Situated in the inner courtyard of a Hausmannian building in Paris is Espace Libertés/Reforum Space. Here you can find a segment of the Russian-speaking diaspora – mostly Russians, but also Belarussians, Kazakhs and Ukrainians – who oppose the war in Ukraine and were forced to leave Russia: political opponents, journalists, artists, LGBT+ people, deserters.

The list is neither exhaustive nor complete, nor even perhaps relevant, because nowadays it takes very, very little for an act to be considered subversive. “You can be sentenced to several years in prison for simply calling the war a war, and not a special operation,” says Olga Kokorina, director of the centre, “or for clicking ‘like’ or posting a comment on YouTube”, or for “donating ten dollars to the Ukrainian army”. Indeed, Russian civil society as such is at risk, simply for existing.

Olga, along with others, founded the Russie-Libertés association in 2012: in the beginning its aim was to “be the spokesperson of the resistance and opposition in exile, and represent Russian civil society” in order to raise awareness in French and European society about the violation of human rights in Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

The turning point was the full-scale invasion of Ukraine: “we realised that we could no longer just inform people. We needed to be in a position to welcome political immigration”.

In France, thanks to the already well-developed savoir faire of Russie Libertés and a number of other entities such as the Agency of Artists in Exile, obtaining a residence permit is relatively easier than in other European countries, at a time when it is generally a complex and difficult process.

Espace Libertés is a good example of how an association can manage a significant part of welcoming an immigrant community in a given country. A resident who needs a well-equipped coworking space to continue working on a project involving democracy in Russia or opposition to the war is provided with their own space, and several volunteers can provide help. To date, more than 400 people have been accommodated.

There are language courses, legal support for navigating the French system, psychological support and an audiovisual recording studio. Maya, in charge of technical support, shows me around on a February afternoon. As she sits at the recording desk and shows me the equipment, Maya explains the different types of content that are produced: artistic projects in both audio and video (many directors who have been welcomed to the space), but also journalistic content for media organisations such as Doxa or Verstka. There is also content produced by former soldiers of the Russian army explaining how to (attempt to) defect and flee Russia.

The story of Russie-Libertés is also the story of how the Russian political panorama has changed. “In 2012 political immigration was still a marginal occurrence. It was mostly Chechens and Ingush people, for example. This was when Ramzan Kadyrov took power in Grozny. Then we saw the situation change when the Foreign Agent law was introduced. Around the same time we began to see human rights defenders, journalists, activists…”.

The year 2022 was another turning point. While the increasingly authoritarian transformation of Putin’s regime was hardly subtle, “the beginning of the full-scale war was a point of no return. Russia has become not just an authoritarian country, but a fascist country, a dictatorship. The repression has become extremely violent”.

Depending on the definition of political prisoner, conservative estimates suggest that there are anywhere between 772 (according to the NGO Memorial) and 1300 (OVD-Info) such prisoners.

The situation in Russia is one of generalised terror, explains Matvey (the name has been changed): “it wasn’t me yesterday, it wasn’t me last year, it could be me any day”. Matvey is a 26 years old LGBT+ activist who arrived in France about five months ago. In Russia, a law against “LGBTQ+ propaganda” was passed in 2013, and then reinforced in 2022, leading to the prohibition of texts, films and artworks that were deemed propaganda.

In 2023, gender transition was banned by law, and the Russian Supreme Court judged the so-called “international LGBT+ movement” responsible for “extremism”, leading to the closure of the last remaining associations. Gay bars were shut down, and people were prosecuted (even for posting ads on dating sites).

To put into perspective how profound this shift has been, Russia’s Eurovision entry in 2003 was t.A.T.u., a group who played very openly with queer coding ( though one of the singers, Yulia Volkova, later made homophobic statements).

On the issue of gender transition the backtracking is even more incredible. As Matvey explains, Russia used to have one of the most advanced laws in the world: adopted in 1997, it allowed people to transition after a few months of medical examinations, by simple administrative decision. Today, the people who have benefited from this law since 1997 can no longer adopt or have a child under their guardianship, and marriages that were registered during that period are now annulled. Cases of people being forced into “conversion therapy” are constantly increasing.

The “regime of terror” and its propaganda are increasingly invasive, Matvey tells me, and it begins “in nursery schools”. The war is destroying the country, he says, and, “although it is not even close to what the Ukrainians are facing, I think that for the next 20 years Russia will be an extremely sad, poor and destroyed place, all because of one man’s crazy ideas”. Beneath the far-reaching political questions are individual stories of pain and separation: “my mother, for example, is broadly pro-state, because she gets all her information from official channels, whereas my aunt is deeply anti-war”.

In the same social circle the positions can be – and are – very diverse. “My mother wasn’t particularly happy with my departure, while my aunt said ‘go, escape and don’t come back’. Cheers to my aunt!”

The refrain of “Russia supports Putin” is overpowering in public discourse and the media. It is impossible to obtain official data on Russians who have left the country, but the number is thought to be in the hundreds of thousands.

Above all, besides the limited data from independent sociological research, it is difficult to tell what Russians are really experiencing and how they live, bombarded as they are by propaganda, under a regime that has lasted for over 20 years. “People are afraid, and those who remain develop different forms of resistance,” Kokorina tells me. “For example, I know of a lady in her 80s who, as soon as there is a demonstration, takes her shopping cart and marches alongside the protestors. And if the police arrive, she says she was only there because she was going shopping”.

There are many who cannot or do not want to participate, for infinite and practical reasons.

“You try to get around censorship. For example, the environment, which is a battle that is still not considered terrorist, brings together LGBT+ people and feminists. But they have to be careful about what they say,” says Kokorina. She adds that there are many clandestine initiatives, including one group that deals with emergency evacuations of people in danger all over Russia, and connects over 8,000 people on protected communication networks that are activated when needed. “But Russians are resisting. We no longer call them activists, but resisters. Whether they are the majority or the minority I cannot tell you, but in any case Russian civil society still exists”.

Espace Libertés has been open since February 2024, and its existence is already at risk; not because of the dictatorial regime in power in Moscow but, like so many entities of this kind, because of the US administration’s cuts to USAID (United States Agency for International Development).

The space receives funding from the Free Russia foundation, an American think tank (considered “terrorist” in Russia) that brings together some of the best known names in the Kremlin opposition, including Vladimir Milov and Vladimir Kara-Murza. The Free Russia Foundation used to have many local branches across central and eastern Europe, including in cities such as Tallinn, Berlin, Warsaw, Kyiv, Tbilisi and Vilnius. Today, only three remain.

‘The rise of the right-wing parties with ties to Putin create massive concerns. Say the right-wing become part of a ruling coalition: who can guarantee there won’t be a deal between them and Putin involving kicking out or arresting the most active opponents of Putin’s regime abroad?’

Yulia Abdullaeva, coordinator of the Reforum Space in Berlin, which gathers around 900 people every month, explains that the situation for Russian refugees in Europe is complicated, and varies from country to country. “France, Germany and Poland offer some support, including social programmes, but bureaucratic obstacles are often insurmountable. In the Baltic countries, which have experienced a large influx of Russian emigrants, the situation is unstable and the paths to long-term residence or citizenship are virtually closed. In countries like Spain or Portugal, visa procedures may be more simple, but social integration is more difficult and the Russian-speaking communities are smaller”.

From Paris to Berlin, from Vienna to Monaco

A Russian activist in Austria who wishes to remain anonymous recounts the difficulties of migration: “It’s hard to move to Austria: finding a job without a network is damn hard, scholarships to study at the university are thin, and it certainly does not help that financial institutions deny service based on an incorrect reading of the sanctions [...]. Getting involved in activism at the same time is not sustainable in the long term, and our community has lost some of its most active members for exactly this reason”.

Moreover, the political environment on the continent hardly helps: “The rise of the right-wing parties with ties to Putin create massive concerns. Say the right-wing become part of a ruling coalition: who can guarantee there won’t be a deal between them and Putin involving kicking out or arresting the most active opponents of Putin’s regime abroad?”

“We are talking about a person, who launched the largest war in Europe since the end of WWII as a leader of a country with the largest nuclear arsenal in the world. If there is a definition of a threat, then it should be that.” The activist adds that “it is important to remember that Putin is a product of an unchecked power, political and economic inequality, and an atomised society. And these things are not unique to Russia.

These are global trends – and developed nations, including Austria, are part of it. As the ascent of populists around the world shows us – Trump being the prime example – we are on a slippery slope and we need to start taking our future in our own hands by building politically active communities that protect the people and the common good, not the private interests of a few selected people in the higher ranks.”

For others, social and professional integration is more simple. “I left Russia in 2019. I now live abroad and continue my activism from exile”, says Dmitry Kovalev, who lives in Munich. “I’m a software developer, which made the process of resettling significantly easier than it is for many others”. Dmitrij has continued to work for “The Left For Peace and a World Without Annexation” (“Левые за мир без аннексий”), a group that is opposed “to all the annexations of Ukrainian territory since 2014” and demands “unconditional support for the Ukrainian people”.

As Dmitry explains: “This includes military, humanitarian, and financial aid from Western countries—without hesitation or compromise. The term ‘opposition’ in Russia today is broad and fragmented. It includes pro-war nationalists, centrist liberals, liberal defeatists, and a wide spectrum of leftist groups with differing positions on Ukraine”.

Nevertheless, “only the left offers a truly anti-war position rooted in systemic analysis and international solidarity. What defines the left opposition is our defeatist stance—we believe that Russian imperialism must be defeated, and we use Marxist and leftist theory to support and explain this necessity”.

At the same time, he concludes, “being on the left means understanding that the EU and USA are also imperialist actors with their own interests. Unlike liberals who tend to idealise the West, we critique Western policies—such as exploitative rare mineral deals or the insufficient and inconsistent military aid to Ukraine.”

Mariia Menshikova left Russia in 2020, not due to the political situation, “but only because I wanted to do my research.” She left for Germany to begin her doctorate, thanks to a grant. “I was lucky. It was very easy to settle because it was all planned. I was also planning to return to Russia after I finished my thesis. But now it’s impossible because I am wanted by the authorities in Russia”.

Menshikova, who edited the independent online youth magazine Doxa (now labelled “undesirable” by Moscow), was sentenced on 30 September 2024 to seven years’ imprisonment for “justifying terrorism” in two posts published on the Russian social media site VKontakte in 2022.

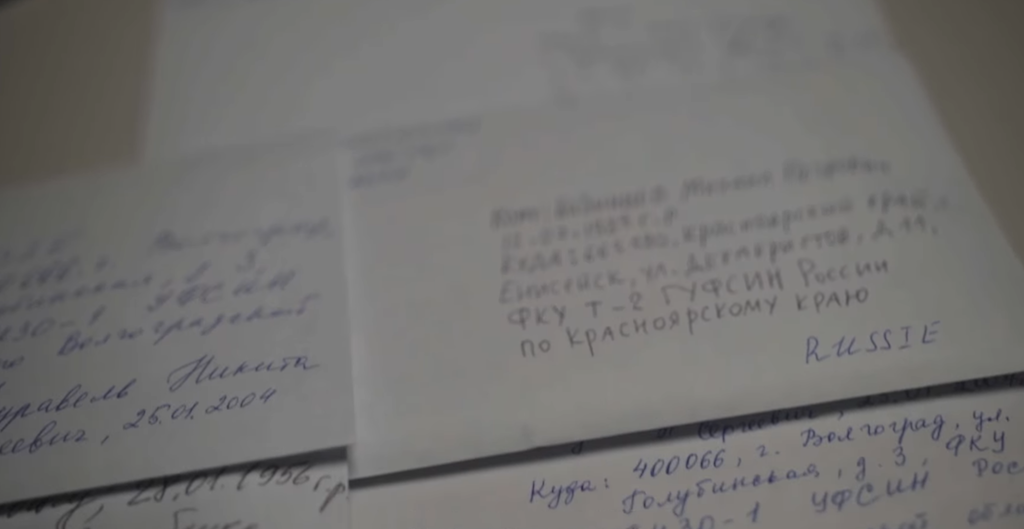

In Russia there is no real opposition, she explains, “because the parliamentary opposition is an integral part of the regime. There are people who protest and organisations that are against the regime. For example, various militants, including anarchists, who commit acts of sabotage against railways [which transport military convoys], or who organise initiatives to support political prisoners, writing to them, collecting funds for legal aid, and so on”.

That said, Menshikova concludes, “my personal hope is connected to the question of unions, because real independent unions continue to exist in Russia, though they currently have no space to act. But they are important as institutions that have organizing skills that we will need with the beginning of the great social transformation that I hope is going to happen in Russia”.

🤝 This article was written as part of the PULSE project. Angelina Davydova from n-ost, Kim Son Hoang from Der Standard and Gian-Paolo Accardo from Voxeurop contributed.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!