Sara* is 43 years old and works as a freelancer in Italy. Like many of her colleagues, she regularly participates in European funding opportunities for journalism, such as JournalismFund Europe or Investigative Journalism for EU. Sitting at a table in a park in northern Paris, Sara tells me about a highly instructive episode: while preparing the budget for an investigation with a colleague from another European country, the latter suggested that she had forgotten a zero.

For her colleague, the expected pay for a report in a French media outlet was 500 euro, and for Sara, 50 euro. “Mine is not an isolated case,” she tells me. From reportage to in-depth articles, Sara is paid “a minimum of 50 and a maximum of 120 euro per article. A 50 euro article can include travel, several interviews and photos. You practically work for free”.

Sara, again like many of her colleagues, finds herself relying heavily on journalism grants. In addition to the economic issue – which is central – this also raises another question: the quality, relevance and form of the information produced. “This mechanism very much limits the topics chosen. If you want to conduct an investigation on an Italian subject, you have to make it cross-border to qualify for these grants”. What does this mean? It means that you have to make it part of a broader European theme. This may enlarge the perspective of the articles, but it can also dilute the impact when compared to a story focused on one country. “Quality and purpose have to take a backseat when you’re chasing grants,” she explains.

Sara is paid ‘a minimum of €50 and a maximum of €120 per article. A €50 article can include travel, several interviews and photos. You practically work for free’

For freelancers in Italy, getting properly paid for investigative work – leaving aside all the legal risks – is virtually impossible. Journalists in Italy, Sara tells me, “are very concerned. The real problem is that in order to be able to sell an article you often have to neglect important topics and uncomfortable investigations because Italian newspapers don’t want them or are afraid of them, and you have to make pitches sexy for the daily news cycle... It’s this, above all, that impacts so much of our lives as freelancers as well as the Italian media landscape”. Sometimes, Sara adds, “you get the impression that your work is a mission”.

According to Eurostat data, in 2023, 868,700 people were employed in Europe as authors, journalists and linguists (all are included in the same statistical category): Germany leads with 237,600 people, followed by France with 92,800, then Spain (74,200), Italy (72,300) and Poland (69,600).

Italy, France and Spain provide an interesting starting point for a comparative reflection on the issues. They are also three countries for which the journalists involved in the Pulse project were able to collect testimonies and data.

In France, according to data from the Commission de la Carte d’Identité des Journalistes Professionnels (CCIJP, which issues press credentials each year), there were 34,444 professional journalists in 2023. The number corresponds to the number of press credentials issued and/or renewed.

In Italy, according to National Order of Journalists data, as of January 2024 there were 94,086 journalists registered with the organisation (of whom 26,086 are so-called “professionals”, i.e. those who exercise their profession continuously, and 68,000 are “publicists”, i.e. those who exercise their profession non-continuously).

In Spain, on the other hand, there is no such official list. According to Eurostat data (which includes other professions), the sector employed 74,200 people in 2023, in a country with about 49 million inhabitants.

France has about 68 million inhabitants, Italy about 58 million. Italy has three times more journalists than France.

“Let’s be clear: there are just under 100,000 members of the Order of Journalists, but there aren’t 100,000 jobs for journalists in Italy,” says Alessandra Costante of the National Federation of the Italian Press (FNSI, the country’s largest journalist union, with 16,000 members in 2023). “Given supply and demand,” Costante continues, “this dynamic is impoverishing the sector”.

In Italy, €50 for an article

“Not only is journalism in Italy getting poorer and older, it is also more precarious. Precarity is the biggest muzzle on the freedom and independence of the media and on Article 21 of the Constitution,” says Alessandra Costante.

Journalism in Italy is suffering. It is suffering from stress, it is suffering from precarity, and – as a consequence – it is suffering from a lack of quality. The most comprehensive survey to date on the subject, with 558 participants, was published in IRPIMedia in 2023 by Alice Facchini. “The factors that are identified as having the greatest impact on psychological well-being are first and foremost instability and precarity, followed by inadequate pay, always being connected and on call, and a frenetic pace,” Facchini says.

So who are these people? “46% are between 18 and 35 years old, 31% are in the 35-45 age bracket, 14% are in the 45-55 bracket, 6% are in the 55-65 bracket, and only 2% are over 65”. More than half of the respondents (65%) describe themselves as “freelancers”. The IRPIMedia survey highlights an issue that may seem trivial: “Inadequate pay is considered to have the biggest impact on the psychological well-being of this category of worker”.

In Italy, “six out of ten journalists earn less than €35,000 a year” writes La Via Libera (INGP data, Report on employment dynamics in the journalism sector) and “almost half of freelance journalists – who are often precarious collaborators or on VAT numbers – earn less than €5,000 a year, and 80% earn no more than €20,000”.

Alessandra Costante explains that “the Order used to have a fee schedule that indicated the minimum salaries for those working in the profession on a self-employed basis. In 2007, the Competition and Market Authority requested its removal. With the renewal of the national collective labour agreement signed by FNSI and FIEG (Italian Federation of Newspaper Publishers) in 2014, a specific agreement on self-employment was introduced that sets some minimum guarantees, both in economic terms and in terms of protections and rights, for freelance journalists with coordinated and continuous collaboration contracts”.

In fact, the pay rates in Italy are those decided by each media outlet.

Lo spioncino del Freelance (”The Freelance Peephole”) is a website modelled on the French Paye ta Pige, a project designed to bring transparency to the press. Lo spioncino del Freelance actively monitors how much freelance journalists are actually paid in Italy. Francesco Guidotti, one of the founders, says that “it is a little complicated to establish an average that effectively represents the whole sector based on our data. We include heterogeneous and sometimes very different forms of collaboration. One sum that is often reported is €50 gross, which is paid for in-depth articles that can take several hours to produce. There are also short news items paid between two and ten euro gross. Payments as high as €200 or €600 gross are very rare, but are often received for reports or longform articles for which journalists have to travel, study and work for several days”.

The aim of Lo Spiocino del Freelance, Guidotti explains, is limited to “making pay transparent”.

“We think that it should be the trade unions that intervene,” says Guidotti, “and to some extent they are doing so, though surely a movement from below to demand better pay would help. We would like to try to organise something in this direction, but it requires time and energy, a rare commodity for freelancers. In the meantime, we think it is also up to the individual freelancer to negotiate, to say no to humiliating rates, etc., and we hope that making remuneration transparent can raise more awareness. Then they may still say that young people simply don’t want to work, but at least they will realise that there’s a genuine problem”.

‘I haven’t found a Spanish media outlet that pays more than €100 per piece of reportage’

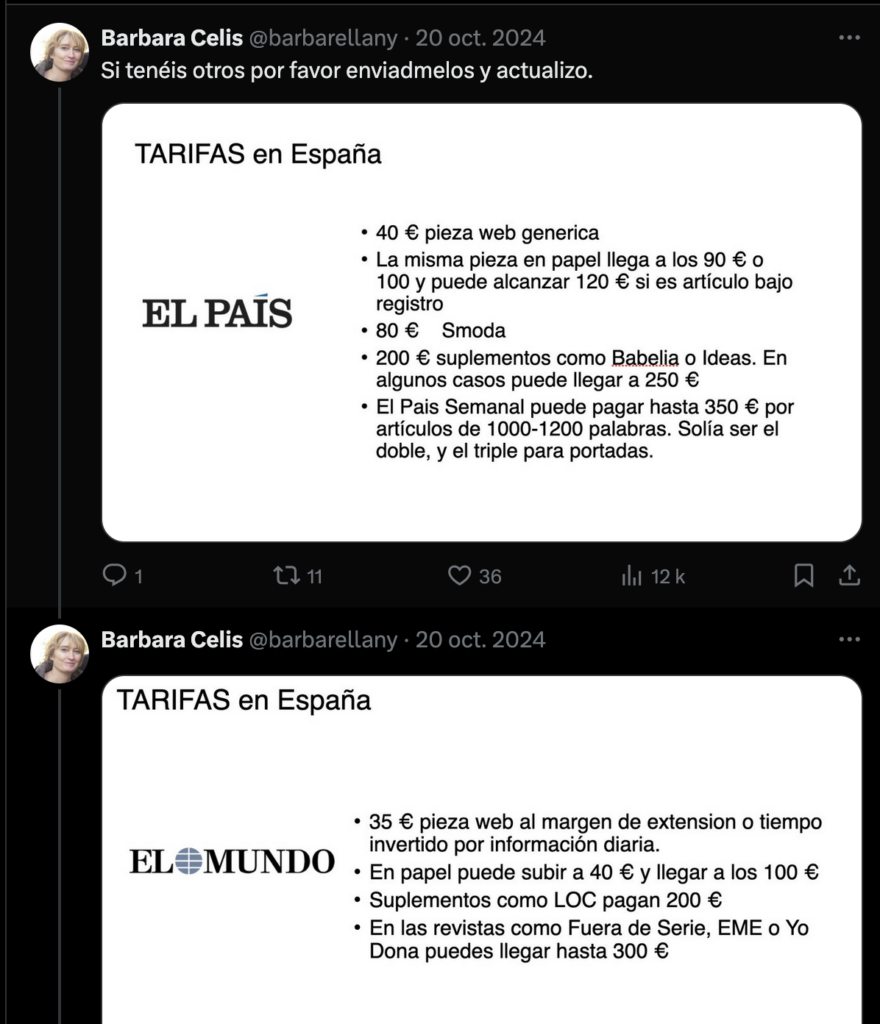

In Spain, the situation seems no better than in Italy, and the rates for freelancers appear to be similar. Some national newspapers pay between €35 and €40 per article, as this discussion on X indicates.

Esperanza* is 36 and has been working as a journalist for 11 years. “I haven’t found a Spanish media outlet that pays more than €100 per piece of reportage” she says, “no matter how much time you spend on it. Most pay between €50 and €70. For example, in 2016 I followed the refugee route in the Balkans, and a big media outlet paid me €70 for the report”.

In the past, says Esperanza, “I worked for seven years at Cadena SER. During my last two years there, I asked my superiors to move me to a different section because of my boss’s misbehaviour (shouting, inappropriate comments, ridicule). All this occurred in an environment where I was earning only €600 a month as a false autónomo. It was considered normal there to spend 10 years or more as a ‘false freelancer’, waiting for a regular contract. Since I could neither get a transfer within the company nor find the time to look for work elsewhere, I ended up leaving without any prospects”.

According to figures from the Spanish Labour Statistics Office, the average salary of a journalist in Spain is €22,000 per year. An additional problem is that many journalists fall into the category of “false autónomo”, i.e. freelancers with VAT numbers who are used to fill positions that would otherwise be permanent. This allows many newspapers to hire without hiring. According to the Public Employment Service (SEPE), between September 2022 and 2023, there was a 6 to 14% increase in false freelancers compared to 2022.

In Cuardernos de Periodistas, a specialised newspaper, Cristina Puerta wrote in 2022 that in Spain there are more than 73,500 people registered as freelancers. Puerta cites a Madrid Press Association (APM) report, according to which 69% of self-employed journalists adopt this status out of necessity, not choice. “In Spain,” Puerta writes, “protection of their rights and working conditions, or access to social benefits within a legal framework, are practically non-existent and far behind the regulatory measures of other European countries such as France”.

‘It was considered normal there to spend 10 years or more as a “false freelancer”, waiting for a regular contract’

According to Ana Martínez of the Comisiones Obreras (CCOO) trade union, “job insecurity is the major characteristic of media workers in Spain. Since the economic crisis of 2008, journalists, camera operators, photographers and technical staff working for news services have lost between 25% and 30% of their purchasing power: salaries have not increased at the same rate as inflation”.

A 2016 research study, La precariedad en el periodismo: una historia de largo recorrido, reports that “the precarity of the profession, which has given rise to the term precariodismo (a neologism combining precariedad, precarity, and periodismo, journalism), has led to growing academic interest in the working conditions of journalists”.

France, a case apart?

In France, the Observatoire des métiers de la presse, which analyses developments in the profession, publishes a report on the income of journalists based on data from the CCIJP, the body that issues press credentials. The data only includes card holders. In 2023, 69.8% of journalists in France worked on a permanent contract with a gross median salary of €3,650, 23% worked as freelancers (pigistes) earning 1€,951 gross, and 2.2% worked on a fixed-term contract for €2,958 gross.

Remuneration for French freelancers is regulated at €60 per page (i.e. 1,500 characters). Each media outlet then applies its own rates independently.

Pauline, from the association Profession : Pigiste explains that in France, “rates vary widely. There are minimums, but they are not always respected. Sometimes articles are paid by the piece, but if they are paid per page, they end up being paid €20 or €25 per page. On the Paye Ta Pige website I saw a rate of 18 euro per file, paid as an invoice and not as a salary, as required by French law (which means that not only is the rate very low, but the journalist does not even contribute to health care, unemployment, pension, etc.). As for the maximum range, to my knowledge it is around €150 gross per file. Perhaps others offer even higher rates. But this maximum band is rarely applied. In general, though cases of extremely low pay certainly exist, they are rare”.

The pige system is unique to freelance journalists in France. In fact, it is a “mini salary”, the status is that of an employee, because the client also pays social contributions. It is defined by the 1974 Cressard law.

A European situation?

Jana Rick is a PhD student and research associate at the Department of Media and Communication at the Ludwig Maximilian University in Munich. Her research project Prekarisierung im Journalismus (”Precarisation in Journalism”), conducted between 2019 to 2024, was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and involved one thousand journalists in Germany.

According to the study, 43% of journalists perceive their working situation as precarious, three out of five report that their working conditions have worsened since the coronavirus pandemic, and more than half (58%), think that precarious conditions threaten the quality of journalism. Nevertheless, more than two thirds (69%) of the respondents are generally satisfied with their profession. The German journalists’ union Deutsche Journalistinnen– und Journalisten–Union (dju) reports that about two thirds of its members identify themselves as freelance journalists.

“Some of those journalists admit precarity influences their work,“ Jana Rick explains. “Existential threats may have negative consequences on creativity, lack of time leads to less intensive research. Precarious working conditions may also have a negative impact on the topics journalists choose as they prefer less time consuming topics.”.

The World Association of News Publishers (WAN-IFRA, an organisation with a presence in about 100 countries and more than 18,000 press organisations) published a survey in April 2025 which reports that 60% of the journalists interviewed have experienced burn-out, while 62% are forced to supplement their income with other types of work to make ends meet. The survey is based on about 400 interviews across 33 EU countries, in 13 languages, conducted by Taktak Media/DisplayEurope.

“If the news industry continues its transition to a freelance-dominated model, we will need to invest much more in protecting these workers,” comments Jeff Israely, director of Taktak. “The rise of freelance journalism in Europe is a structural shift in the media industry, as shrinking newsroom budgets have forced outlets to rely more on independent journalists”.

* names were changed at the people's request

🤝 This article was produced as part of the PULSE project, a European initiative to support cross-border journalistic collaborations. The data is not always consistent or comparable, given the different contexts of the media organisations that agreed to participate, as well as the different national contexts. This work should therefore be understood as an overview of a general malaise within the profession in Europe, especially among freelance journalists, and opens up the question of a common regulation for the various employment statuses within the profession.

🙏 For their work, patience and contributions to this article, I would like to thank Lola García-Ajofrín, Ana Somavilla (El Confidencial, Spain), Harald Fidler (Der Standard, Austria), Dina Daskalopoulou (Efysn, Greece), Krassen Nikolov (Mediapool, Bulgaria) and Petra Dvořáková (Deník Referendum, Czech Republic).

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!