The Franco-German partnership has played an enormous role in shaping and uniting postwar Europe. The two countries have generally been stronger on European integration – creating a common market and currency, the Euro – than in war and diplomacy. However, with the crisis in Ukraine, Paris and Berlin have made the European Union (EU) into a trade bloc with a bite, imposing significant sanctions on Russia.

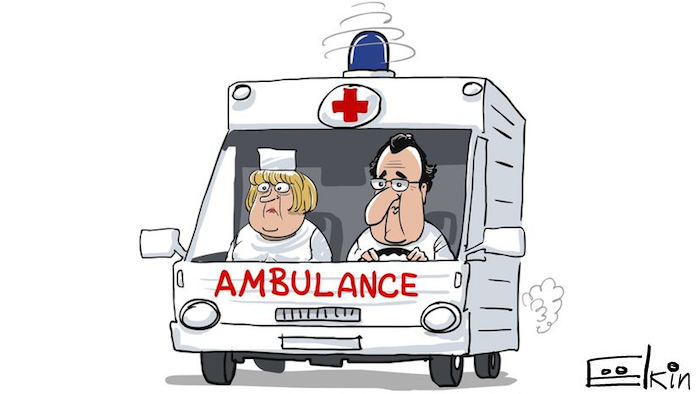

At the same time, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President François Hollande have taken a largely reactive approach, providing little long-term leadership to turn the EU into a true strategic power in line with its economic clout.

In terms of foreign policy France and Germany are typically out of sync. There are deep-rooted asymmetries: While Germany is still largely a civilian power uninterested in foreign interventions, France takes pride in her atom bombs and numerous military expeditions in Africa.

A trade bloc with bite

In that respect, one can see significant progress as Paris and Berlin have taken a much more assertive role in shaping the European response to Russia, especially in the wake of the crisis and civil war in Ukraine. The EU considers Russia’s unilateral annexation of Crimea and support for eastern Ukrainian secessionists as unacceptable behavior in the post-Cold War order.

The EU has been able to impose significant sanctions against Russia, including cutting off major Russian companies from European financial markets, banning exports of advanced mining and exploration equipment for the critical Russian oil and gas sector, and various restrictions on specific individuals.

European sanctions have not, however, achieved their maximal objectives in Ukraine: The end of the eastern insurgency and the dislodging of Russia from Crimea. This is not surprising. Put simply: Moscow will always care more about Ukraine than Brussels.

Chancellor Merkel and President Hollande have been taking the lead in meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin and mediating with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. The Franco-German couple has had some success in promoting limited ceasefires, but ultimately the conflict smolders on. Crimea seems to be irreversibly split from Ukraine and eastern Ukraine looks headed to become a “frozen conflict” similar to Transnistria in Moldova or South Ossetia in Georgia.

Towards a European Army?

Paris and Berlin can thus claim to have made significant progress in making the EU into a “power” relative to Russia. But one has to say that, more generally, Chancellor Merkel and President Hollande have shown little leadership in making Europe into a genuine strategic actor.

The problem is that of the sovereign: National capitals decide whether to commit to an EU mission, there is no “European decider.” National governments prefer to cling to their armies both as a good in itself and as a bargaining chip to be primarily used in a NATO context. This allows lesser European leaders to hobnob with American officials, potentially tapping into or influencing Washington’s massive military, diplomatic and surveillance power.

There is certainly pressure for change. According to one Eurobarometer poll some 46 percent of EU citizens support in principle the creation of a European Army. Educated Europeans are increasingly “European” in outlook with the spread of English and the internationalization of culture through American TV shows, film and music, through business and education.

But the pressure for Europeanization is too often negative. National governments – typically in Southern and Eastern Europe – are perceived as so corrupt that alienated young people imagine a European government would be preferable. Any fundamental changes in the EU’s strategic power – such as a European Army or the imposition of sanctions by majority instead of unanimity – would require a change to the European Treaties towards radical federalism.

Such a federalization would be particularly difficult for the French government to sell, where European integration is often blamed, by both mainstream and radical politicians, for hard choices and often unpopular reforms. As the Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Sustainable Governance Indicators (SGI) point out, “The result is that these concepts are regularly accused of destroying the basis of society and the hallowed ‘French way of life.’”

Any “leap of integration” is unthinkable so long as euroscepticism is rising on the back of the euro crisis and as so many national governments remain unpopular. A durable economic recovery and redressing of public opinion are necessary, before any eventual changes. As the French might say, l’Europe puissance n’est pas pour demain.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!