In the nineteenth century, the public’s imagination played a crucial role in the development of national communities in the European continent, as reflected in publications like Benedict Anderson’s Imagined Communities. The theory of this book is that citizens associate with one another at an imaginary level, although they have no personal relationship with one another and pursue entirely different interests of their own.

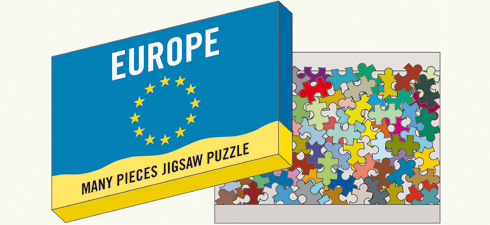

This sort of community spirit has to be conceived, expressed and made tangible. We in Europe, however, have yet to reach this stage. Numerous leaders harp on about the economic benefits of European integration, while steering well clear of any mention of the cultural differences, and rarely point out that the European project also has its intellectual and moral aspects.

It is no easy matter. Europe has a substantial amount of social and cultural differences. I should like to place the spotlight on two particular contrasts. The first is of a horizontal nature, and applies to the Northwest and the Southeast. One of the primary differences is that the former features a high level of secularisation. Many even fear that this may have disastrous consequences for society. When people renounce their faith in God, then the general opinion is that they also care very little about others. The facts, however, paint an entirely different picture. Voluntary work, for example, is the most highly developed in countries like Sweden, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom.

High trust societies

Another difference is that citizens in the Northwest more often feel involved in public matters. They take a greater interest in politics and are given more opportunity to speak their minds or exercise some sort of influence. Furthermore, all manner of social, cultural and recreational ventures are launched there, while it also has a highly developed civil society.

It is not without good reason that nations in this region are referred to as high trust societies. The fact that businesses, citizens and other actors have a certain amount of confidence in one another, certainly contributes to economic development. The modern, secularised, wealthy and democratic society, which values professionalism, vitality and human dignity, is more profound in the Northwest than in the South and East.

Apart from the horizontal divide, however, there is also a vertical one. Take the question of whether people have faith in the European Union for instance. This is closely linked to people’s education. Only 37 percent of people who left school before the age of fifteen have confidence in the EU, while the percentage among students on the other hand is a hefty 63.

The same picture arises if we pose the question of people’s attitude to the further expansion of the European Union. Almost half the respondents are firmly against such expansion. Once again, however, this attitude is much more common among people with a limited education (51 percent) than among those currently studying (29 percent).

Those citizens who feel somehow threatened by processes of modernisation are generally inclined to adopt a less optimistic attitude, which also applies to the issue of Europe. If the European project is to develop any further, then it is essential that these two divides be bridged.

Opinions and sensitivities

In the case of “horizontal” dialogue, I propose that a genuine exchange be set up between ordinary people with their roots in the North and South, and the West and East of our continent. The aim should be to allow people to become acquainted with one another’s way of life, for instance by spending a year in the opposite region of Europe. In the process, particularly close attention could then be devoted to the manner in which opinions and sensitivities, values and ideals, traditions and ambitions have an effect on people’s daily lives.

The second dialogue that I would applaud concerns the vertical divide. At present there is still a world of difference in how the prosperous and highly educated elite view the European project and the increasing uncertainty being felt by the masses of less well-educated citizens. This divide cannot simply be bridged by an information campaign or a sophisticated communication strategy. If you want people to embrace the notion of Europe, then you have to take the experiences and expectations, the values and concerns of ordinary people into account.

Involvement and human dignity

Such a dialogue will only be successful if leaders those in public office develop a new habitus. A large group of citizens feel abandoned by modern administrative elites who do not excel in empathy or social involvement, with a view of the world that is both liberal and harsh at the same time.

Is such a dialogue possible? I believe that the cultural dynamics that have ultimately led to modern life contain a number of philosophical principles, which are shared - whether consciously or not - by countless Europeans. Keywords like freedom, fairness, equality, autonomy, involvement and human dignity come to mind. While the dialogue should also deal with how we realise these principles in practice, the very fact that such a discussion is taking place also implies that we no longer regard European integration as an ‘irreversible process’.

After all, history is a dialectical process. Those in power have a say, but so do their peoples. So whoever tries to impose the European project as an imperative shouldn't be surprised with the growing support given to eurosceptic political parties like the SP and the PVV.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!