“Greece should never have been admitted into the eurozone.” Less than three weeks before the September 22 elections, Angela Merkel rolled out the heavy artillery on August 28. The German Chancellor has every chance of being re-elected. Her party, the Christian Democratic Union (CDU), is expected to pick up from 39 to 42 percent of the votes, against 22 to 25 for the Social Democratic Party (SPD) of her rival Peer Steinbrück.

Some polls even give her a cumulative 47 percent by adding the votes for her current partner, the liberal party (FDP), which would allow the coalition to govern together for four more years. In reality, the strong language of the CDU candidate reflects a new nervousness in the German election campaign, which has been distinguished so far by its monotony.

In stigmatising Greece, the front-runner is attacking not only former Chancellor Schröder of the SPD, whom she accuses of having let Athens into the eurozone in 2001; after all, as she recalled during the televised duel on Sunday evening, the SPD has supported all the plans to bail out Greece that were brought to Parliament for a vote. The other opponent Angela Merkel is attacking is none other than the new Eurosceptic party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

Credited with three percent in the opinion polls, the outfit that was formed in the spring is one of the biggest unknowns of the September 22 election. However, since finance minister Wolfgang Schäuble reopened the debate on Greece by declaring in late August that there “still must be an aid plan” for the country in crisis, the new party is enjoying an unexpected context to promote its flagship project: the splitting up of the eurozone into northern and southern zones.

Underestimated AfD

[[Pollsters are beginning to recognise that the AfD could get a higher vote than the opinion polls are currently suggesting]]. Allensbach estimates that eight percent of voters are not ruling out voting for this party, led by an economics professor. “The electoral potential of AfD has been underestimated,” says Bettina Munimus, Professor of Political Science at the University of Kassel. “The party is a haven for all the conservative voters disappointed by the CDU and its European policy.”

A key element behind her assertion: the demography. Of 62 million people eligible to vote, one-third, or more than 20 million, are retirees. According to the Foundation for the Market Economy, “the 2013 election should be the last election for decades in which the majority of voters will be under the age of 55.”

With the galloping aging of Germany’s population, the “democracy of retirees” evoked in 2008 by the former president of the Republic, Roman Herzog, is no longer a myth, but a reality. While a growing margin of retirees are suffering from more difficult living conditions, the traditional CDU voter is less concerned. That voter worked hard up until retirement and remembers the three post-war decades of growth associated with the strong deutschmark.

The conservative retiree, reader of the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung or Die Welt, will be more sensitive to the theses of the AfD, which have found a wide echo in these newspapers. Namely, that the euro crisis and the bailout of countries like Greece represent for him a double threat: one to his savings, plagued by low interest rates, and the other to the public finances, which pay his pension but will also have to foot the bill for bailouts to countries in crisis.

Getting the grey vote

The AfD, whose campaign rallies are well-attended by voters with greying hair, is the ideal outlet for these conservatives – especially if they are also disappointed by the swing to the left taken by the CDU under the presidency of Angela Merkel. The abolishing of military service, the phasing out of nuclear power, and the introduction of a minimum wage that the Chancellor now proposes: many are the decisions and projects that break with the liberal and Catholic roots of the party of Konrad Adenauer. The AfD, which also advocates a stricter line on immigration, mainly caters to those who are no longer following the new line, without however appealing to the electorate on the left, or even the far left. “To vote for the new party is a way for these people to express their protest,” says Bettina Munimus.

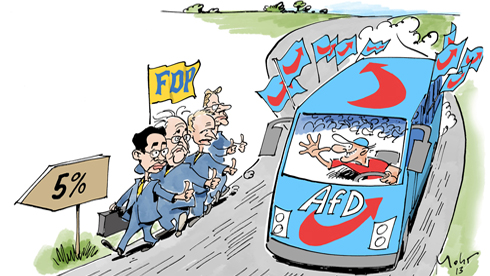

The German electoral system, moreover, favours such a vote because the voter has two ballots to cast: one for the candidate in his constituency in the Bundestag, and the other for the party. In 2009, many conservative voters cast their first ballot for the candidate of the CDU but their second for the Liberals, as a protest against the swing to the left taken by Angela Merkel. The FDP was thus able to register a historic result, capturing more than 14 percent of the votes.

If the Eurosceptic party gets over the five percent threshold that allows it to enter the Bundestag – which would be a major surprise – the task of Angela Merkel will be made more complicated. If she is unable to form a majority with the FDP, the Chancellor will be forced to govern with the SPD in a grand coalition, as happened between 2005 and 2009. But even the AfD does collect only between three and five percent of the votes, the CDU will face new competition on its right, which could have a significant impact on its European policy.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!