On 23 May in Piedmont, Northern Italy, a cable car crashed and killed 14 people. The following morning, on the radio, the former editor of the venerable Corriere della Sera Paolo Mieli suggested a terrorist attack due to some of the victims being of Israeli origin. The suspicion, however, as Mieli himself admitted, was based on nothing.

The episode demonstrates how easy it is, even among those "above suspicion", to slip from level-headed analysis to conspiracy theories which often simplify reality, reassure the audience or play into their sense of identity. It is no surprise that such reorganization of reality proves so effective at a time when, in the West, the great secular or religious ideologies are in crisis and citizens find themselves disoriented. However, in Italy there are also historical specificities driving citizens to dig below the surface.

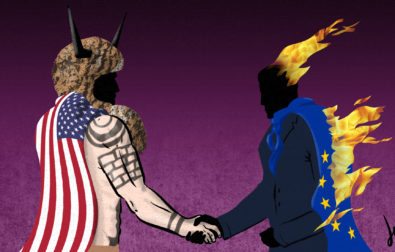

Conspiracy theories and disinformation

- Right in the heart of Europe, a secret and influential disinformation network does Delhi’s dirty work

- A very Italian salsa of populism and conspiracy theories

- QAnon comes to Europe

- A wade through the swamp of Europe’s conspiracy culture

- How George Soros was transformed from herald of democracy into Hungary’s “enemy of the people”

- Andreas Önnerfors: ‘Conspiracy theories are the staple diet of populism in Europe’

Doubt as a tool against the state

In the second half of the twentieth century, doubt has been Italians’ primary tool against the convenient versions of history promulgated by authorities.

This was a period in which the mingling of the Mafia and politics permeated society at various levels; it was also the period which gave us the "Years of Lead": a wave of terrorist attacks, far-right massacres and radical left armed struggles, causing hundreds of deaths and injuries and leaving several serious judicial cases unsolved.

‘I know the names of those responsible […] but I have no proof’

Pierpaolo Pasolini

The facts behind some of these events have subsequently been brought to light thanks to the counter-investigative work of journalists, historians and victims' families. But this work, often confirmed by the Courts, has been hindered or led astray by the state apparatuses all too often found to be involved in those same events.

"I know the names of those responsible [...] but I have no proof," wrote writer and director Pier Paolo Pasolini in 1974 in the Corriere della Sera. Of the counter-investigative work of those decades, the contribution of Pasolini – who was killed a few months after writing those words, in circumstances that have never been fully clarified – is more poetic than concrete. Nevertheless, it still marks the watershed between two eras: the first, where doubt has led to truth, through an evidence-based reconstruction of events that challenges official accounts, and the second, where everyone, as the political scientist Marco Revelli has written, "is a judge of everything. Big Pharma with their vaccines, viruses “that are nothing but a scam to manipulate us”, 5G technology and microchips, Bill Gates and Soros controlling everything, migratory floods driven by the Kalergi plan. Suspicion", Revelli concludes, "has won".

The breeding ground for the current wave of conspiracy theories is, since the early 2000s, often located in the movement gravitating around the comedian and blogger Beppe Grillo, and entrepreneur Gianroberto Casaleggio. From that nebula of influence the Movimento 5 Stelle (5 Star Movement, M5S) was born, a proudly populist political force that rapidly conquered the political stage and entered power.

A map of this sphere has been drafted by centre-left daily La Repubblica. Compared to previously, they argue, "the arguments and political contexts change, but the frame remains the same, bringing water to the mill of Italian populism, whether Lega's sovereignism or the 5 Star Movement: the repeated appeals to freedom of thought and moving against the tide, in order to legitimize attacks on science and expertise, hatred of institutions and the 'mainstream media', and fascination with the Strong Man".

According to La Repubblica, the protagonists of this sphere include fundamentalist Catholics, the so-called Rossobruni [litterally “Red-browns”] nationalist and europhobic russophiles – such as young philosopher "Diego Fusaro, a scholar of Karl Marx but increasingly linked to the far-right," – members of Matteo Salvini's Lega, and "5 Star denialists."

"Anti-vax and conspiracy ideology (from the Trilateral Commission to Big Pharma) has long been promoted by Grillo and Casaleggio through the former’s blog," La Reppublica continues, citing the work of several frequenters of that galaxy, beginning with Claudio Messora. "Messora – writes the newspaper – was M5S’s first head of communications in the Senate: a direct descendant of Casaleggio and now the most impassioned of the online denialists". One of his employees, former reality show participant Rocco Casalino, became the trusty spokesman of Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte (2018-2021).

However, this process does not begin with M5S. We have to go back to the 1990s, when politics was overwhelmed by corruption investigations sweeping through the Christian Democrats and Socialist Party, the main pillars of the ruling majority in the previous decades. The Communist Party, on the other hand, adapting to an ideological seachange, had to deal with a change of name and several splits. In short, all the major popular parties disappeared from the scene. Politics lost every ideological trait and the new political forces identified themselves more and more with the figure of their leader. This opened the door to populism. And it was TV tycoon Silvio Berlusconi who entered, foreshadowing a process that would be replicated around the world.

Enter Berlusconi

It was Berlusconi who, following his grand entrance on the political stage, was the first to proclaim – in the parliament – his role as Prime Minister as directly legitimised by the people and no longer by the Parliament’s vote of confidence, despite Italy being a parliamentary Republic. Subsequently, his adversaries would follow suit. The consequences were dramatic. Parliament almost disappears from the scene. The legislative function is increasingly exercised by the executive by decree, accentuating a process already underway. There are changes in how state powers interact. The republic is de facto presidential, while the political system, now bipolar, openly taps into populist rhetoric.

Moreover, with the relationship between information and power tightening, many Italians turn elsewhere for their news, to an internet still innocent of social networks, as demonstrated by the success of Grillo's blog. Faced with the crisis of established equilibriums, the media and the political system end up adopting closed positions, even in the face of legitimate criticism and opinion. This attitude sharpened feelings of frustration and detachment which would soon be met with open arms.

Enter M5S and the League, fluent in a language that an increasingly lost and angry country wants to hear.

Conspiracy theories, in short, begin to flourish almost as a side effect of populist propaganda, but not as the exclusive result of movements like the League and M5S. On the contrary, all political forces – of both pro-European and sovereignist inspiration, Forza Italia, the party founded by Berlusconi, the Democratic Party (descending from the Communist Party) and Fratelli d'Italia (far-right) – insofar as they are charismatic organizations have contributed to this form of propaganda. Populist rhetoric serves them all in the reconstruction of their identity. And now, any return to reality only seems possible through a kind of politics capable of absorbing the same populist propaganda.

In collaboration with the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Paris

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!