A child who does not feel parental love, who has no one to receive love from, grows up unhappy, and is often unable to love and can do a lot of harm. The fate of the world is determined in the nursery. It is there where it is decided whether tomorrow's men and women will become healthy at heart, people of good will or maimed individuals who take advantage of every opportunity to complicate the life of their communities. The government officials who will decide the fate of people in tomorrow's world are little children today.

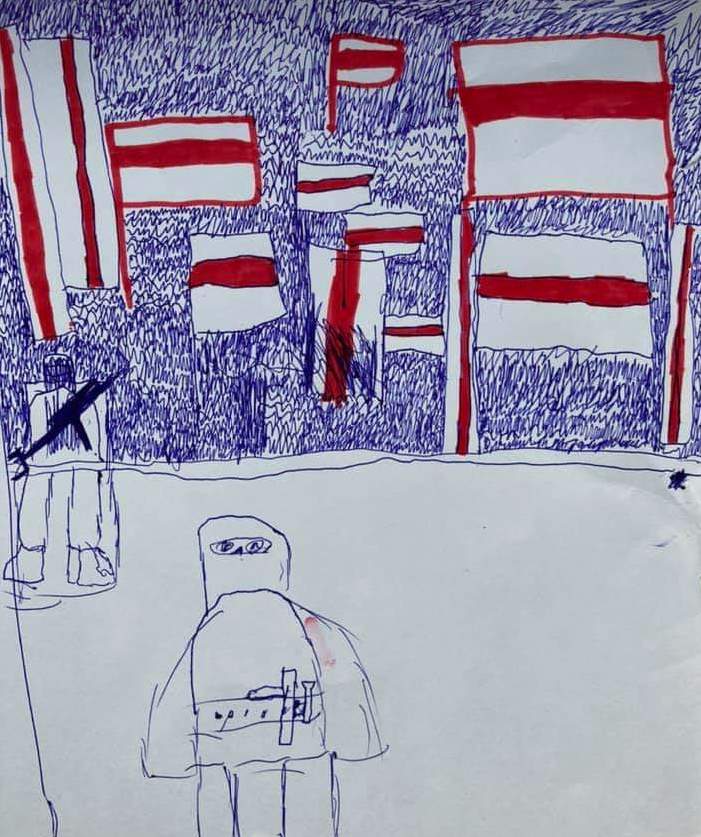

Children see what is happening in their families. A white-red-white flag hangs in the window. Parents constantly discuss something, watch the news on the Internet, every Sunday they go somewhere, and sometimes one of them does not come back home and stays in prison to await trial “for a peaceful walk”. On Saturdays, Mom puts on red lipstick, a white dress, buys flowers, and goes out into town for a walk. Grandma goes out for walks every Monday.

Children see what is happening in their yard. People gather, discuss what is happening in the country, which of the neighbors have been detained, who is in prison, people invite musicians, writers and poets to their courtyards, sing songs together, sign postcards and send letters to those who have been unjustly detained. People hang out flags in their windows and decorate fences with white ribbons.

Children see what is happening in their kindergartens. A teacher can lock a child in the bathroom, punish him or her only because while playing the child repeats what he or she hears from adults or sees on the streets of the city. The teacher says this year all the girls will dress up as Christmas trees and wear green dresses with red bows, and not as snowflakes in white dresses, as they always have.

Children see what is happening at school. Even though they are prohibited from discussing politics, they know which of their teachers worked in the election commission during the presidential elections, who was in charge of the commission, who signed a false protocol thus falsifying elections, who called riot police against people who came to the voting site in the evening to find out the results of the elections.

Children know which of their teachers refused to do this, who quit school because they could not continue to work in this system. Children see and know whose parents were arrested during the peaceful protests and which of them are in prison. Children know which of their classmates had to leave the country because their parents fear for their safety and that they will be detained again.

On Mondays, during their classes, children see from the school windows riot police disperse a peaceful protest of senior citizens and students. On Wednesdays, they see police pack paddy wagons with people with disabilities.

Children draw posters and march in a small demonstration at school. Their parents come to school holding posters, one reads "We are proud of our children." Children see their principal calling the riot police who, before their very eyes, arrest their parents and put them in jail.

Children know whose dads work for police. They are the parents of their classmates, of their friends. Together they study and celebrate birthdays.

***

Children write letters and draw cards to those injured in the violent crackdowns on protests in August, following the presidential election. They draw hearts and write “Thank you.”

Children receive letters from their mothers and fathers, who are in jail for the sole reason of being brave, for demonstrating peacefully. They read letters from prison before bed.

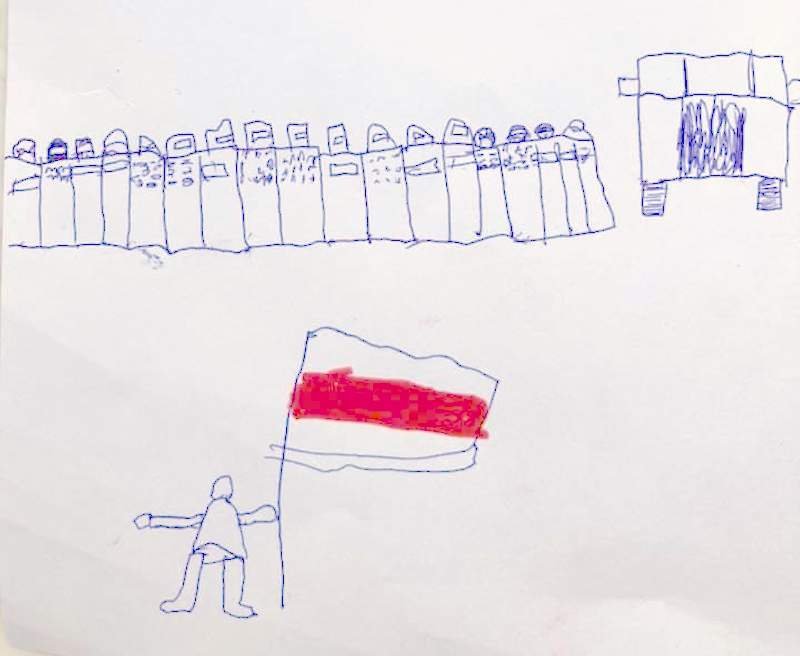

Children play at demonstrations in the street by the house. None of them wants to play the part of riot police: angry people in black clothes chasing peaceful citizens who come out to say no to violence and lies.

At home, children are building a Lego demonstration: many multi-colored figures with white-red-white flags meet the cordon of riot police in black.

Children ask their parents where they go on Sundays. What would happen if both parents were arrested and sent to prison? What is a paddy wagon? What is solitary confinement? Why can’t you walk down the street with white flowers, dressed in white?

Children live and breathe in a constant atmosphere of violence: in their family, kindergarten, school, in their yard, on their street.

Kindergarten, school, and university have become part of the system, part of a dictatorship that wants to produce dull, identical, passive, cruel people who do not ask questions.

The system takes children hostage. The system blackmails parents with an active civil position. The system threatens to take children away from their families. The system organizes inquiries into families where parents have been arrested during peaceful protests. The system prohibits, the system restricts, the system intimidates and blackmails.

The system fears the bright world of free people who have retained their childhood imagination, their critical thinking, responsiveness, empathy, civil engagement, and courage.

The system fears everything that makes people free. The system fears history, music, art, and literature. The system fears everything that is connected with Belarusian identity, the Belarusian language, and Belarusian history.

***

Those who grew up in a dictatorship, in a system built over a span of 26 years, are trying to break out of the system, to break out of the atmosphere of lies, fear and violence.

The children of the dictatorship imagine their own world, they fantasize so as not to be afraid, so as to process their fears in games.

Children read books that make them free. Children read books that create a protective circle around them, an atmosphere of safety.

Children read books that open doors to a different, magical world that does not break them, does not hinder them from preserving their childhood.

Children go out into yards and parks with adults so as not to feel lonely and abandoned. They also want to participate in everything that is happening. In their courtyards, children watch performances, listen to poems, sing songs and dance with their parents.

The children of the dictatorship will carry the trauma of these days through their lives.

We adults can support the children.

We can tell them the truth about what is going on.

We can read them books that neither preach nor moralize.

We can read them books in which a child is a full-fledged participant in the events. Books in which the author treats a child as an equal and does not fear to discuss complex topics.

We can love children, support them, give them hope and protection, and be with them during these difficult times.

The text was written for PENOpp.org’s issue on Belarus, published by Swedish PEN.

Postface

Per Bergström*

Near the Janka Kupala Park in central Minsk there is a statue of the child soldier and war hero Marat Kazei. Children play around the enormous stone fundament, on which the fourteen-year-old Kazei is shown to be throwing a hand grenade, frozen in the moment before he explodes and kills himself and the German enemy. The statue is emblematic of the trauma the Belarusian children have inherited.

But there are people who battle to give the children another kind of narrative. Nadya Kandrusevich-Shidlovskaya is among these. As the translator of Mamma Mu and Pettson, children’s books that depict free thinkers such as The Crow and Findus, as the publishing director of Koska that, apart from Swedish writers such as those mentioned and Emma Adbåge and Sara Lundberg, has also published children’s books by Maryja Martysevich and Dmitry Strotsev.

And even during the recent protests Nadya has worked to create safe havens for the children. She has organized readings and talks and has let the young readers converse with the author Jujja Wieslander (Mamma Mu) on the web. She has helped the children to channel their reactions in drawings and by letting them talk freely about their experiences.

Nadya is also a key person in the cultural exchange between Sweden and Belarus. As an interpreter, for many years, she has moved smoothly amongst people in order to meticulously and unnoticed assist in the communication. If she is asked to step into the limelight as a speaker, she insists instead that the children be allowed to take her place. The children are observing the current events. The children saw the events of the past. Hopefully the children can also envisage a brighter future.

Translated from the Swedish by Christina Cullhed.

*Director and publisher at the Swedish publishing-house Rámus, and artistic director at Malmö International Writer's Stage.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!