Chapter 4

In previous chapters, we revealed how Michelin and the stakeholders of the Tropical Landscapes Finance Facility (TLFF) – the platform that issued the green bonds used by Michelin and its Indonesian partner Barito Pacific to finance the development of their rubber plantations (see chapters 1, 2 and 3) – concealed and then downplayed the ecological devastation caused by Royal Lestari Utama (RLU). RLU had cleared the forest just before the French company became a minority shareholder in late 2014. (Barito then held 51% of the property, which was eventually bought out in summer 2022 by Michelin.)

👉 Read chapter 1: European green finance is paying for deforestation in Indonesia: the case of Michelin

👉 Read chapter 2: How a project decried for its environmental impact became a flagship of European green finance

👉 Read chapter 3: How Michelin and its Indonesian partner sidestepped the rules for green bonds

Both the opinions of environmental experts and the documents that Voxeurop has consulted lead to the same conclusion: the land that was turned into rubber plantations before Michelin acquired its stake in RLU should have been preserved. It was part of the large forest ecosystem of Bukit Tigapuluh, or "Thirty Hills".

The destruction of this habitat renders Michelin’s and Barito's project non-compliant with the international standards that the two partners committed to when they used green bonds to finance it. In reality, Barito's enterprise started long before the two actors formalised their collaboration at the end of 2014 (see Chapter 3).

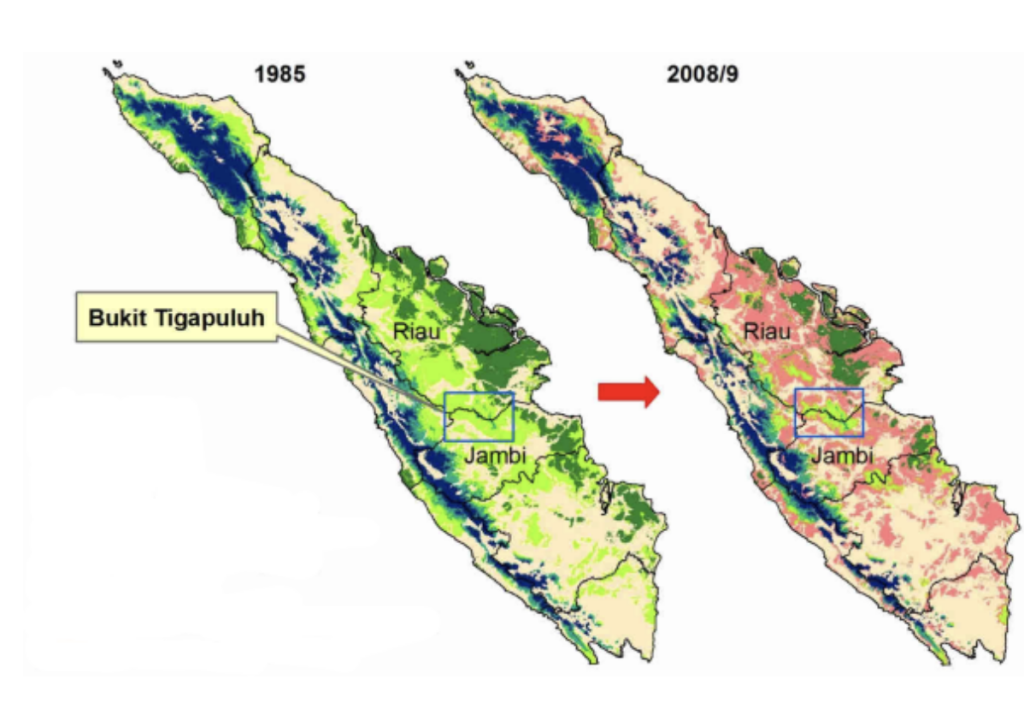

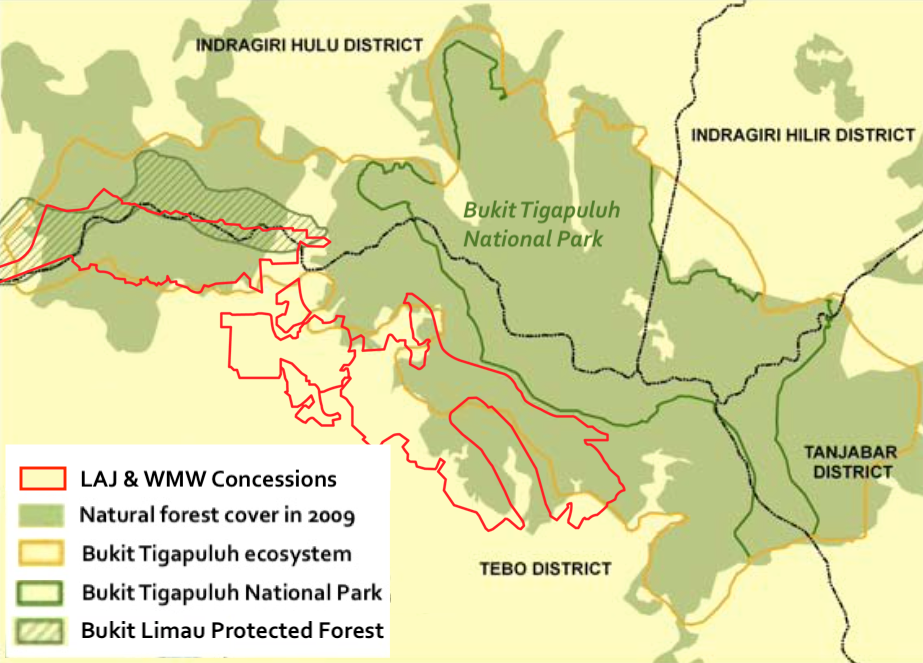

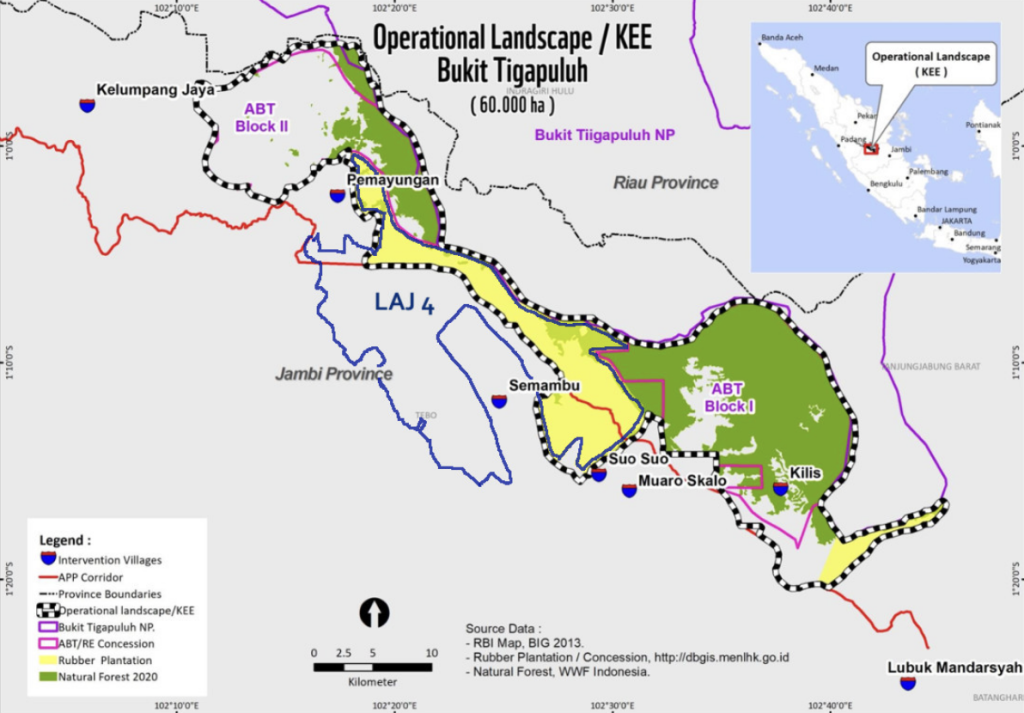

Straddling the provinces of Jambi and Riau (the most deforested in Sumatra), the green expanse of Bukit Tigapuluh includes the national park of the same name, established in 1995, as well as the surrounding forests – or at least what remains of them today. At the time that Lestari Asri Jaya (LAJ), a local subsidiary of RLU, obtained its clearing permit in Jambi, these forests made up almost half of the Bukit ecosystem. As of 2010, the total forest cover was 320,000 hectares (20% of which falls within the current LAJ concession). This was already only half of the 622,000 recorded in 1985, according to a 2010 report co-authored by several NGOs, including the Indonesian branch of WWF.

Primary or secondary forests: a crucial issue of definition

Barito Pacific thus managed to deal a major blow to the primary forests of this region in an entirely legal manner – by taking advantage of the lax regulatory framework in Indonesia. According to the scientific understanding, primary forests are defined as woodland that has not been completely cleared and then regrown, regardless of whether it has been altered by human intervention in some way.

In contrast, by Indonesian law, as well as by the definition of the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO), primary forest is interpreted more narrowly. (1) In this view, even forests that have been slightly degraded by selective logging (harvesting of a small amount of timber – as distinct from clearcutting, where the majority of trees are felled) – fall into the category of secondary forest.

Unlike primary forests, secondary ones are not protected by the moratorium on deforestation, which was only adopted in 2011 by the then Indonesian President Bambang Susilo Yudhoyono (and extended by him and his successors since). (2)

"In Indonesia, a company can apply for a permit to selectively log a primary forest, which the government then has the option of re-labelling as secondary before granting a clearing licence, so logging companies – such as LAJ – can formally claim not to log primary forests," Matthew Hansen told Voxeurop. A remote-sensing researcher in the Department of Geographic Sciences at the University of Maryland, he has helped develop the world's largest database and most robust methodology on primary-forest loss. The process described by Hansen is precisely the one that Barito would have used. (3)

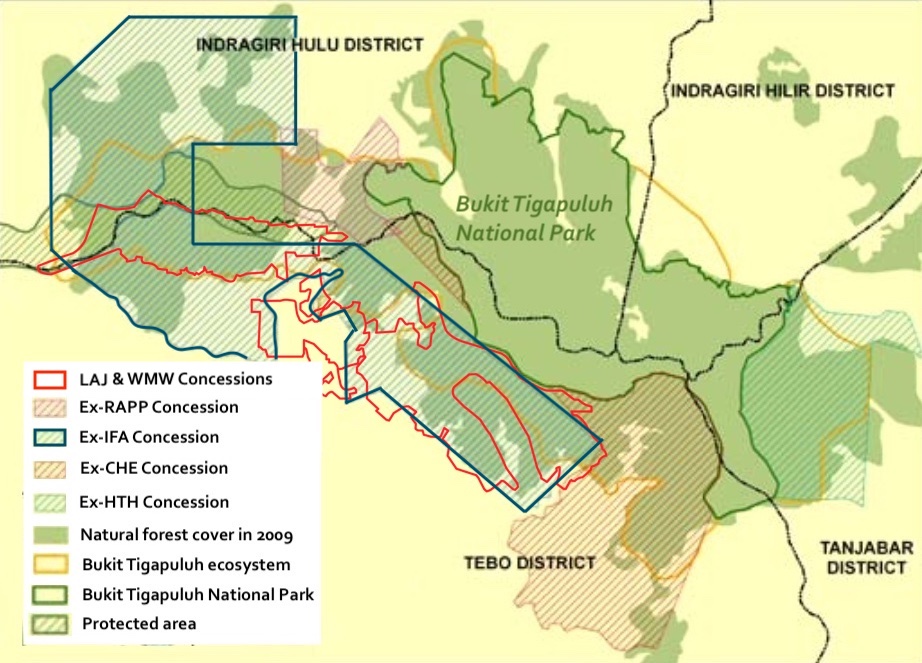

Prior to giving the green light to the clearing by LAJ and other similar companies, the Indonesian environment ministry only allowed selective logging in the Bukit Tigapuluh forest ecosystem. This was in the 1990s, when much of the local forest was still classified as primary. The largest selective logging company active in the area was Asian Forest Industries (IFA), also owned by the Barito Pacific group, as discovered by Voxeurop. Barito Pacific owned IFA through its subsidiary in the name of Barito Pacific Lumber, as evidenced by a notarial deed from 2020 unearthed by Voxeurop.

Once it expired at the turn of the century, its concession of about 300,000 hectares was gradually split into multiple concessions for intensive exploitation (allowing the conversion of forests into agricultural production). Among them was the 62,000-hectare plot granted to LAJ in 2010. The forested part of this parcel was "de-classified as secondary forest in 2008", explained Johan Kieft, Secretary General of TLFF and UNEP's senior specialist on land use and the green economy, to Voxeurop. Kieft thus implicitly confirms that LAJ brought back to Barito 20% of the former IFA area – which was situated in a portion that had until recently been categorised as primary forest. And along with it came the right to clear the land.

This background is noted in the 2010 NGO report mentioned above. It cites a 2005 field study by local NGO KKI Warsi and Bogor Agricultural University, which concluded that the native forests in the former IFA concession, although selectively logged, still retained a volume of wood with a high carbon-storage potential and that it would therefore make more sense to restore them than to convert them to plantations. (4)

"Primary forests that are selectively logged and therefore legally categorised as secondary" – such as those that were permanently cleared by LAJ – "still have the capacity to provide important biodiversity and carbon sinks", Hansen concurs.

"Degraded forests can recover naturally or through assisted restoration, and eventually return to their primary-forest state," echoes the FAO Forestry Department.

"Our analyses show that before being allocated to LAJ, the area had dense natural forest with old growth trees, although it was not completely intact and may not have qualified as primary under Indonesian rules," said Elizabeth Goldberg, head of Global Forest Watch (GFW). She cites an interactive map tracking the loss of primary forests worldwide since 2001, regardless of whether they have been downgraded by national laws.

Locals in the deforested areas confirm what the satellite observations and interactive maps tell us. For example, Sumbasri, a farmer who has lived since 1975 in the village of Pemayungan, which is now located right in front of RLU's rubber plantations, told Tempo reporters that "before LAJ's clearing, there was still a forest, although not a very dense one, since the biggest trees had been cut down by IFA before".

The TFT/Earthworm audit report commissioned by Michelin (see Chapter 2) concluded that clearcutting in the concession had also affected areas of high biodiversity alongside the Bukit Tigapuluh National Park, that should have been protected.

The reliability of the environmental impact assessment approved by the Jakarta government in 2009, which would have allowed Lestari Asri Jaya to destroy valuable but degraded ecosystems, is implicitly questioned even by Michelin's public affairs director. "We found a valuable forest where [according to LAJ's logging plan] there should only be bushes to clear. We had to change the plans to protect these places," Hervé Deguine told Voxeurop, referring to the period following the signing of the joint venture with Barito Pacific, before which Michelin could only passively watch the industrial deforestation.

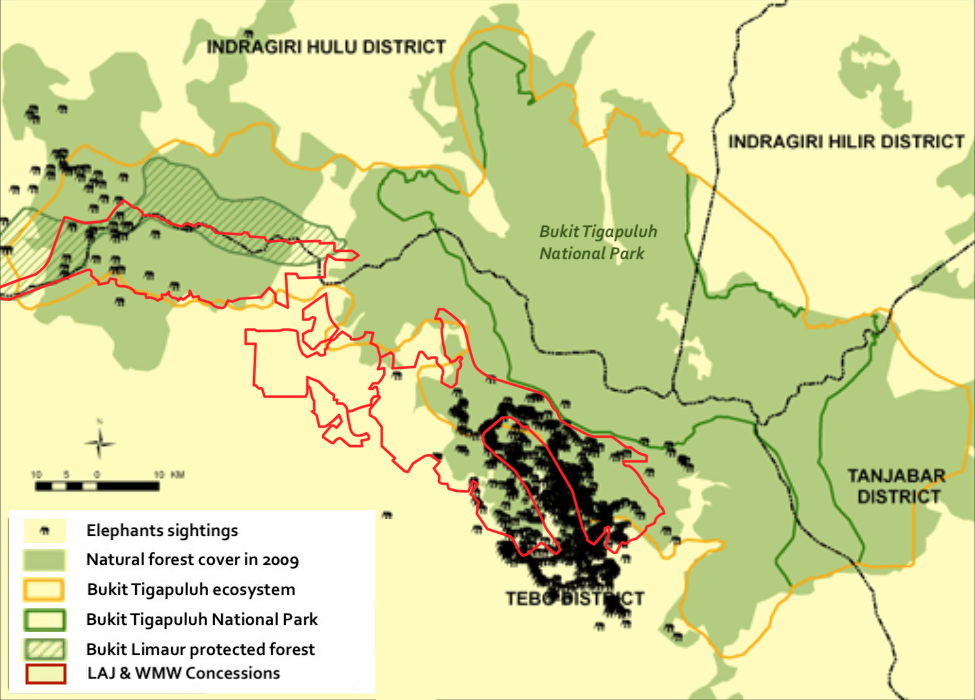

Furthermore, the Indonesian government itself recognised in 2007 in its conservation plans (5) that protecting habitats such as Bukit Tigapuluh was crucial to saving animals at high risk of extinction, such as the tiger, elephant and Sumatran orangutan. All three are listed in the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Critically Endangered Species and have suffered unabated declines in Sumatra, according to figures cited in a recent study by Bogor Agricultural University.

These mammals prefer to live in the lowland rainforest, which is less protected because it is outside the national parks. Often mountainous, like Bukit Tigapuluh, these parks are more difficult for the animals to access.

In 2008, the National Park Office and the Indonesian Nature Conservation Agency (BKSDA) had agreed to the delineation proposed by the NGOs (including the Indonesian branch of WWF) to expand the protected forest area from the 143,223 hectares of the national park to a total of 348,084 hectares including the surrounding forests. In 2009 an implementation plan, developed by the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS), was agreed by NGOs (such as WWF) and local governments. It was also officially approved by the Directorate General for Natural Resources and Ecosystem Conservation of Indonesia’s environment ministry. For their part, the NGOs involved insisted that the government revoke the commercial licences in the area to be protected (including those resulting from the split of the IFA area, including LAJ).

However, despite its commitments, even at the international level, the Indonesian government gave in to economic interests. The area that should have been called "Bukit Tigapuluh Ecosystem" never saw the light of day and was instead largely left to the clearcutters.

Bukit Tigapuluh Ecosystem: an expansion of the national park of the same name to the surrounding forests, as indicated in a plan endorsed by the Indonesian authorities in 2009. It included the areas that would subsequently be included in the concessions of LAJ and WMW in 2010. | Source: Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and the Directorate General of Natural Resources and Ecosystem Conservation of the Indonesian Ministry of Environment and Forestry

Contrary to the mantra posted in response to Mighty Earth's critical report, Royal Lestari itself finally acknowledged in its 2020 sustainability report that the LAJ concession incorporates "an essential ecosystem [...] where wildlife roam[s]" freely. It finally promised to manage the area sustainably in collaboration with the BKSDA and the National Park Board (10 years after the NGOs' request). It is a pity that this acknowledgement of the facts comes only after the destruction, and replacement with rubber plantations, of almost all the forest that bordered the Bukit Tigapuluh Park.

For Alex Wijeratna, campaign director of environmental NGO Mighty Earth, "It seems RLU was defining the same contiguous forest area as either ‘degraded’ or ‘essential’ depending on whether the aim was to convince investors that the part cleared was not worth protecting or to persuade them that protecting the remaining trees was worth their money."

Yet the ecosystem was always an integrated whole, both before and after the joint venture and the bond issue. This is confirmed by the UNEP Atlas of Globally Important Biodiversity Areas, hosted on the Global Forest Watch platform. The atlas includes the declining Jambi forest as one of the last refuges for animals on the IUCN Red List of threatened species.

Chetan Kumar, senior programme coordinator at IUCN, told Voxeurop that IUCN's policy "focuses on protecting primary forests, but also on the need to prevent the loss, and ensure the restoration, of degraded forests that can provide habitats for specific species, such as elephants in Sumatra."

Rubber plantations where elephants roamed

Together with the Bukit Tigapuluh National Park, the northeastern boundary of the Lestari Asri Jaya concession forms a homogenous landscape of high biodiversity. The park is home to a large population of elephants, as well as tigers – it is one of the Global Priority Landscapes for their conservation – and orangutans. The latter have been introduced through a programme that has covered much of Sumatra since 2001, mainly in the Bukit Tigapuluh ecosystem.

"The secondary forest that LAJ cleared was part of the core habitat of elephants and other large mammals because of its very high food density," said a conservation expert who witnessed the clearing operations and who wished to remain anonymous.

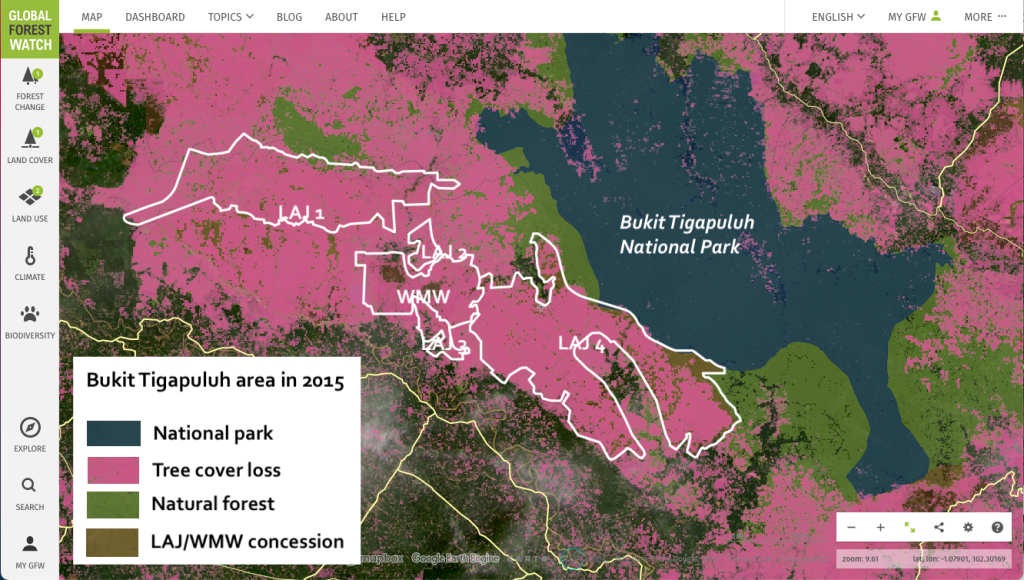

RLU/LAJ specifically targeted the forest in the portion of the LAJ concession known as Block 4, located at the southeastern end of the concession, on the edge of the national park.

"Block 4 of the LAJ concession [see map below], in particular, is a vital corridor for elephants, where these animals come to feed by transiting between conservation areas outside the company's concession," said our anonymous conservation source. As a link between the national park and the two concessions, this area plays an important role in restoring the ecosystem – one that WWF managed from 2015-2020, before it ended its relationship with RLU (see Chapter 1). "Elephants use this passage because they can't go around either from the north, where the park is very steep, or from the south, where they would be in densely populated areas."

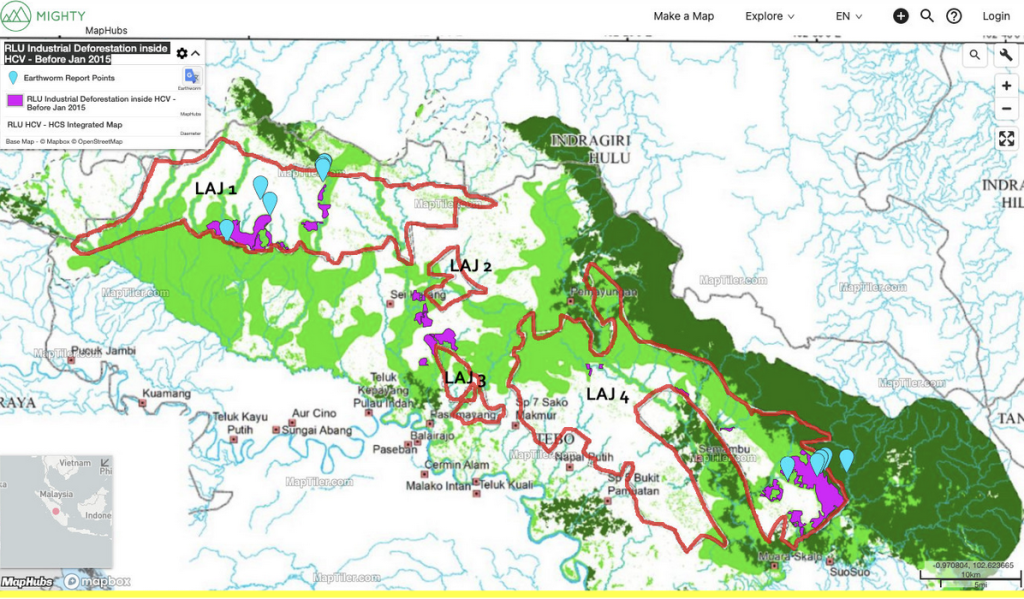

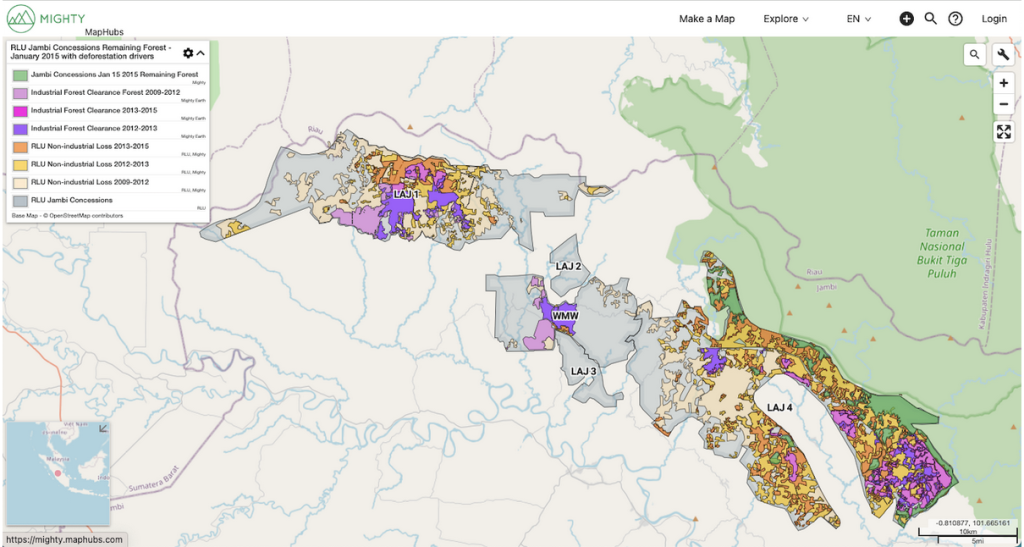

According to calculations by Leo Bottrill, managing director of geospatial technology company MapHubs, the elephant ecosystem on the fringes of the national park lost 2,590 hectares of trees (out of a total of 3,232 in Block 4) between April 2012 and January 2015 due to forest clearance. The majority (59%) of the rubber trees already planted in the LAJ concession when Michelin officially intervened in early 2015 (see Chapter 1) were in this area.

Bottrill estimates that RLU also cleared 3,852 hectares in Block 1 of the same concession, on the edge of the Limau Protected Area (in the northwest corner of what should have been the Bukit Tigapuluh Ecosystem), and 1,384 hectares in the small WMW concession.

Local conservation activists told Voxeurop, on condition of anonymity, how things seem to have unfolded on the ground. In their view, Royal Lestari Utama neglected the protection of elephant habitat and surreptitiously pursued its routine agribusiness, even after Michelin joined the group. Their account breaks the omerta that RLU has imposed, via confidentiality clauses, on the NGOs involved in the various conservation programmes in Jambi. These include WWF, the Frankfurt Zoological Society (FZS) and the Forum Konservasi Gajah Indonesia (FKGI). Together they had fought unsuccessfully for the creation of the large Bukit Tigapuluh Protected Area that was agreed – on paper – with the Indonesian authorities in 2009.

Since the meeting on land-use planning at the Ministry of Environment and Forestry in November 2010, and in follow-up interactions with LAJ (which had now obtained its clearing permit), these NGOs submitted several studies, supported by data from the BKSDA. This information showed the importance of the remaining forest and shrubland within the concession, not only for elephants, but also for tigers and orangutans.

LAJ initially promised that most of the secondary forest in Block 4 would be kept intact or selectively logged and then allowed to regrow. But before long, the conversion of wildlife habitat to rubber monocultures began. In 2013, elephants and other animals began to be driven off the plantations in Block 4, increasing human-wildlife conflicts in the surrounding villages and smallholder farmlands.

Royal Lestari also indirectly contributed to further deforestation and loss of biodiversity in the region by facilitating non-industrial clearing (by illegal loggers). In order to extract the logged trees, roads were built through previously remote forest areas to the Bukit Tigapuluh National Park. According to the Mighty Earth report, old tracks were upgraded and over 100km of new roads were built between April 2012 and 2015.

This opened up access to farmers as well as to poachers and illegal loggers (mostly “immigrant” land speculators from other parts of Indonesia). They infiltrated not only the LAJ concession itself, but also the adjacent forest areas, which are virtually unmonitored by the company's security guards. Non-industrial deforestation, equivalent to 30,000 hectares (more than 70% of the concession's 42,000 hectare forest area in 2009), has thus progressed in parallel with the industrial sort (20% of the area), as Leo Bottrill's cartographic timeline shows.

Industrial deforestation by RLU and non-industrial deforestation by illegal loggers in the LAJ concession peaked in the period between the granting of the clearing permit in 2010 and the joint venture between Barito and Michelin that resulted in their respective non-deforestation policies. | Source: Nusantara Atlas, Greenpeace Indonesia, TLFF

In an email to Mighty Earth quoted in the NGO's 2020 report, Michelin downplayed the impact of RLU's activities, saying that deforestation by locals should be attributed solely to the "permit to open a road corridor [...] in the [LAJ 4] area" (6), which the government granted to the neighbouring Sinar Mas Group's Asia Pulp & Paper (APP) company.

Michelin failed to mention, however, that LAJ itself made use of this same road, as indicated in a report co-authored by WWF and local NGO KKI WARSI. It used the road to transport timber that had been harvested since 2010 from its own concession – after clearcutting the trees for rubber plantations, LAJ/RLU sold the timber to local sawmills. Its customers also included APP's own pulp mills, according to a letter signed by several local NGOs.

In their 2010 report mentioned above, the NGOs denounced the 82-km road that APP had started building through Bukit Tigapuluh National Park in July 2007 – illegally (the environmental impact assessment would be approved only a few months later). The road was built expressly to transport timber to its pulp mills from its partners' concessions, including the LAJ concession (which was to receive a government logging permit shortly thereafter).

"When they got the concession, LAJ/RLU were making money mainly from selling high-value timber, so they needed to clear the forest," says Alex Wijeratna of Mighty Earth. "It was only when Michelin met with them and advised them that they began to seriously consider setting up a rubber business," he concludes.

Thus RLU/LAJ was able to kill two birds with one stone: it sold the trees cut in its concession and planted rubber trees on the cleared land. The deforestation only stopped after the joint venture between Barito Pacific and Michelin was signed and their respective non-deforestation policies were published. That was always going to be too late to protect them from suspicion of greenwashing.

End of chapter 4

In the next part of the investigation, we will look at Michelin's entry into the game in 2015. It did not contribute, as promised, to improving the environmental situation. Nor did it make good the damage to wildlife and local people wrought by its partner's wholesale deforestation.

Notes

1) The FAO defines primary forest as "a naturally regenerated forest of native tree species, where there are no clearly visible signs of human activities and where ecological processes are not significantly disturbed".

2) The moratorium on deforestation was prolonged until 2015 and made permanent in 2019.

3) A study by the University of Maryland found that more than 90% of Indonesia's primary forests were eventually completely razed after being degraded by initial human intervention, such as selective logging. These forests were considered secondary by the authorities in Jakarta and were not protected. As a result, the country had only reported half of its primary forest loss to the FAO by 2015.

4) Darusman, D., Bahruni, Siswoyo & Trison, S. (2006) Final Report: Valuation of Forest Resources in Area of ex PT. Industries et Forest Asiatique (IFA), West part of Bukit Tigapuluh National Park. Cooperation between KKI Warsi & Laboratory of Forest Policy, Economic and Social Faculty of Forestry, Bogor Agricultural University.

5) Departemen Kehutanan (2007) Strategi dan Rencana Aksi Konservasi Harimau Sumatera (Panthera tigris sumatrae) 2007-2017. Departemen Kehutanan (2007) Strategi dan Rencana Aksi Konservasi Orangutan Indonesia 2007-2017. Departemen Kehutanan (2007) Strategi dan Rencana Aksi Konservasi Gajah Sumatera dan Gajah Kalimantan 2007-2017.

6) Email from Hervé Deguine, Michelin Public Affairs Director, to Mighty Earth on 7 July 2020.

👉 Glossary and abbreviations

👉 Read chapter 1: European green finance is paying for deforestation in Indonesia: the case of Michelin

👉 Read chapter 2: How a project decried for its environmental impact became a flagship of European green finance

👉 Read chapter 3: How Michelin and its Indonesian partner sidestepped the rules for green bonds

Field work in Indonesia conducted by our media partner Tempo was supported by a grant from the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized Crime. The investigation was also supported by the Environmental Reporting Collective, Journalismfund.eu and Mediabridge.

With the support of Investigative Journalism for Europe

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!