The greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression (1929-1939) has produced a crisis of democratic legitimacy not unlike the one that fuelled the rise of fascism in the interwar years. During the postwar era (1945-1989) collective memories of total war—as well as the economic success of liberal democracy—ensured that neo-fascist movements remained politically marginal. However, the Great Recession (2007-13) has reinvigorated the far right as a viable political alternative. Reflecting on the present moment, China Miéville notes: ‘There has not in living memory been a better time to be a fascist. We live in a utopia: it just isn’t ours.’

Today’s neo-fascist movements in western Europe have built on the rhetoric of their predecessors in speaking of ‘taking back control’, ensuring that ‘our white race … continues to exist’ and fighting ‘an invasion of foreigners’. These political resonances, combined with similarities in structural conditions to the 1930s—a financial crisis followed by an economic collapse, leading to poverty, high unemployment and mass migration—have led to warnings of a ‘return of fascism’ and worries that we are living through a ‘new Weimar era’.

In an earlier post I focused on the role of migration and forgetting in the rise of ‘illiberal democracy’ in east-central Europe. Similar dynamics of forgetting are also present in the western part of the continent. In contrast to explanations of right-wing authoritarian populism which focus on economic or cultural factors, I argue that generational change and the loss of memory of total war in western Europe play a crucial role in the current crisis. It is not a coincidence that the populist renaissance has occurred seven decades after the end of the second world war.

Memory and integration

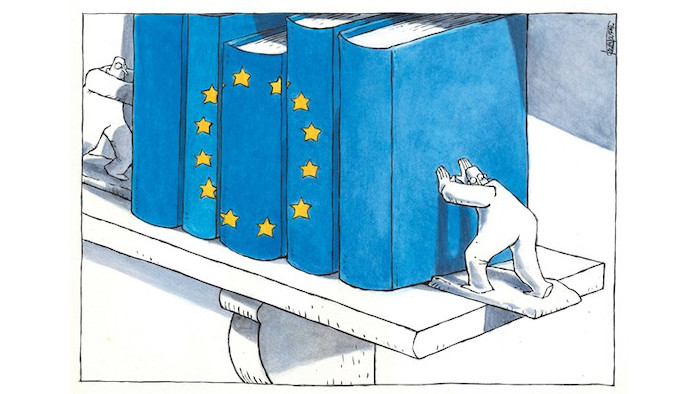

In the aftermath of two world wars and the Holocaust, ‘never again’ was more than just a slogan: it was an imperative for political change. References to collective memories of these events played a crucial role in justifying the pooling of sovereignty through European integration. The lessons of total war also inspired the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, as well as the creation of the Council of Europe—and hence the European Court of Human Rights and the other institutions which anchored the protection of fundamental rights in postwar European and international law.

The individuals who initiated these organisations came from the generation that had lived through Europe’s age of total war (1914-45) as adults. This cohort was followed by the ‘forty-fivers’, who came of age during the war and thus bore no responsibility for it. They questioned the actions of their parents and the intellectual traditions of their homelands in order to come to terms with the legacy of 1945. The leaders of this generation deepened integration through the completion of the common market, the opening of intra-European borders with the Schengen agreement, the creation of the euro and the empowerment of the European Parliament.

With the turn of the second millennium the leadership of Europe has passed to a cohort with no memory of the second world war. As the generations which experienced the war have begun to pass away, so have the broader normative demands of memory they carried. Rather than a push for further integration, within this first cohort of individuals who have no personal experience of total war one finds a concentration of support for neo-fascist, authoritarian populists. The nostalgia underpinning the rise of this movement is rooted in this generation’s own memories of a better, supposedly easier life within purportedly independent nation-states during the height of western Europe’s Wirtschaftswunder (‘economic miracle’) of the trente glorieuses (the ‘glorious 30’ years from 1946 to 1975).

Yet this perception of the economically independent, politically sovereign ‘nation’ requires nation-states to ‘be imagined into periods when in fact they did not exist’. While the postwar ‘baby-boomers’ remember the national state as the locus of economic prosperity, this image is partial at best. The economic, political and social integration of the continent was already well under way during this period, even if this was not always immediately obvious in the everyday experiences of individuals.

In fact, far from moving from empire to nation to integration over the course of the postwar period, as many Eurosceptics seem to believe, western Europe underwent a transition directly from colonialism to economic integration after 1945. The false narrative of the postwar economic boom as the heyday of the sovereign state, which Timothy Snyder refers to as ‘the fable of the wise nation’, combined with the loss of personal memories of war and suffering, poses a profound challenge to the values and institutions which previous guarded against the renewal of fascism.

Defending democracy beyond the state

Awareness of the importance of generational change and the loss of European memory in fuelling the rise of the far right is crucial for the present day. The lesson of the 1930s is that liberal democracy — a regime which protects economic, social, political and civil rights in a ‘co-original’ or ‘equi-primordial’ manner—cannot be preserved or developed via the nation-state alone. On the contrary, international institutions play a crucial role in ensuring that the potentially jingoistic general will expressed within nation-states does not trample on the rights of minorities or political dissent.

Democracy is about more than just elections and majority rule: it is about preserving the plurality of opinions as well as the respect for the rights of individuals and minoritiesnecessary to make elections and majoritarian decision-making meaningful. The history of the 20th century shows that the ‘will of the people’ can only function properly within constrained democracies which work together to protect fundamental human rights.

An international framework for liberal democracy was the central goal of the global order created in the aftermath of the second world war. In the face of the return of fascism as a realistic political alternative to mainstream politics in western Europe, these international institutions are essential to constrain nationalistic notions of popular sovereignty—now more than ever.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!