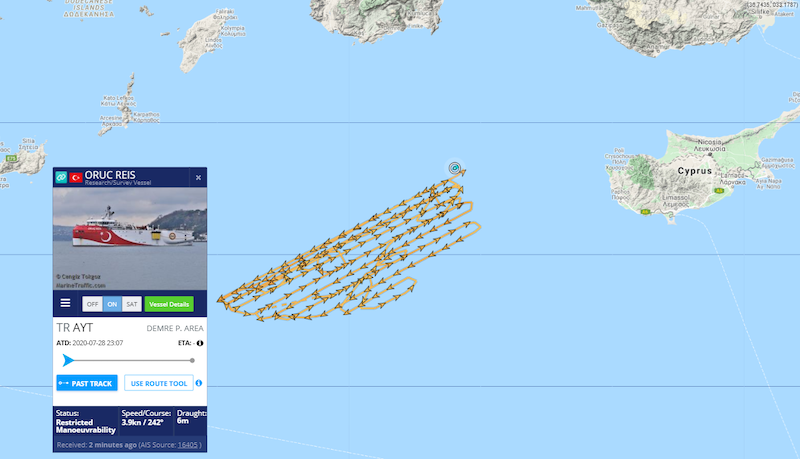

Follow the position of the Oruç Reis over the last 24 hours:

Bad cop

If Paris effectively supports the logic of sanctions against Ankara, Berlin considers them to be ineffective and is waiting to play the role of referee in disputes between Greece and Turkey. As Fiona Mullen, director of Sapienta Economics in Nicosia and consultant for the Peach Research Institute in Oslo sees it, “Germany is playing the role of good cop while France is the bad cop.”

True to its position, Berlin took note of France’s tactics in the region and called on “Paris, Athens, and Ankara” to avoid escalation in the Eastern Mediterranean. In Nicosia, it was noted that Cyprus is not mentioned in the German government’s declarations and is therefore wondering: For Berlin, do the EU’s maritime borders stop in Greece? Does it distinguish the dispute between Greece and Turkey from the Cyprus problem? Or is it simply an oversight?

Germany, currently presiding over the Council of the European Union until December 2020, is also hoping to follow a policy of pacification and cooperation with Turkey at a moment when that country is under economic pressure. And in Cyprus, the questions being asked in diplomatic circles, as reported by Cyprian daily newspaper Kathimerini, is whether the dialogue between Greece and Turkey could be beneficial for the Cyprian peace process, and if Cyprus’ problems will be put on the back burner in these attempts at dialogue taken on by Germany.

Essentially, the fear of Cyprus’ diplomats is that the issue of the island’s division becomes a “footnote” in the dialogue between Greece and Turkey, even as this dialogue is taking place in the presence of Turkish drill ships in Cyprus’ EEZ.

During this time, Turkey has intensified its gas exploration in the region by sending a third drillship into Cyprus’ EEZ, flanked by two other support ships. At the same time, on August 20th, 2020, Emmanuel Macron received German chancellor, Angela Merkel, at Fort de Brégançon in an attempt to reconcile their differences when it comes to the position to take toward Ankara’s tactics in the Eastern Mediterranean. “We can support our European partners and send ships to the scene, but we are also working towards restarting dialogue between Greece and Turkey”, declared Angela Merkel following the meeting. “We will not accept attacks against the sovereignty of European Union member states”, she emphasized.

The declaration was received favorably in Nicosia, which says it is open to discussions with Ankara on the delimitation of maritime zones on the condition that it cease violating its EEZ, all while demanding more sanctions from the EU towards them.

If Germany maintains such a position with the Republic of Cyprus while Turkey has regularly violated the Cyprian EEZ “it is because it considers that the risk of an armed conflict between two NATO members, namely Greece and Turkey, is higher”, Fiona Mullins considers. “The other reason is that the European Union’s position when it comes to solving the issue of the island’s division, is that the Republic of Cyprus return to the five-country negotiation table [Cyprus, Greece, the United Kingdom, Turkey, and the UN]. There is solidarity, but not much action”, she added.

For the Republic of Cyprus, the Turkish drill ships in its EEZ are comparable to the 1974 invasion which led to the occupation of 38% of the island’s territory by the Turkish army. Ankara is using the Turkish Cypriot minority to claim a part of the Cyprian EEZ, and thus to the gas found there. What’s more, Ankara does not recognize the Republic of Cyprus. However, “Cyprus has no other tools besides returning the negotiation table. We make do with what we have. The other problem is that the Greek Cypriots are refusing to discuss the gas issue. For them, it is a national responsibility which will become federal only in the framework of a diplomatic solution,” she pointed out.

Cyprus now finds itself stuck between a Turkish rock and European hard place, and as tension between Greece and Turkey reach new heights, it is apprehensively preparing to follow the presidential election in the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” (the “TRNC”, recognised only by Ankara), this coming October 11th. It is a vote whose result will determine the future of the peace process on the island.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!