Stylia Kampani did everything right, and she still doesn’t know what the future holds for her. The 23-year-old studied international relations in her native Greece and spent a year at the University of Bremen in northern Germany. She completed an internship at the foreign ministry in Athens and worked for the Greek Embassy in Berlin. Now she is doing an unpaid internship with the prestigious Athens daily newspaper Kathimerini. And what happens after that? “Good question”, says Kampani. “I don’t know.”

“None of my friends believes that we have a future or will be able to live a normal life,” says Kampani. “That wasn't quite the case four years ago.”

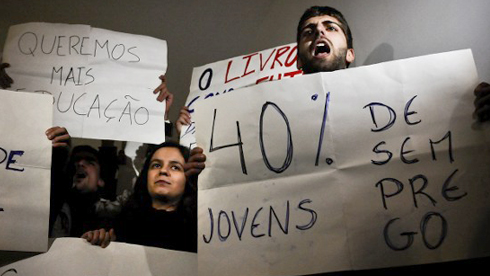

Four years ago -- that was before the euro crisis began. Since then, the Greek government has approved a series of austerity programs, which have been especially hard on young people. The unemployment rate among Greeks under 25 has been above 50 per cent for months. The situation is similarly dramatic in Spain, Portugal and Italy. According to Eurostat, the European Union’s statistics office, the rate of unemployment among young adults in the EU has climbed to 23.5 percent. A lost generation is taking shape in Europe. And European governments seem clueless when they hear the things people like Athenian university graduate Alexandros are saying: “We don't want to leave Greece, but the constant uncertainty makes us tired and depressed.”

Instead of launching effective education and training programs to prepare Southern European youth for a professional life after the crisis, the Continent’s political elites preferred to wage old ideological battles. There were growing calls for traditional economic stimulus programs at the European Commission in Brussels. The governments of debt-ridden countries paid more attention to the status quo of their primarily older voters. Meanwhile, the creditor nations in the north were opposed to anything that could cost money.

In this way, Europe wasted valuable time, at least until governments were shaken early this month by news of a very worrisome record: Unemployment among 15- to 24-year-olds has climbed above 60 per cent in Greece.

Suddenly Europe is scrambling to address the problem. Youth unemployment will top the agenda of a summit of European leaders in June. And Italy’s new prime minister, Enrico Letta, is demanding that the fight against youth unemployment become an “obsession” for the EU.

Big promises, scant results

These are strong words coming out of Europe’s capitals today, but they have not been followed by any action to date.

For instance, in February, the European Council voted to set aside an additional €6bn to fight youth unemployment by 2020, tying the package to a highly symbolic job guarantee. But because member states are still arguing over how the money should be spent, the package can’t begin earlier than 2014.

A recent Franco-German effort remains equally nebulous. Berlin and Paris want to encourage employers in Southern Europe to hire and train young people by providing them with loans from the European Investment Bank (EIB). The concept is supposed to be unveiled at the end of May. German labour minister Ursula von der Leyen is its strongest advocate.

In contrast, German efforts to combat the crisis have been limited to recruiting skilled workers from Greece, Spain and Portugal. But now politicians are realising that high unemployment in Athens and Madrid is a threat to democracy and could be the kiss of death for the eurozone. Perhaps it takes reaching a certain age to recognize the problem. “We need a program to eliminate youth unemployment in Southern Europe. [European Commission President José Manuel] Barroso has failed to do so,” says former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, now 94. “This is a scandal beyond compare.”

Economists also argue that it’s about time Europe did something about the problem. “The long-term prospects of young people in the crisis-ridden countries are extremely grim. This increases the risk of radicalisation of an entire generation,” warns Joachim Möller, director of Germany’s Institute of Employment Research, a labour market think tank.

The Franco-German proposal to help Southern European employers is a case in point. Under the plan, the €6bn from the EU youth assistance program would be distributed to companies through the EIB and thus would multiply, as if by magic. In the end, speculate the plan’s proponents, 10 times as much money could be brought into circulation, putting an end to the credit crunch facing many Southern European small businesses.

As it is, there are doubts over the usefulness of broad injections of cash. The first measures coming from Brussels were ineffective and came to nothing. Last year, the European Commission promised the crisis-stricken countries that they could use unspent money from structural funds to implement projects to provide jobs to unemployed youth. Some €16bn had been applied for by the beginning of this year, funds intended to benefit 780,000 young people. But the experiences are sobering, and concrete successes are few and far between.

An alternative solution?

According to a draft of a position paper the German cabinet intends to discuss in June, Germany wants to support the crisis-stricken countries in “incorporating elements of dual vocational education and training into their respective systems”. The government intends to set up a new “Central Office for International Educational Cooperation” at the Federal Institute for Vocational Education and Training, which could send advisors to the crisis-stricken countries when needed. Ten new positions have already been approved for the new office.

The key to combating youth unemployment is to reform the divided labour market. But as an internal report by the German government shows, the crisis-stricken countries have hardly made any progress on this front. According to the report, Portugal potentially has “additional efficiency reserves in its school system”, while Greece is showing only a few signs of progress, such as a plan to “assist young unemployed women”.

The problems associated with a divided labour market are especially striking in Italy, where older workers with employment contracts that are practically non-terminable hold onto jobs, making them inaccessible to younger workers. The words on a demonstrator’s T-shirt in Naples summed up the mood among young people: “I don't want to die of uncertainty.”

In Athens, young university graduate Stylia Kampani is now thinking of starting over. She is considering moving to Germany. And this time, she adds, she might stay there.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!