This article is reserved for our subscribers

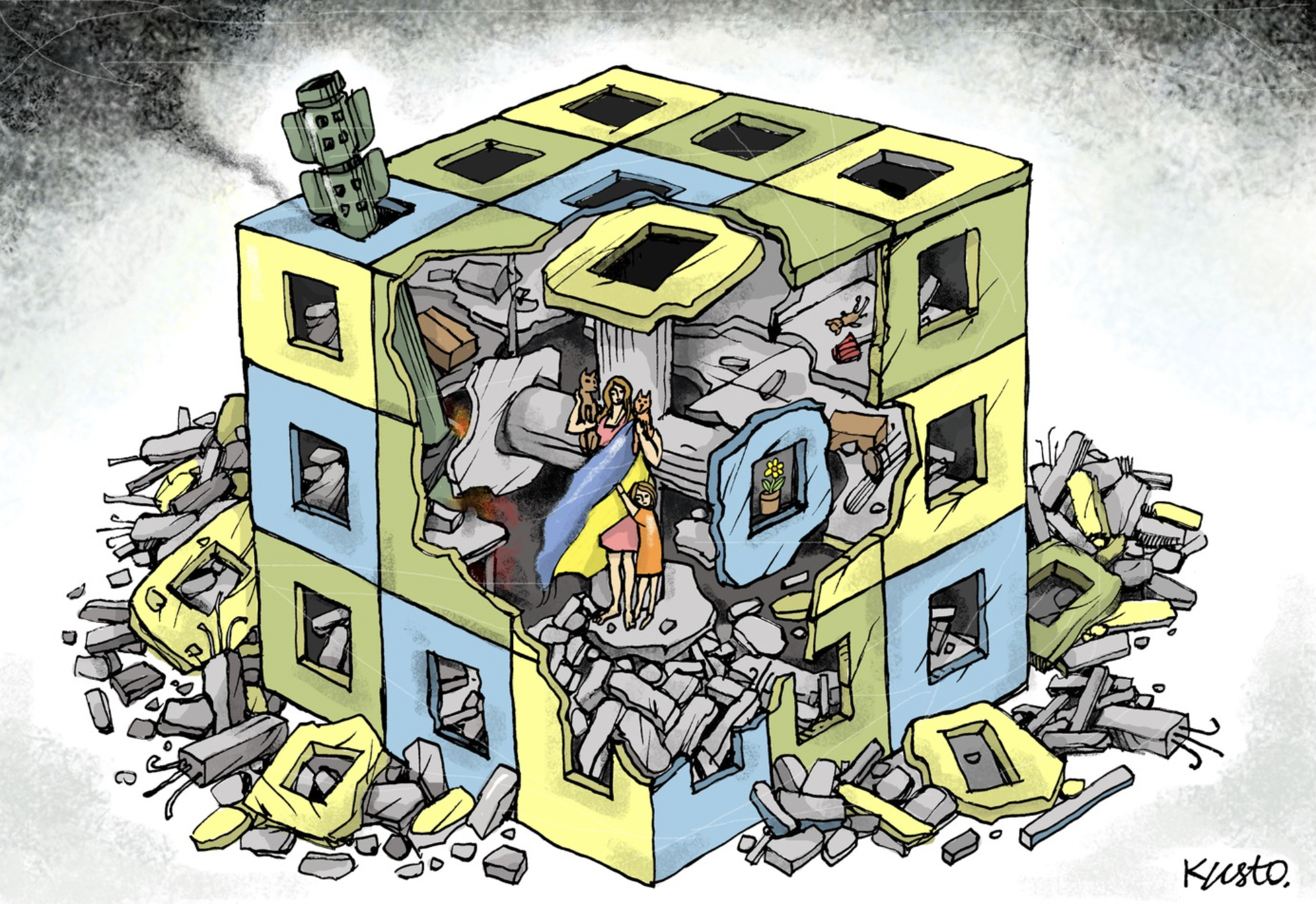

Kyiv, Ukraine – Most of those who have come to the Ukrainian capital during the last year have been surprised by how normal Kyiv life seems. Restaurants and cafes are full, all services are available, including entertainment; the city is bright, and the traffic is as bad as it used to be. Most people admire that, praising Ukrainian resilience. Others interpret it as a sign of happy-go-lucky attitude.

What one can say for sure is that the big Ukrainian cities are in no way back to normal, and they will not be in the nearest future. What an outsider sees is a new norm.

Looking over the shoulder of a young hipster in a popular café you may notice a drone flight simulator on his laptop screen: he just spent a few hours training. If you overhear conversations at the next table or on the street, there is a high probability that people discuss the developments on the frontline, or, again, drones or other military needs.

Not all people who serve are wearing uniform, especially those who are involved in intelligence, military tech, supply, or other defence branches. A guy at the next table may look like a DJ, but you don’t want to know what he knows.

Another aspect of the new norm is that daily life is adjusted to the permanent risks. On 7 February early in the morning, Kyiv was attacked, and the air defence shot down twenty missiles targeting the city. Five people died, and forty were injured. After the “all clear” signal, in one neighbourhood, firefighters and paramedics were helping the residents of the building hit by the debris, while the rest of the city was functioning as any other day: people headed to offices, children went to schools, and conferences started. Business as usual, just less sleep and more caffeine.

Contrary to the impression you get if you look at the coverage in the international news, the latest attacks on Kyiv were more severe than last year. The missile attack on Ukraine on 29 December 2023 was the deadliest in Kyiv since the start of the full-scale invasion. Other cities, such as Kharkiv and Kryvyj Rih, suffer constantly. During the massive attack on 2 January, unprecedented in scale, Ukrainian Air Defence had hit 72 missiles, including ten hypersonic ones; some people went to shelter at the metro stations (the usual and highly recommended practice), while others were using the same metro to go to work.

That’s how it works: even in the deadliest hours the city doesn’t stop entirely. Those who take their morning shifts and support the most important infrastructure just keep going. In Kharkiv, a business sends clients an apology for the several hours-long delay of delivery as their building was hit that morning.

It would be overly optimistic to uncritically project this attitude to the whole country. One can easily bump into the advertising of “legal services” for those who wish to avoid conscription, just as the voices branding it “unconstitutional.” Mobilisation is a painful, inconvenient topic: definitely not a good choice for a small talk; a hot potato for politicians, and a conflicting line in society in general.

It has highlighted a number of old issues, such as inequality, the problems of small towns and villages, the mutual stereotypes of different regions of the country, and many more. The Ukrainian Army enjoys enormously high trust in Ukrainian society, and that fact helps resisting Russia's obvious attempts to use mobilisation to disrupt the situation.

Waiting in uncertainty

However, the problem is there: people who spent two years in trenches deserve to be replaced and to return to their families. As the prospects of most of them are vague, the tension only grows, and it’s not a productive one. Waiting in uncertainty never serves a good debate.

Those strong voices, both sincere and amplified, are the most heard. But the general picture may be a bit different. In February 2024 less Ukrainians believe that the country is going in the right direction than those who think the opposite: 44% agree that Ukraine is on the right course contrary to 54% in December 2023. In February 2024, many people believe that things go south: 46% to 32% in December 2023. The trend may look chilling, but these figures are still better than before the invasion.

Ukrainians are more optimistic in the middle of the war than in pre-invasion years

No matter what you compare: the general evaluation of the course the country is taking, the self-estimation of one’s family well-being, the rating of the president Zelensky, Ukrainians are more optimistic in the middle of the war than in pre-invasion years. Compared to the survey results of the first months of the war (when only some occupied territories were liberated), the figures at the beginning of 2024 look grim. So what is the norm now? How much trust does a politician really need in wartime compared to in peace (even disrupted by COVID)?

The honest answer would be that no one knows as no one has experienced a 21st century full-scale war in a European country before. The coexistence of multiple realities is what makes Ukraine flexible and strong. However, it remains to be seen how fragile the balance between these realities is. And that would be another honest answer.