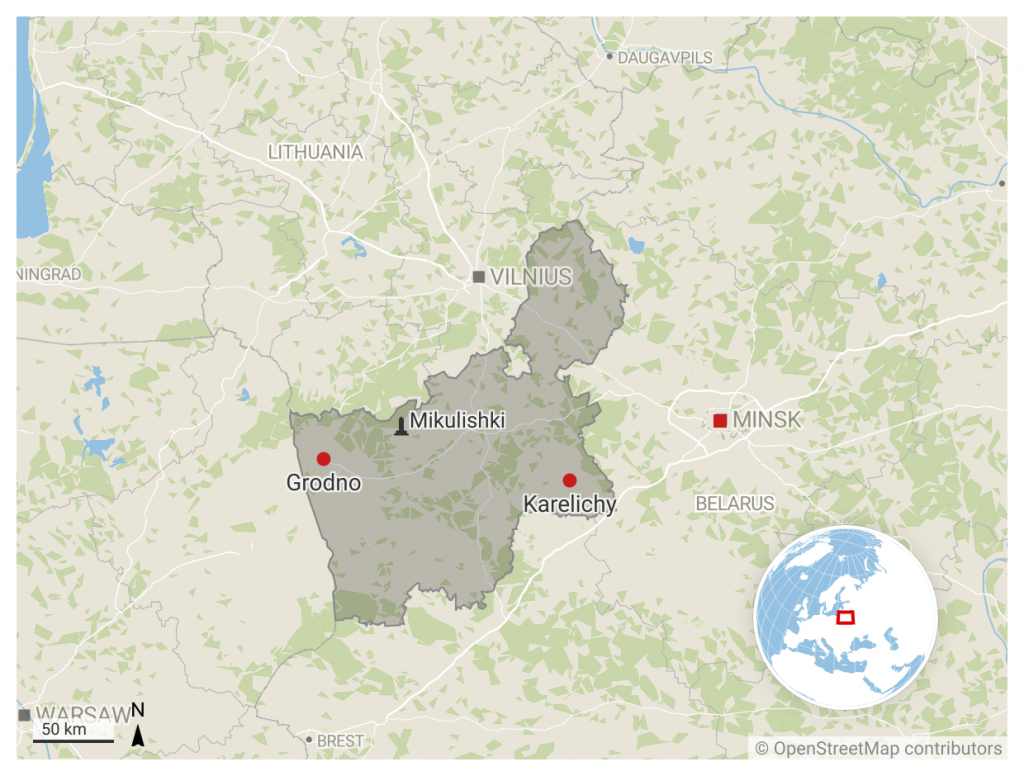

On 27 June, the Union of Poles in Belarus reported that "unknown criminals" had stolen gravestones and dug up the bodies of two Polish soldiers from the AK [Armia Krajowa or Home Army, the WWII Polish resistance]. They died in 1944 in Iodkavichy, near Grodno [formerly a part of Poland].

On 30 June, the Polish foreign ministry claimed that "acts of desecration of places of national Polish memory" had become more frequent in Belarus. According to the Polish diplomats, it mainly concerns the Grodno region, where there are 550 burial sites of the AK fighters.

On 5 July, the Polish Embassy in Belarus published a picture of diplomat Martin Wojciechowski at the place of the destroyed graves in Mikulishki, Grodno region. The press service of the embassy wrote that the Polish military cemetery was "barbarously razed to the ground". Other pictures show traces of tyres. The graves were covered with sand, which was flattened by construction machinery.

The Polish foreign ministry reacted to the destruction of the war graves by summoning the Belarusian chargé d'affaires.

“There were no graves at all”

In response, the Belarusian foreign ministry immediately summoned Martin Wojciechowski. The ambassador was told that there were no burials of foreign soldiers in Mikulishki and "the legality of the works is confirmed by the General Prosecutor's Office and is based on data showing the absence of human remains.”

A couple of days later, a representative of the Union of Poles said that the tombstone at a burial site of the AK fighters in Volkovysk had been destroyed.

And the same day, viewers of "Belsat", a Polish Belarusian-language TV station, learned that the crosses from soldiers' graves had also disappeared near the village of Kachichy, in Korelichy district.

Historian Alexey Bratochkin comments: “The cultural motive [for maintaining such sites] must also be complemented by a political dimension: the will to overcome conflicts and disagreements, including in the area of historical memory. If graves are destroyed, it means we see a challenge not only in relation to culture, but also a political gesture, perhaps an attempt to get revenge not so much for the past as for the present. Namely, the political position of the Polish government in relation to those now in power in Belarus.”

“Gang of Polish nationalists”

In response to the Polish accusations, Belarusian propaganda is formulating its own version of what is happening with the war graves. For example, the newspaper SB Belarus Segodnya, published by the government of President Aliaksandr Lukashenka, quotes political scientist Piotr Petrowski, who suggested that the AK should be recognized as an extremist organisation.

Olga Bondareva, a blogger and activist from Grodno, calls AK fighters "terrorists" on her Telegram channel: “Belarus has blown to smithereens the graveyard of the Polish terrorists from the Armia Krajowa. For those who do not know, the AK is a gang of Polish nationalists, who during the Great Patriotic War cooperated with Germany and engaged in ethnic cleansing of the population of Belarus.”

Aliaksey Bratochkin finds this narrative highly simplistic: “Attitudes to the AK are formed on the basis of what its representatives did in relation to the civilian population, but they also relate to the Nazis, to the question of the borders of Belarus, to the Soviet influence and so on.”

The Armia Krajowa fought both with the Nazis and – depending on the political situation – with the Soviets. The historian Evgeni Mironovich has described the situation in Western Belarus during the Second World War as "a war of all against all". Bratochkin points out that ethnic Belarusians also fought in the ranks of AK.

In 2017, Poland adopted amendments to the "decommunisation law". Within a year 470 sculptural and architectural objects were demolished, most of them dedicated to the Red Army. However, this initiative did not concern war graves.

The debate over socialist-era monuments erupted in February, when Russia invaded Ukraine. On 23 March, the authorities in the village of Chrzowice demolished a five-metre-high stele with a red star, the site of a former cemetery with the graves of 620 Red Army soldiers. Chrzowice was followed by demolition of monuments in the villages of Siedlec, Międzyblące and Garnciarsko.

On 19 April the Belarusian Republican Youth Union held a rally near the Polish consulate in Brest "against the actions of the Polish government to demolish monuments to the Soviet soldier-liberators of the Great Patriotic War".

Polish means guilty

Acts similar to the "law on decommunisation" have been adopted in many countries of Eastern and Central Europe, but the Polish policy of memory is most resented by Belarusian authorities, Bratochkin says: “Of course, there is a common frame of interpretation of World War II - the defeat of Nazi Germany is a beautiful outcome. But the narratives of how the war started, the role of different forces at the time, and the representation of national interests - these differ between Poland and Belarus.”

The official school version of World War II history in Belarus emphasises the Soviet partisan movement, notes Bratochkin: “Different interpretations of events are normal, but there are also conflicts. One of these conflicts is the memory of Romuald Rice's postwar raids on Podlasie and the killing of Belarusians by his soldiers in 1946. Rice was a member of the AK and took part in the anti-Soviet resistance, but also committed crimes against civilians. Belarusian officials have turned this story into one of the key elements of the anti-Polish rhetoric today, as an illustration of a 'genocide of Belarusian people'.”

The Belarusian government has had a number of disputes with Poland over the last two years. One was over the arrest on 25 March 2021 in Grodno of a journalist and activist for the Union of Poles, Andrzej Poczobut. In the view of another Polish journalist, Andrzej Pisalnik: “As Russia carries out "denazification" or de-Ukrainianisation in Ukraine, in Belarus these processes can be called de-Belarusianisation and de-Polonisation. We see it in the context of the military conflict in Ukraine. Belarus is now under Russian occupation. Everything that happens here is initiated by the occupying regime.”

“After the events of 2020, the security forces have turned into historians. History has been declared a zone of national security. The past and its official interpretation should be protected as much as possible, the authorities believe.“

Historian Aliaksey Bratochkin

The historian Aleksei Bratochkin links this campaign to the non-recognition by the Polish government of the official results of the presidential elections in 2020: “The authorities in Belarus under Alexander Lukashenko have always tried to control the loyalty of the national minorities through different mechanisms - on some occasions allowing organisations and schools, for example, and on others prohibiting them. It was a fine balance. But from time to time, the authorities would fight the ‘double loyalty’ of citizens – for example, to criticise the distribution of Polish ID cards, to try to control the activities of the Church in Belarus, to fight grassroots attempts to self-organise, and to control the Union of Poles.”

History written by prosecutors

In spring 2021, Belarus’s prosecutor-general Andrei Shved said that while investigating the criminal case of "genocide of the Belarusian people," police had found "still alive" AK veterans, "who were listed as members of punitive battalions”. Shved said that Belarus intends to ask Poland for "appropriate legal assistance”.

The progress of the investigation has not been reported, but a year later the prosecutor-general was the editor of a book entitled "Genocide of the Belarusian People”. Thus, says Aliaksey Bratochkin, has the prosecutor's office become responsible for historical memory in Belarus: “After the events of 2020, the security forces have turned into historians. History has been declared a zone of national security. The past and its official interpretation should be protected as much as possible, the authorities believe. This explains the laws on genocide of the Belarusian people and against rehabilitation of Nazism, and the amendments to the law on extremism. The proliferation of protest symbols has frightened the authorities. A monopoly on the interpretation of history is being established. This cannot be maintained in a modern society by force. But they are trying to do it today in Belarus.”

Bratockhin believes that the prosecutor’s hopes for a show trial of the AK fighters are unrealistic: “In Europe there are mechanisms for prosecuting crimes against humanity, which have no statute of limitations. But the application of these mechanisms must be justified and individualised. Only those who have committed war crimes can be prosecuted. The Armia Krajowa was not a criminal organisation.”

From 1988 until 1994-95 we had a democratic memory policy. Different groups could participate in public debates about the collective historical past, and thereby influence which versions of history were disseminated.

Now we have a rather rigid official narrative of history, which the authorities are trying to protect by force. But if memory politics becomes democratic once again, then we can have a public discussion about our past together. Then the situation will change for the better.

This story is published within our programme in support of Belarus independent media and journalists.

👉 Original article at The Village Belarus

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!