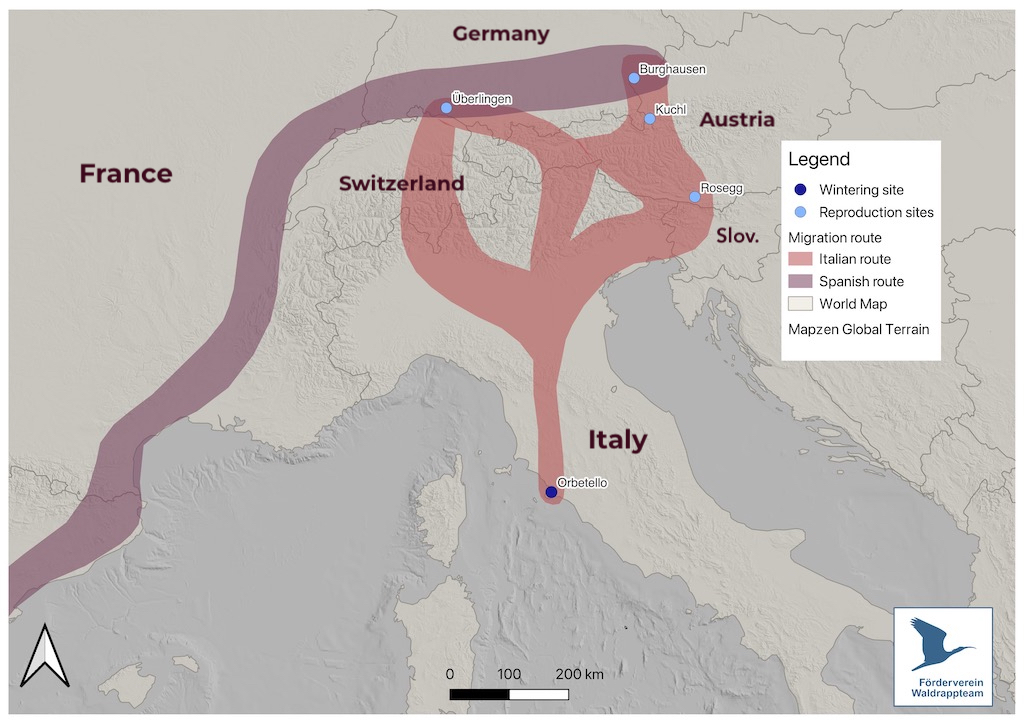

Zoppo was a pioneer. In 2017, he trailed a microlight aircraft from Überlingen in Germany to Tuscany, crossing the Alps. In 2020, he returned alone, becoming the first adult northern bald ibis in over 400 years to do so. His successful return to Lake Constance has transformed the breeding site there into a new European colony.

This year it was the turn of young Zaz to learn the migration route from Zoppo. At just 5 months old, she took flight with him, passing over Switzerland and then braving the updrafts to cross the Alps. The pair successfully made landfall in Italy. Less than an hour later, exhausted and hungry after their arduous journey, they were shot dead while searching for food in a meadow in Dubino, Lombardy.

Zoppo and Zaz were two of only a few hundred northern bald ibises remaining in Europe. The species disappeared from the continent in the 18th century. Since 2004, attempts have been made to reintroduce it. This involves teaching each individual how and where to migrate, by means of manned accompanying flights.

To ensure the long-term viability of the species, experts say that at least 360 individuals are needed. That figure has nearly been reached. Alas, each year more than 100 ibises die (109 in 2024). Many (36 percent) are killed by overt poaching, while others (30 percent) simply “disappear”, likely as a result of unspecified “human actions”.

Another frequent cause of death (34 percent) is electrocution following collisions with uninsulated high-voltage power lines. In 2020 the corpse of young Sonic was recovered underneath one of these unexpected obstacles. Sonic had been the first female northern bald ibis to learn to return alone from Tuscany to Lake Constance, the same route taken by Zoppo.

The details of the deaths are known because of a backpack that the ibis carry on their backs. Inside is a device that reports their GPS coordinates and abnormal movements to a team of experts ready to intervene in case of suspected injury or death.

The northern bald ibis is an endangered species, and an EU-funded conservation project is ongoing to prevent its extinction. LIFE Northern Bald Ibis is the first initiative to attempt to reestablish a migratory species in its historical European range. Such a feat involves reviving a migratory behaviour that has been lost.

Not every migratory bird can be watched over as closely as the northern bald ibises. However, the project does highlight the dangers that many other species also face when crossing the Alps. These include not just unprotected Swiss power lines, but also Italian poachers.

Rampant poaching

After years of carnage, the damage inflicted by power lines seems to be waning. In 2024, the Waldrappteam (“Ibis team”), the Austrian body that manages the ibis project, counted a total of 109 deaths, 22% of which were caused by electrocution near pylons. With a wingspan of up to 135 centimeters, northern bald ibises are among the birds most at risk when high-voltage power lines are spaced too closely. To protect the birds, it is enough to place the wires further apart or to insulate them with plastic sheathing.

Doing so would cost electricity operators around €650 million, an expense they have threatened to add to their customers' bills. Last summer, the Swiss Federal Council (parliament) nonetheless passed a law requiring dangerous power lines to be upgraded by 2040.

There is no sign of such progress in Italy. The two ibis victims of poaching found in Dubino have had no impact whatsoever on Italy’s ongoing debate surrounding Bill 1552, a proposed law to extend the hunting season to include periods that are crucial for migratory species.

Johannes Fritz, research director at Waldrappteam, is worried. “Poaching remains the most serious threat to the northern bald ibis in Italy”, he says. “[It is] an ancient tradition that shows no sign of stopping, even in the case of protected species such as this one, whose killing is punishable by up to six years' imprisonment.” (The penalty features in article 452-B of Italy's penal code.)

In a recent report, “The Killing 3.0”, produced by Birdlife International and Euronatur, Italy ranks first in Europe and the Mediterranean for illegally killed birds, with 5.6 million individuals in the 2022-23 season alone. According to Rosario Fico, head of the centre for veterinary forensic medicine at Rome’s IZSLT animal-health institute, both the report and Waldrappteam's data “unequivocally highlight the systemic weaknesses that characterize the Italian system for combating poaching”.

Fico points to “a serious and ongoing lack of investigation methodology and a failure to understand the social aspect of the phenomenon”. The latter, she believes, is crucial in order to identify both those responsible for poaching and their associates who feel that they have impunity. “It is unlikely that a poacher would act alone”, says Fico. “They would never risk losing their hunting licence.”

The view is shared by Claudio Tomasi, coordinator of the forestry corps of Friuli-Venezia Giulia. In this region, the number of northern bald ibises is growing – as is the number of them killed.

Volunteers race against time

In the summer of 2024, more than fifty birds migrated successfully. Four others were shot, three of them in Udine province and one in Pordenone. Stefano Pesaro, a specialist in wild-animal medicine at the University of Udine, saw the carcasses arrive at the centre for livestock and wildlife management in Pagnacco, which he heads. Pesaro personally performed X-rays and autopsies to provide the Waldrappteam and police with all possible evidence to assist in the investigation.

Pesaro has been collaborating with the Friuli Venezia Giulia region's forestry service and the LIFE project for some time. “I saw my first northern bald ibis 15 years ago. By means of autopsies, we can identify the type and size of the bullets.” He tells us this while tending to an injured young rescue specimen that is hopping around in a large aviary.

A few kilometres from the centre where Pesaro works, Claudio Tomasi, of the forestry corps, agrees that the information gathered in Pagnacco can be vital, especially in cases of poaching. “In many cases of blatantly illegal killings, it is not possible to proceed legally because there is a lack of evidence. A project such as Waldrapp can provide crucial evidence, increasing the likelihood of tracing those responsible.”

This applies not only to the results of autopsies, but also to the coordinates provided by GPS devices and clues collected at the scene of the crime. Gathering the right evidence as quickly as possible is a team challenge in which the role of volunteers is more important than ever. Roberta Peroni, head of anti-poaching in Italy for the ibis project, stresses this point several times as she makes her way through tall grass to reach the site, near Osoppo, where the ibis Brisa was found shot dead.

Brisa’s body was recovered by a local volunteer, whose quick thinking could prove decisive in the investigation to identify the shooter. In Otello's case, rapid rescue efforts had already saved his life twice. When the ibis was very young, a volunteer discovered him with light injuries near Orbetello, in Grosseto province. A few years later he was found by a tourist, motionless and weak, on the seashore near the same area.

Political signals going unreceived

In Italy, efforts are underway to speed things up – both the response to reports of anomalies by the geolocation device, and potential court proceedings.

Meanwhile, in Germany and Austria, research is ongoing into how to improve the performance of the device itself. The goal is to make it more performant for those who consult the data, and at the same time more comfortable and lightweight for the ibises that wear it. Better solar panels promise to make the device more autonomous, and improvements to its GPS component should make it more accurate.

The device weighs 25 grams and is designed to interfere as little as possible with flight, but there is still room for improvement. To identify the most aerodynamic shape, a dedicated wind tunnel was built in Seekirchen am Wallersee, in Austria, thus turning a disused barn into an aeronautical research lab.

The engineer in charge there is Herwig Grogger, an Austrian who has been working with the Waldrapp team for years. He has enlisted his students in this unique conservation project. The two young people currently involved have created a virtual model of the northern bald ibis and a 3D-printed copy to use in the wind tunnel in place of a real specimen. This way they can work on improving the aerodynamics of the “GPS backpacks” without subjecting any real ibises to stress.

With this ongoing research in the barn in Wallersee, Waldrappteam intends to demonstrate that it is possible to make technology an ally of nature. Alone, it will not be enough. In Italy, GPS data has not protected the northern bald ibis from poachers. To save more birds – including the untracked ones – a more traditional human effort is required.

The stakeholders and authorities need to find a way to work together. Veterinarian Rosario Fico believes that “a clear political will to combat poaching would help”. So far, on the Italian side of the Alps, there is little sign of that.

🤝 This article was produced in collaboration with Brigitte Wenger, and supported by Journalismfund Europe

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!