“Sustainability” is the magic word of contemporary marketing. Entering a supermarket, many of us will choose a detergent with a green label, featuring words like “organic”, “eco-friendly” or “recycled”, instead of the generic product, once the green alternative isn’t too expensive.

This is also true in the world of finance, where over the last few years there has been significant interest in Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) investments. According to an analysis by Assogestioni-Censis, almost two thirds of Italian investors are interested in products that take into account environmental and social impact, as well as good governance practices. Asset management companies have been quick to perceive this trend and adapt their products accordingly.

But if the person selling the detergent adds a green label, how do we really know what differentiates it from the generic product? If the parameters of sustainability are lacking in clarity, how can we know the extent to which an investment fund is really green?

ESG products, as IrpiMedia has already highlighted, are often governed by regulations that lack clarity and end up contaminating even the best intentions. In order to better understand the situation, we analysed the main player in the Italian market: Eurizon, the asset management division of the Intesa Sanpaolo group.

Eurizon Capital SGR ranks first in Italy for assets under management, with total assets valued at 394.6 billion euro at the end of 2024. Eurizon also has a significant international presence, with subsidiaries throughout Europe, the United Kingdom, China and Hong Kong.

Intesa Sanpaolo and Eurizon not only excel in terms of volume, but also in terms of non-financial performance, which has endowed them with a reputation for responsibility and attentiveness to ESG concerns. According to the Responsible Investment Brand Index 2025, Eurizon is among the top 10 asset management companies for responsible investment in Southern Europe (out of 29 companies under consideration).

Intesa Sanpaolo has received plenty of recognition for sustainability. For example, in 2025 it was among the 100 most sustainable companies at the global level, according to the Corporate Knights list. It is also the only Italian bank included in the Dow Jones Best-in-Class Indices.

Nevertheless, awards and rankings are not enough to show the extent to which a fund is genuinely sustainable: it is essential to understand how the classification of green funds works at the European level.

According to the European Union’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR), since March 2021 all investment funds fall into one of three categories, based on the degree to which they are attentive to ESG parameters:

- Article 6 funds, which take none of the parameters into account;

- Article 8 funds, or “light green” funds, which promote ESG characteristics in their investments while lacking specific objectives;

- Article 9 funds, or “dark green” funds, have specific objectives for sustainable investment.

SFDR is concerned with transparency rather than labelling, and therefore leaves a lot of room for asset managers to choose their own parameters. While the regulation is relatively strict for dark green funds, the margins are decidedly more flexible for light green funds.

According to Eurizon’s latest sustainability report, the fund’s article 8 and 9 products increased to a total of 350 in 2024, amounting to 156.56 billion euro in assets under management (compared to 306 products the previous year). Of these, 342 are article 8 products, amounting to 153.33 billion euro, while only 8 products were article 9, amounting to 3.22 billion euro. Thus, the asset management company does not have many options for the more discerning investors.

But that is not all. Turning our attention to the article 8 products, which should still integrate ESG criteria, certain critical problems emerge.

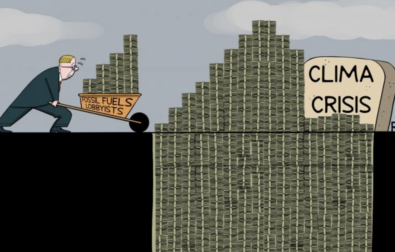

Thanks to a database in the London Stock Exchange Group’s data and analytics suite, we discovered that between the fourth quarter of 2023 and the first quarter of 2025, Eurizon Capital SGR SpA invested 2.49 billion dollars (2.12 billion euro) derived from article 8 funds into fossil fuel companies.

There is admittedly a positive trend that is worth highlighting, namely a clear reduction in such investments during that period. Nevertheless, in the first quarter of 2025 alone, investments passing from light green funds into fossil fuels amounted to 800 million dollars (679.4 million euro).

The majority of these investments flow towards ConocoPhillips (183 million dollars, or 155 million euro), followed by Shell (149 million dollars, or 126.5 million), BP (105 million dollars, or 89 million euro), TotalEnergies (59 million dollars, or 50 million euro), and Exxon (54 million dollars, or 45.9 million euro).

Though they represent only a limited portion of the total assets under management, these figures raise important questions concerning the amount of elbow room that asset managers have when it comes to sustainability.

In the sustainability policies of all the light green funds analysed, it is specified that the maximum quota that a fund can invest in businesses active in the fossil fuel sector is zero percent.

Some of the funds analysed manage to satisfy these guidelines while still investing in fossil fuels, by having exposure of between 0.36 and 0.57 percent (calculated by comparing the total invested in fossil fuel companies and the total assets managed for each fund). For other funds, this exposure is low, but over the threshold, between 2.69 and 2.81 percent.

Furthermore, two of the companies in which Eurizon has invested, ConocoPhillips and Shell, are also actively involved in oil sands extraction projects in Alberta, Canada. Oil sands (or tar sands) are deposits of bitumen that allow oil to be extracted after several stages of processing. They have been called “the world's dirtiest fuel” because of their environmental impact.

Eurizon claims to exclude investments in issuers involved in oil and gas extraction activities that rely on tar sands, if they derive at least 10 percent of their turnover from those activities. The ConocoPhillips and Shell documents that we consulted do not specify what percentage of turnover derives from such activities.

Only the products that are claimed to be in line with the Paris-Aligned Benchmark (PAB) – a financial index that serves as a reference to trace the alignment of a business with the climate objectives established by the Paris Agreement – must explicitly exclude businesses linked to fossil fuels (such as coal and lignite, petroleum fuels or gas) or those with a high environmental impact.

According to the new European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) guidelines, the same exclusions apply to products that use terms such as “ESG” and “sustainability” in their name. Of the Italian Eurizon funds analysed that continue to invest in fossil fuels, eight contain terms such as “ESG”, “Net Zero”, “Social” and “Sustainable”, indicating environmental and social sustainability (also included in the ESMA guidelines).

“There are cases”, experts have noted, “where instead of divesting from oil and gas they prefer to maintain the investment in order to pursue a dialogue with the companies and be able to influence their strategies in the long term, with a view to ecological transition.”

Despite these critical issues, Eurizon claims to be focused on a long term strategy aimed at climate neutrality. Indeed, Eurizon is a member of the Net Zero Asset Managers Initiative, an international coalition of asset management companies that are committed to reaching net zero emissions by 2050, and orient their investments in this direction.

The signatories commit to collaborating with their clients to gradually decarbonise all assets under management, setting interim targets that are to be updated every five years. In theory, the proportion of assets under management that meet the criteria of climate neutrality should increase over time until it reaches 100 percent. Since January 2025, the initiative has been under review to ensure that it remains “fit for purpose in the new global context” – a reference to recent developments in the United States and the departure of major players such as JP Morgan from the initiative.

For this reason, monitoring implementation and reporting by signatories has been suspended, and the declaration of commitment and list of signatories have been removed from the website. In its presentation of its own approach to responsible investment, Eurizon claims it has defined four objectives to achieve climate neutrality.

The first of these concerns the identification of the so-called “portfolio in scope”, or the portion of assets that will be managed according to the objective of achieving zero emissions by 2050. This portfolio, as defined in 2021, represented only 15 percent of total assets under management, amounting to around 67.5 billion euro.

In other words, only a minimal proportion of assets are meaningfully tied to the 2050 climate neutrality objectives. For the remaining 85 percent of assets, Eurizon contents itself with a generic commitment “to achieving this for 100% of its activities over time”.

Efforts have certainly been made to clarify what is really meant by “sustainable”. One of the pillars of the relevant European regulation is the Taxonomy, introduced in 2020 with the objective of defining in an unequivocal and standardised manner which economic activities can be considered sustainable.

In its Sustainability Policy Summary document, Eurizon cites the Taxonomy as part of the regulatory framework on which it bases its own environmental policies. However, all the Eurizon funds analysed report zero alignment with the Taxonomy.

The documentation explains that this does not exclude the possibility of future investments in ecologically sustainable activities, though it does not provide any mandatory minimum threshold.

So what went wrong? In this case, the problem is shared by most of the European asset management sector, which often prefers to declare zero alignment in order to avoid errors or sanctions due to interpretive margins in the regulation.

According to Roberto Grossi, deputy director of Etica SGR, after an initial burst of energy, the European Commission appears to have lost its momentum. The two key regulations (the Taxonomy and the SFDR) are not well coordinated with each other and are already under review. Given the regulatory uncertainty, the financial operators are being urged to “be cautious in a context that could change rapidly”, as the Forum for Sustainable Finance has declared.

Further complicating the situation, the recently approved Omnibus package allows for a reduction in reporting requirements for small and medium-sized businesses. This, Grossi observes, creates a structural contradiction: “asset managers are rightly asked to make commitments if they want investments to be green, but the same level of transparency is not expected of businesses. If the businesses are not required to share their figures, how can I verify the sustainability of an investment?”

This inconsistency is compounded by further difficulties: the data on sustainability is often fragmentary or difficult to collect, even for the companies themselves. This is partly due to globalised supply chains, which are subject to widely varying regulations.

Since the European regulations do not allow for estimates or approximations, many asset management companies prefer to declare zero alignment in order to avoid exposing themselves to the risk of greenwashing accusations.

Intesa Sanpaolo did not respond to our request for comment.

👉 Original article on IrpiMedia

This article is published in collaboration with IrpiMedia; it is part of Voxeurop's investigation into green finance and was produced with the support of the European Media Information Fund (EMIF). The sole responsibility for any content supported by the European Media and Information Fund lies with the author(s) and it may not necessarily reflect the positions of the EMIF and the Fund Partners, the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation and the European University Institute.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!