€110 billion all told, €45 billion thereof this year. The aid package rubber-stamped on 2 May by the eurozone finance ministers to save Greece from bankruptcy was long in coming. It provides "arm’s-length support to dispel the spectre of default and give Greece time to apply a course of shock therapy to its economy”, sums up Libération. But "the eurozone states hardly had any choice in the matter, what with the market panic at the prospect of a Greek default threatening to spread to other countries in the euro area, particularly to the Iberian peninsula.”

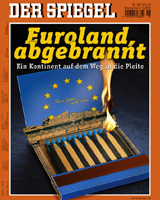

"An epilogue to the Greek crisis is taking shape,” Le Figaro reports with a sigh of relief. The European Union is contributing €80 billion, and the International Monetary Fund €30 billion, to a bailout package “unprecedented in recent financial history”. But “the eurozone got burnt”, opines Der Spiegel on the cover of its latest issue, which pores over the bursting of the “latest bubble”. Greece, it fears, was only the beginning.

The dangers of a policy straitjacket

For some time now, the magazine recounts, the industrialised countries have been living above their means. The financial crisis has swelled national debts to potentially disastrous proportions. Now the bill has arrived for all this past prosperity purchased on the never-never. "Not everyone will be able to pay up,” observes Der Spiegel, painting the worst-case scenario of a financial collapse starting in Athens and dragging Europe and the world down into a crisis worse than the one the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy triggered back in 2008. "Economies the world over are either going to have to go in for some hard-core detox or face a long decline.”

For some time now, the magazine recounts, the industrialised countries have been living above their means. The financial crisis has swelled national debts to potentially disastrous proportions. Now the bill has arrived for all this past prosperity purchased on the never-never. "Not everyone will be able to pay up,” observes Der Spiegel, painting the worst-case scenario of a financial collapse starting in Athens and dragging Europe and the world down into a crisis worse than the one the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy triggered back in 2008. "Economies the world over are either going to have to go in for some hard-core detox or face a long decline.”

Against this backdrop, "is the euro itself in danger? In a word, yes,” says Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman in a New York Times piece reprinted by the Irish Times. Because it remains at the mercy of an inadequate European response to the crisis. “What the crisis really demonstrates, however, is the dangers of putting yourself in a policy straitjacket. When they joined the euro, the governments of Greece, Portugal and Spain denied themselves the ability to do some bad things, like printing too much money; but they also denied themselves the ability to respond flexibly to events. And when crisis strikes, governments need to be able to act. That’s what the architects of the euro forgot, and the rest of us need to remember.”

Germany's melancholy

“If the Greek crisis were a test to find out whether the euro can endure hard times, we’d have to regretfully hand down the verdict: sorry but you flunked, sit down again,” laments the Financial Times Deutschland. The question, explains the financial daily, is “whether Germany, as a major euro country and a pillar of stability, is really putting all its weight behind the euro. Germany needs to change course.” And the government would be well-advised to explain to its citizenry that the euro is a whole lot more than a service that obviates the need to go to the bank before vacationing in Spain.”

To Barbara Spinelli, Germany’s reluctance is due to “a sort of melancholy that threatens to overcome German leaders, a mix of fear of unpopularity, instinctive mistrust of the outside world and a special brand of pride, which induces them to refuse to exercise political leadership in Europe”. La Stampa’s columnist finds that "the history of the double crisis, at once Greek and European, is that of Germany’s difficulties in recovering from that melancholy and the slow, hesitant gestation of a country that accepts the task of leading Europe out of the crisis, starting with a new-found faith in Europe”.

I buy Greek bonds

But now, within the Union, “the big countries have become the bosses again,” headlines NRC Handelsblad. The Dutch daily says the crisis reveals “a new geopolitical reality within the European Union. After a long spell in which the European Commission wielded considerable political influence, it is the member countries that now hold the reins – in other words: the big countries.” And in the current crisis “there is one national government minister at the controls”: German financial minister Wolfgang Schäuble. "He’s hiding behind the IMF and the ECB, but these two organisations are merely working out the technical details of budgetary reforms and restrictions dictated by Schäuble, which the Greeks simply have to accept.”

In this time of prevailing doubts, the Handelsblatt has decided to take action. "As the leading business newspaper in the eurozone, Handelsblatt wants to be the voice of reason,” writes Gabor Steingart, its editor-in-chief. Putting money where its mouth is, the paper is launching an “I buy Greek bonds” campaign, calling on everyone to help Athens by buying Greek bonds (it has already acquired 8,000). "The states can’t save Greece all by themselves. The country can only be successfully stabilised if it can get funds on the market. It’s the banks’ turn now. But it’s also European citizens’ turn to lend their contribution to Athens, to lend it, above all, some trust."

In this time of prevailing doubts, the Handelsblatt has decided to take action. "As the leading business newspaper in the eurozone, Handelsblatt wants to be the voice of reason,” writes Gabor Steingart, its editor-in-chief. Putting money where its mouth is, the paper is launching an “I buy Greek bonds” campaign, calling on everyone to help Athens by buying Greek bonds (it has already acquired 8,000). "The states can’t save Greece all by themselves. The country can only be successfully stabilised if it can get funds on the market. It’s the banks’ turn now. But it’s also European citizens’ turn to lend their contribution to Athens, to lend it, above all, some trust."

From Madrid

European banks exposed

Spanish daily El Mundo reports that the "EU is going to launch the biggest bailout scheme in history to calm down the banking sector". As a matter of fact, much of the €110 billion lent to Greece in exchange for a restructuring plan will be use to repay its creditors, "for the most part European banks”, “which hold two-thirds of the Greek debt”. The Madrid daily points out that the banks concerned are chiefly French (to which Greece owes €56 billion), German (€34 billion) and British (€11 billion). Even Portugal, another country at risk, holds €7.8 billion of the Greek debt. The fact that “one third of Portugal’s debt lies in Spanish hands” constitutes an indirect risk for Spain, which is going to contribute €9.8 billion (12%) to the European bailout package. El Mundo warns in an editorial that if the government fails to take immediate action, “the Spanish economy could find itself in a predicament comparable to that of Greece".

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!