Sixteen-year-old Somali girl Maryam's dream is to become a doctor. She arrived in London in 2021 with her mother and siblings, to join her father. She did not speak English. Maryam attends secondary school and will be taking the exams for the GCSE (General Certificate of Secondary Education) this year. She is anxious: she knows that with her level of English it will not be easy to get a good grade. Standing between her and her dream is the reality of an education system that continues to make things hard for non-natives.

Among immigrant minors, teenagers are the ones who have the hardest time integrating at school. They are the "late arrivals": girls and boys who are facing the trauma of migration at a delicate age. They are asked to acquire almost impossible skills within a short period of time. The problem is common to several European countries and affects thousands of adolescents every year: those who arrive with their families; unaccompanied minors; economic migrants; asylum seekers and refugees.

We cross-referenced the experiences of Italy and the United Kingdom. The two countries have similar stories to tell, despite their different educational systems.

Teacher role and exam challenge in London

It is not easy to count migrant students. In the UK, they fall into the category of "EAL students" (English as an Additional Language, i.e. pupils whose native language is not English). In England there are over 1.6 million EALs, which is 19.5 percent of all pupils (Gov.uk data 2021). In Italy, on the other hand, citizenship is taken into account. According to the latest survey, there are 865,388 non-Italian pupils, representing 10.3 percent of the total (Ministry of Education data, Miur 2020-21). However, these numbers also take into account children born in the country (in Italy, this is more than half of them) or who arrived as infants.

In Europe every child has the right to an education. All EU member states, plus the UK, have ratified and incorporated the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child into national legislation. In both Italy and the UK this applies to irregular minors, if they are of compulsory school age. But, right from the start, the path they face is arduous.

Maryam enrolled in school ten months after arrival and her case is no exception. A migrant family does not speak the language, and so cannot easily get informed or negociate the bureaucracy. In London as in Rome, many schools have no free places, with children staying at home for months. In London, secondary schools are reluctant to take 15- and 16-year-old EAL students (year 10 and 11 classes) because of the high risk they will fail the GCSE exam.

Such failures affect the grading by Ofsted (Office for Standards in Education), the body responsible for assessing the quality of education. The result is that the school's reputation deteriorates.

City Heights E-ACT Academy, where Maryam studies, is located in the multiethnic suburb of Tulse Hill in south London. The area is characterised by poverty and social deprivation, and the school is known as an inclusive one. Headmaster Errol Comrie shows us the pile of applications on his desk. They arrive every week, and 50 new pupils have enrolled in the last six months. Out of 600 students aged 12 to 16, fully 263 are EAL. There are Latin Americans, Portuguese, Somalis, Angolans and Afghans.

Andreia Galrinho, in charge of admissions and initial assessment, works with a passion, even out of hours. "For pupils like Maryam the main aim is to learn the language," she says. "Otherwise, in a science or literature class they will be unable to participate or learn."

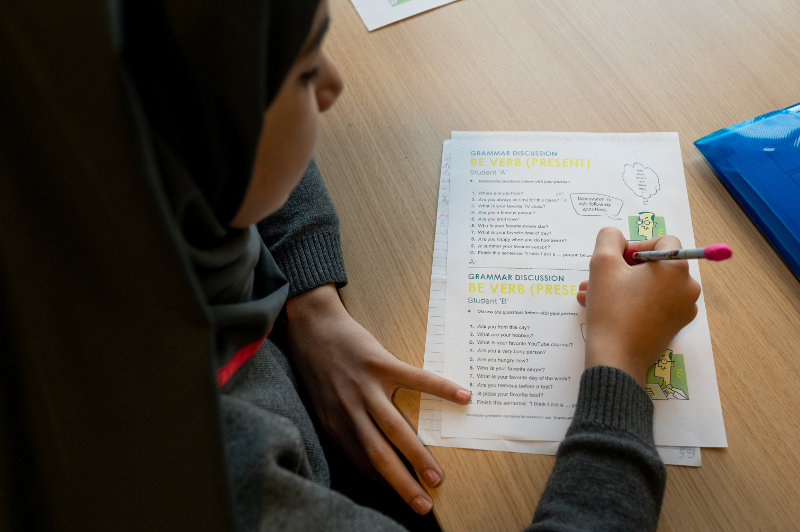

Maryam attends a separate class for EAL students every day. The teachers do their best, and sometimes there are personalised study plans, but the workload is heavy enormous. The children are of different ages, with different school experiences and backgrounds. Some are illiterate while others are already highly educated.

Like many others, Maryam entered school at the toughest time: the run-up to the GCSE exams. Her curriculum is reduced to three subjects (English, maths and PE), but this is still challenging for a newcomer. The grades she gets will affect her future plans, as many universities demand minimum grades at GCSE. In the English school system, you cannot repeat the year: if you fail, you continue your studies anyway. If you want to pursue a particular career, you will have to repeat the exams in order to get the required grade.

But it is a difficult path. Many pupils become discouraged and take the vocational education route. "It is a selective system, full of barriers, where initial inequalities are reinforced instead of being reduced by education," says Federico Farini, a professor of sociology at the University of Northampton.

In Rome, a welcome with difficulties

Like City Heights, the Istituto Comprensivo Simonetta Salacone in Rome, in the crowded and multicultural neighbourhood of Tor Pignattara, is an inclusive school. It includes the Carlo Pisacane primary and the Rosa Parks secondary. 92 out of 225 students (41 percent) have foreign citizenship, with 18 nationalities represented. Many are second-generation, but arrivals are ongoing, from Bangladesh, Pakistan, Peru and Afghanistan. "In the classroom we have a whole world, with different religions, cultures, histories and experiences. Sometimes it goes smoothly, sometimes it is very tough," says headteacher Rosanna Labalestra. The classrooms we see are decorated with murals and posters. "There is not a month in which a family does not knock on the door. This is our priority: we welcome those who come from another part of the world and urgently need to go to school."

Halida and Jamal, 14-year-old twins from Guinea who recently arrived, are learning Italian. They have been attending school for five months and in June they will have an exam which concludes the first cycle of Italian secondary school. They have a personalised study plan and attend Italian language lessons for two hours a week. Unusually, the school is open in the afternoons, and offers help with homework, as well as sports and other activities. But, the teachers ask themselves, how will they cope with a more complex programme next year?

As soon as they arrive, the siblings are faced with an important issue, the question of upper secondary school. Their exam grade will not be decisive, but those who know little Italian are unlikely to go on to “liceo”, the high school. Teachers often recommend technical or vocational schools instead, because they are considered easier. Halida and Jamal arrived at a critical age. Those who arrive as children have more time to learn and adapt.

For boys and girls who have reached the age of 16 (when compulsory schooling ends), there is the option of attending a CPIA (Centro per l'Istruzione degli Adulti), a public afternoon school that receives mainly foreigners (including many unaccompanied minors). Here they can "catch up" with the relevant exams. But to enrol between the ages of 14 and 16 is always difficult. Second grade secondary schools generally have less support for newcomers and tend to put them in lower age groups.

For this reason and because of failures (in Italy it is possible to repeat the school year), almost half of teenage foreign pupils are lagging behind in school (Miur data 2020-21).

In this way, gaps widen. Many youngsters give up on their hopes and dreams, and potential talents are lost. Very often, they do not even make it to the final diploma: 30.1 percent of them drop out of school early (Eurostat 2022), compared to 9.8 percent of Italians.

Considering their needs, schools receiving migrants are poorly resourced. Italy's education ministry has a National Observatory for Integration, and extra funding is available for "high migration" areas. But second-language teachers are not normally employed in schools and there is a general insufficiency of teaching hours. School managers and teachers have to juggle between national and local funds if they want to guarantee at least some second-language teaching and other inclusion projects, with the support of outside parties and even volunteers. More resources are also needed for cultural mediators, anthropologists, psychologists, for children in difficulty and with traumatic experiences (especially those from war-torn countries), and to improve communication with families.

In the case of the UK, schools have a lot of autonomy and can apply for funds for EAL students. But then there is a lack of common standards for integration actions. In 2018, the Education Policy Institute (EPI) proposed introducing an additional fund to support late arrivals, but this was not followed up.

Schools such as City Heights are struggling to deliver a positive welcome and successful integration against a background of growing social deprivation and poverty. This affects not only communities, but teachers themselves. In the UK, teachers' unions have been mobilising since February, their members exhausted by heavy workloads and falling real wages.

Given the anti-immigration policies of the Meloni and Sunak governments, the future of migrant teenagers in both countries seems more uncertain than ever.

Supported by Journalismfund Europe

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!