“Yevgeny Matveev, mayor of the city of Dniprorudne in the region of Zaporizhzhia, was captured at the start of the invasion because he refused to cooperate with the Russian military. He was tortured and finally killed in captivity. At least his body has been returned”. Nataliia Yashchuk is the Senior War Consequences Officer at the Centre for Civil Liberties, a Ukrainian human rights organisation and winner of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize. She rattles off a long list of names and information about civilians and military personnel who have ended up in captivity in Russia and the occupied territories, including Crimea.

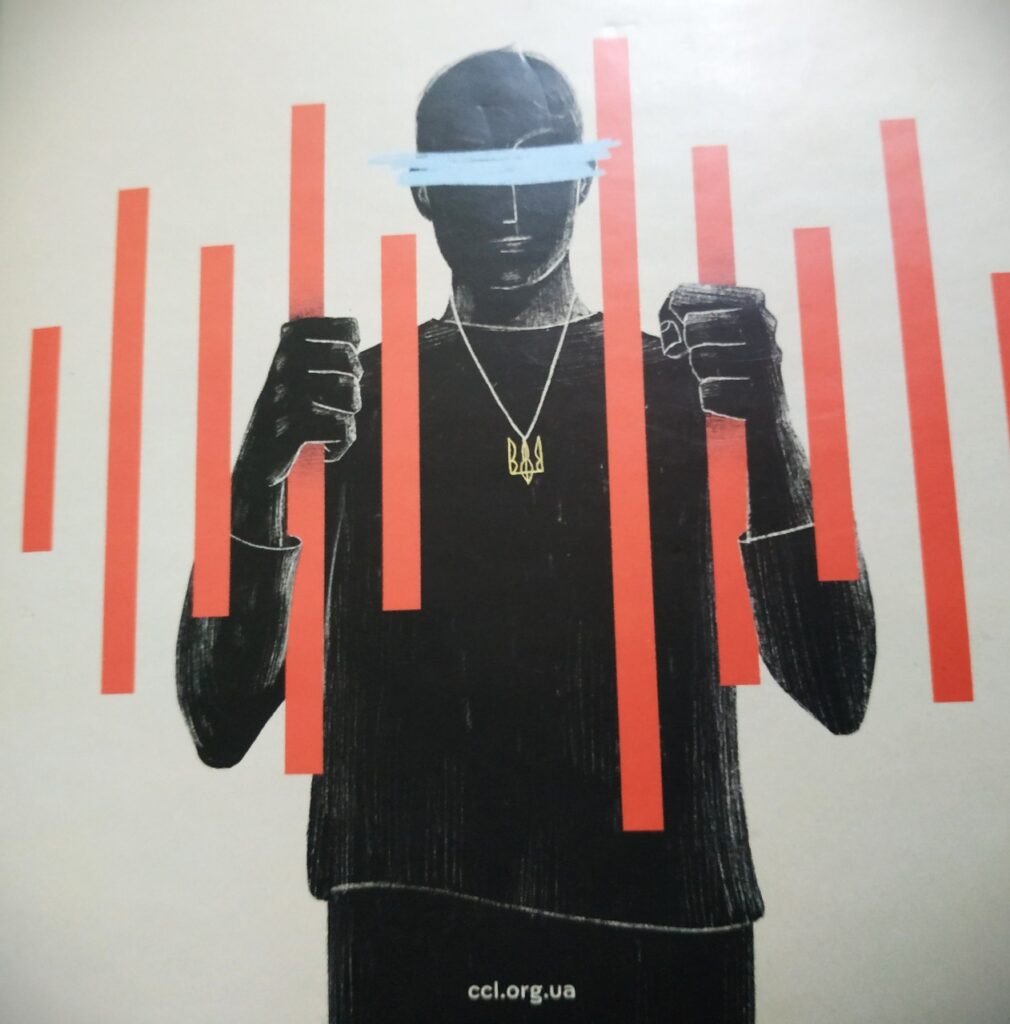

“Then there are entire families,” says Nataliia, pointing to photographs in a 2023 booklet entitled Prisoner's Voice. “A person with permanent disabilities, a student, a workman, a computer scientist who fled the occupation in Crimea, a man who tried to save his wife, who died in his arms. Stories of all kinds. Andriy, Mykola, Serhiy…”

“Women too?” I ask timidly. “Women too. Iryna Horobtsova, a volunteer from Kherson: they took her away in front of her parents, kept her in solitary confinement, without documents or information for over a year. And then they built a fake case against her, and convicted her, according to their laws, as a spy”.

These are just some of the stories that have come to the attention of Yashchuk and the humanitarian workers who, like her, are involved in human rights in one of the most active associations in Ukraine. Most cases of imprisonment, explains Yashchuk, occur in the occupied territories, where it is estimated that around 16,000 people are illegally detained.

But the figures are approximate, as are those for children abducted and deported. The latest cases involve families torn apart, civilians interrogated, detained, tortured and then perhaps released; others are transferred to unknown locations and, after one or two years in captivity, convicted on trumped-up charges.

In addition to military personnel, there are civilian prisoners, citizens who live (or lived) in regions controlled by the Kyiv government, more or less far from the front line: Sumy, Chernihiv, Kharkiv, Kherson, Zaporizhzhia. But they also come from the region of Kyiv. “In the Kyiv oblast alone, in a month and a half of occupation, they kidnapped about 500 people,” adds Yashchuk, who, together with colleagues and volunteers, continues the search – the search for prisoners, but also for justice”.

“This is the most documented war in human history,” says Oleksandra Matviichuk, director of the Centre for Civil Liberties. “We have in our database, which we are conducting together with partners, more than 88,000 episodes of war crimes. These are not just numbers. Behind these numbers are specific human destinies”.

The nuances of political detention: civilians vs military personnel

In the current context of the Russian war in Ukraine, civilians and military personnel are detained in the same conditions, often together, without any distinction. However, it is important to understand that they are not exactly part of the same category of political prisoners, which is essentially based on the legal and institutional status of the person at the time of detention, as well as the context in which the deprivation of liberty occurs (in the case of civilians, these may be journalists, activists or demonstrators; and in the case of military personnel, these are members of the armed forces, security forces or paramilitary forces).

This is something that the Russians themselves, the jailers, tend to confuse, though in this case the confusion is deliberate.

“They are clearly all people who have been captured, directly or indirectly, in more or less complex situations,” explains Yashchuk. “The most difficult situation concerns those who are arrested in the occupied areas and then held for long periods without clear reason, often on serious and unjustified charges. This also applies to some military prisoners, who are subjected to particularly harsh conditions. For convenience or simplification, we talk about ‘prisoners of war’ when referring to those who have been captured. But this term really only applies to military personnel. Civilians cannot be considered prisoners of war because they are not combatants. These civilians are victims of kidnapping, arbitrary detention, unfounded legal persecution and other abuses”.

Knowledge of the situations faced by civilians is usually very limited. Although some human rights organisations are working on their behalf, the scale of the problem remains largely invisible. In Ukraine, the Association of Relatives of Political Prisoners of the Kremlin is an organisation that seeks to shed light on the issue, together with organisations such as the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group (KHPG).

“There are two related reasons why civilians are not released,” explains Maksym Kolesnikov, a former prisoner of war who has served in the Ukrainian armed forces since 2015. “Firstly, because it would be tantamount to admitting a crime. Secondly, they are reluctant to draw fresh attention to these crimes”. Originally from Donetsk, Kolesnikov was captured on 20 March 2022 during the battle of Kyiv. After ten months in captivity, he was released in a prisoner exchange in February 2023. According to his testimony, there were over 500 detainees, both civilians and military personnel.

“At first they took us to Belarus, to a filtration camp, for about two days. From there, we were taken to the city of Novozybkov, in the Russian region of Bryansk, to a preventive detention centre. The Russians pass off Ukrainian civilians as military personnel: the Russian army simply makes them wear Ukrainian armed forces uniforms”, explains Kolesnikov, recalling that, according to the rules of war, civilians should not be captured because they are not military personnel, and this violates international conventions.

The testimonies of those who return from Russian captivity

Physical and psychological trauma, difficulties in returning to “normal” life (if we can call it that in a country at war) and a lack of systematic support from the state: these are the challenges and obstacles faced by those who have endured Russian prisons, confinement in dark basements or cellars, and often violence and torture. What awaits a person after release and what do they need, physically, emotionally and legally? What role can society, communities and volunteers play?

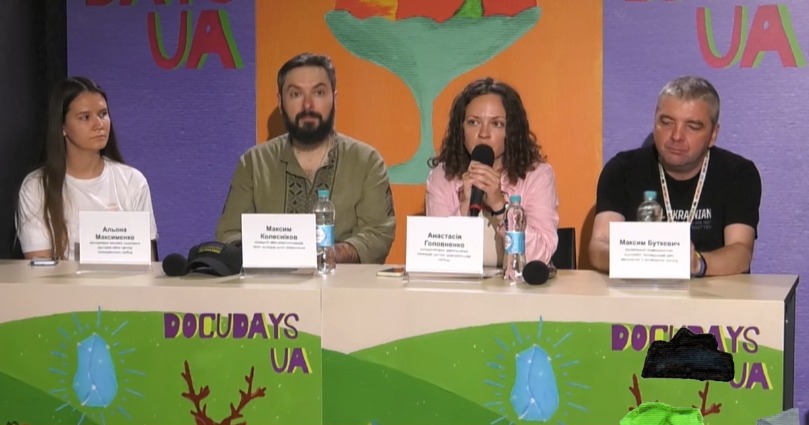

Kolesnikov and Maksym Butkevych, a Ukrainian human rights defender, journalist and civil society activist released from Russian captivity in October 2024, sought to answer these questions during one of the meetings on human rights at the Docudays documentary film festival.

“Combined medical and psychological support is essential,” says Butkevych, after stating that the initial reintegration he underwent for four weeks in a rehabilitation centre for military personnel was very important for him. A co-founder of the ZMINA Centre for Human Rights and Hromadske Radio, Butkevych enlisted as a volunteer in the Ukrainian armed forces in early March 2022. In July of the same year, he was captured by the Russian army and sentenced to 13 years in prison on trumped-up charges. He was released in a prisoner of war exchange in October 2024.

‘Civilians cannot be considered prisoners of war because they are not combatants. These civilians are victims of kidnapping, arbitrary detention, unfounded legal persecution and other abuses’ — Natalia Yashchuk

The most difficult part of rehabilitation, according to Butkevych and Kolesnikov, is psychological assistance, especially given that many people believe they do not need it. In addition, some also need social and legal assistance, especially if they come from occupied territories and have effectively lost everything. “My rehabilitation lasted about three weeks: identification of problems, medical examination, tests, psychological tests,” explains Kolesnikov, who had lost 32 kilos in captivity.

When it comes to rehabilitation and reintegration, while there is a well-defined protocol for the military, there is no such thing for civilians. “But it needs to be created!” insists Yashchuk. “Prosecutors and investigators must record the crimes committed and act in accordance with the Istanbul Convention. All this must be done by specialists, by experts. And we have them. But we are well aware that, given the current numbers and the numbers when more return, we will not have enough. The system needs to be strengthened”.

There are non-governmental organisations, foundations and religious organisations that are helping. One of the goals achieved within Ukraine is the amendment of legislation so that civilians who have been released are protected and cannot be mobilised. This is no small achievement.

“However, here too, a deep and structural problem emerges,” explains Yashchuk. “We are talking about people who come mainly from the occupied areas. Their stories are very different: some managed to escape, some managed to pay a ransom for a family member, some were released in less formal ways. But there is one common element: they suffer all kinds of violence until they are psychologically broken. And when they are completely ‘destroyed’, if their captors need to obtain something – a business, a home, a vehicle, any asset – they find a way to make them sign documents or give up everything they have in exchange for the promise of freedom. That person, now deprived of everything, often makes the difficult decision to return to Ukrainian-controlled territory. And here a new ordeal begins: they cannot prove that they were imprisoned, tortured or illegally detained. They have no evidence, no official records, nothing to prove their experience because their name does not even appear on the “blacklists”. And those who could testify to this remain in the occupied areas. Thus, a vicious circle is created, and the state does not yet have a clear, effective procedure for recognising these invisible victims. This is a gap that we must fill. Because until there is a system that recognises and protects these people, justice will remain incomplete, and the return to freedom will only be partial”.

The European line on repatriated political prisoners

Alona Maksymenko, a colleague of Natalia Yashchuk, has helped highlight the solutions needed for the successful reintegration of people returning from captivity. First and foremost, immediate access to care and assistance: implementing and monitoring programmes that include medical and psychological assistance, document acquisition and financial support, with a particular focus on families.

However, this must be done transparently and within the framework of clear laws and procedures. Some guidelines have been set out in the law on reintegration, adopted on 15 March 2024, which should ensure a stable system to support the release and rights of freed prisoners.

Government authorities and institutions (ministries, commissions, government organisations) should work in perfect harmony with civil society, each filling in the gaps to provide economic, legal and social assistance.

A further step should be taken by seeking international support. Since the illegal annexation of Crimea in 2014, the European Union has imposed economic and legal sanctions to put pressure on Russia in the context of the conflict with Ukraine (18 packages of sanctions have been adopted so far, the latest in July 2025).

These are undoubtedly key instruments aimed at bringing the Russian economy to its knees and recognising its crime of aggression. In this regard, the creation of a Special Tribunal for the Crime of Aggression against Ukraine, announced in 2023 and supported politically and financially by Brussels, aims to fill a gap left by the International Criminal Court, which cannot prosecute Moscow for the crime of aggression due to jurisdictional limitations (Russia is not a signatory of the Rome Statute). The tribunal is expected to be established by the end of 2025 and will be tasked with judging the Russian political and military elite held responsible for the war, reinforcing the no-impunity principle even for leaders of powerful states.

According to Oleksandra Matviichuk, such an institution is necessary, and constitutes a political decision in the broadest sense: “If we want to prevent wars in the future, we must punish the states and their leaders who start these wars now. And this sounds like common sense. But there has been only one such precedent in the entire history of mankind: the Nuremberg and Tokyo Tribunals. [...] But remind that the Nuremberg Tribunal is a court of the victors. That is, it tried Nazi war criminals after their regime had fallen. And as sad as it may be, such an unspoken norm was set that justice is the privilege of the victors. But justice is not a privilege. Justice is a basic human right”.

Although it does not directly affect the fate of Ukrainian prisoners currently detained in Russia, this legal instrument is an essential first step in building a future framework of international justice and accountability.

Indeed, while Brussels has taken action against Moscow in this regard – albeit with limited results so far due to systemic evasion, diversification towards non-aligned partners and internal weakness in implementation – it is also true that the actual impact of European initiatives supporting Kyiv, aimed in particular at the issue of repatriated political prisoners, which is rarely discussed outside Ukraine: at present, there are no centralised, structured programmes guaranteeing direct access to psychological or socio-economic support for those returning from captivity. In the absence of such programmes, access to these measures remains largely managed by Ukrainian national actors, NGOs and humanitarian agencies, rather than by direct EU programmes.

Indeed, while Brussels has taken action against Moscow in this regard – albeit with limited results to date due to systemic evasion, diversification toward non-aligned partners, and internal weaknesses in enforcement – it is also true that the actual impact of European initiatives supporting Kyiv, particularly on the issue of repatriated political prisoners, remains unclear. This issue receives little attention even outside Ukraine. Currently, there are no centralized, structured programs ensuring direct access to psychological or socio-economic support for those returning from captivity. In the absence of such measures, access to support is largely managed by Ukrainian national actors, NGOs, and humanitarian agencies rather than direct EU programmes.

Political prisoners in Crimea

The Centre for Civil Liberties, together with other organisations, also deals with Ukrainian political prisoners in Crimea, particularly Crimean Tatars. “Currently, there are more than 200 cases related to Crimea, where citizens are convicted for political reasons. In addition, they also persecute the lawyers of Crimean Tatars, depriving them of their licences so that they cannot defend their own people in Crimea”.

One of the most important and high-profile cases is that of two lawyers, Lili Hemedži and Rustem Kamiljev, who had their licences revoked and were then raided and subjected to intimidation. Their battle still continues to this day. They are not allowed to work or represent the interests of Crimean Tatars. They are constantly persecuted.

The most notorious case of political imprisonment in Crimea is that of Nariman Dzhelyal, a journalist and political activist born in Navoiy, in the former Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic, who returned to Crimea with his parents in 1989. A contributor to the ATR television channel and the Avdet newspaper, since 2013 he has been the first vice-president of the Mejlis, the representative body of the Crimean Tatar people, and head of the Information and Analysis Unit. He was arrested on 4 September 2021 for the alleged “sabotage of a gas pipeline in Crimea, in the village of Perevalne”, and charged under Article 281, paragraph 2, of the Russian Criminal Code, which carries a prison sentence of between 10 and 20 years.

Unlike those of his colleagues, family and friends, Dzhelyal’s story has a happy ending. On 28 June 2024, Dzhelyal managed to return to Ukraine and last May was appointed by the Ukrainian president as ambassador to Turkey.

Prisoners in oblivion

The situation of Ukrainian political prisoners, both civilian and military, remains dire: tens of thousands of citizens are detained in Russia and in the occupied territories, often without any legal recognition, accused of trumped-up charges such as terrorism or espionage and subjected to systematic torture in extreme detention centres such as Taganrog. The tragic death of Ukrainian journalist Victoria Roshchyna in a Russian prison is testimony to the brutality of Moscow’s repressive system.

Denouncing these war crimes, securing the release of all political prisoners and providing concrete assistance to them and their families is, to say the least, necessary. This can be achieved by keeping national and international attention focused on their situation and pushing the European Union to establish concrete, targeted and coordinated support programmes. Indeed, despite declarations of political support and funds allocated to Ukraine, the EU’s role in the issue of Ukrainian political prisoners remains marginal and poorly structured.

Brussels should consider unanimously and more actively promoting the creation of an international monitoring mechanism on detention conditions, supporting reintegration and rehabilitation programmes for returned prisoners with dedicated funds, and pushing for the introduction and implementation of targeted sanctions against Russian officials involved in arbitrary detentions. Furthermore, a coordinated EU diplomatic initiative could help strengthen multilateral pressure on Russia to ensure respect for human rights. Countries such as Poland and the Netherlands, which are among the main promoters of European resolutions on the recognition of Russian responsibility for war crimes, illustrate how a sustained commitment, both at national and European level, can foster the development of essential instruments.

When it comes to the issue of such prisoners, the European political agenda needs to be more concrete and visible, and not merely symbolic.

🤝 This article was produced thanks to Thematic Networks by Pulse, a European initiative supporting transnational journalistic collaborations, with the collaboration of Francesca Barca (Voxeurop) and Maryna Svitlychna (OBC Transeuropa). The interview with Oleksandra Matvijčuk was conducted on 16 July during the Ukraine Recovery Conference 2025 in Rome by Maryna Svitlychna.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!