When creating their funds, asset-management firms make use of reference indices of companies, known as benchmarks. These indices are provided by rating agencies, and often do not take into account any environmental or social factors for the companies featured in the index. On the contrary: they regularly include oil and gas companies, which are highly profitable.

Europe's Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (SFDR) contains ambiguities that lend themselves to stretched interpretations. Eurizon, an asset-management subsidiary of Intesa SanPaolo, thus manages to propose "green" funds that have precious little green about them. It does this by using existing benchmark indices of companies which bear scant relation to environmental conservation or sustainability. This despite the fact that Eurizon – which manages client assets worth €381 billion – claims (in its sustainability report) to believe in a "financial humanism based on respect, responsibility, and awareness of one's own qualities". It turns out the scheme used by Eurizon is common among asset managers. Let us go through it step by step.

What are benchmark indices for?

How do you assess the general performance of a market – e.g. wind energy – quickly and easily? By compiling a benchmark index of that market, in which the various turbine manufacturers are present, with different weights. The larger companies will have a higher weight in the index and the smaller ones a lower weight. So if the profits of the larger companies increase, the index will show a higher growth value, while the performance of the smaller companies will have less influence on the value of the index.

An asset-management company that wants to build a fund that invests in the wind-energy market can therefore base the fund on a benchmark index that already contains a list of companies operating in the sector. Fund management is said to be "active" when the manager includes or excludes certain companies from the portfolio, according to his or her own criteria.

For a fund that wants to target firms with an "ESG" (environmental, social, and corporate governance) objective, one would expect to see an index containing companies operating in wind power or other such sectors with a positive environmental impact, or perhaps "de-carbonised" indices (which give more weight to less or non-polluting companies).

Eurizon adopts a different strategy. In the funds we analysed, it uses indices based on the oil and gas market to build its so-called "green" funds. Those indices include, in addition to socially and environmentally virtuous companies (as claimed by Eurizon), fossil-energy giants such as Eni, Enel, Repsol, Chevron, TotalEnergies, BP and Shell.

"These companies have an interest in being part of the portfolio because this way they will receive the increased funding usually attracted by funds classified as Article 8 or 9 [of the SFDR, that regulates 'green' financial products]. If they are in such funds, they receive more investment," explains Fabio Moliterni, climate and ethical-finance specialist for the financial company Etica SGR.

The SFDR imposes transparency criteria that asset managers and financial advisors must meet, as we explained in part one of our investigation. It distinguishes sustainable investments into two categories: those that merely promote "environmental and/or social characteristics" (Article 8), known in the jargon as "light green"; and those that must be truly "sustainable products" meeting more stringent criteria (Article 9), known as "dark green" (see our article).

How investments in Big Oil become (fake) green

Consider, for example, the fund "Eurizon Energy and Raw Materials". This investment vehicle is actively managed using the following indices: 50 percent MSCI World Energy; 45 percent MSCI World Materials and 5 percent Bloomberg Euro Treasury Bills. None of these indices are linked to ESG methodologies, as MSCI and Bloomberg themselves declare. MSCI is the rating agency that maintains 95 percent of the indices used by Eurizon to build its funds.

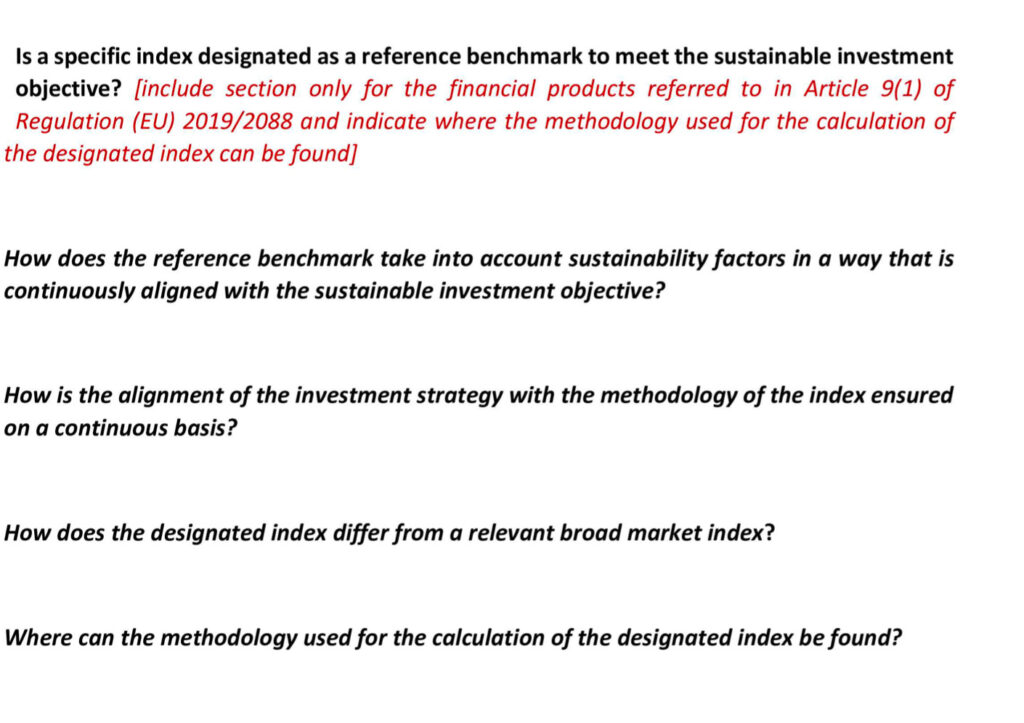

In its annual report Eurizon confirms that "no benchmark index has been designated for the pursuit of environmental/social product characteristics". Instead, Eurizon has established its own "green" index, thereby freeing itself from the specific requirements of the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA). This way it does not have to explain to investors how its benchmark indices guarantee that its fund pursues "environmental and social characteristics" (Article 8 of the SFDR).

It can do this by claiming to have deviated to a certain extent from the benchmark index – the above-mentioned "active" management – by adding more environmentally friendly companies to its portfolio that allow its fund to achieve socio-environmental objectives, or by removing others that are dirtier. The SFDR allows managers autonomy and flexibility in assessing these objectives. The rating is made by MSCI itself, which maintains the indices used by Eurizon, "based on its assessment of the environmental, social and governance profile of the companies it invests in". In Eurizon's annual report, that assessment indicates an ESG score of 6.95 (out of 10) for the fund it manages.

On the one hand, therefore, MSCI provides Eurizon with an index that is de-facto devoid of ESG criteria. On the other, it assesses and assigns a passing ESG grade to the Eurizon fund based on the same index.

The system is based on arbitrary parameters decided by the managers and the rating agencies, without control by public institutions. This means that even a fund that finances large CO2 emitters can present itself as green. In short, the referees are also the players, and they can adapt the rules of the game to their own needs. It is the same perverse mechanism at the root of the 2008 financial crisis, where the rating agencies that had to assess the quality of mortgages were paid by the same banks that issued them – a clear conflict of interest.

Thanks to this setup, Eurizon can claim that the fund makes 17.21-percent "sustainable" investments. Even this figure was obtained "according to the methodology adopted by the SGR" (the fund manager), as Eurizon itself points out. Eurizon does not even refer to the European taxonomy. Adopted in 2022, this is a sort of catalogue of green finance that lists the types of investments deemed sustainable by the EU. Investments in oil assets, such as those within the Eurizon funds, are naturally excluded from it. The SFDR does allow "sustainable" products that do not conform to the taxonomy, as long as the managers declare this fact. And indeed, in its annual report Eurizon notes: "The proportion of environmentally sustainable investments within the meaning of Regulation (EU) 2020/852 (i.e. aligned to the EU taxonomy) was estimated at 0 percent."

Green MEP Bas Eikhout judges that this room for manoeuvre in the regulations is excessive: "What is happening is that you are regulating the good part. This way those who do good have more regulations on their back than those who do bad. You can just say 'I am not taxonomy-compliant' and that's it, there's no problem. You just need to be transparent and then it's OK."

So the SFDR does not require fund managers to apply the taxonomy when classifying their funds as "sustainable". But the European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA) did tell us that, taxonomy notwithstanding, "any other sustainable investments must also not significantly harm any environmental or social objectives." In addition, Eurizon was required to calculate, based on the indicators stipulated in the regulation, the potential environmental impact of its investments declared as sustainable. The harmful activities to be considered are those specified in the taxonomy, as prescribed by the SFDR.

These include, for example, high emissions of CO2 and other air pollutants; biodiversity degradation; and water pollution. All of these things are associated with the extraction and consumption of hydrocarbons, the sector in which several of Eurizon's portfolio companies operate. Eurizon flouted this obligation when qualifying as "sustainable" (Article 9) products that instead merely promote "environmental and social characteristics" (Article 8). We explored this in the first part of our investigation. When challenged by us, Eurizon corrected the language used in its communications with investors, removing the description "sustainable and responsible fund" from its per-contract documents.

What the experts think

However, the lack of transparency on benchmark indices also calls into question the compliance of Eurizon funds with Article 8. Etica SGR's Fabio Moliterni explains: "If I choose a certain benchmark, it means I am adopting the same investment strategy. To do otherwise would not make sense." When we asked, MSCI did not want to provide us with the (non-public) documentation detailing the full composition of the index that Eurizon used as its benchmark. Thus the investor has to blindly trust the company about the ESG qualification of investments. In the view of Moliterni: "It is a problem of conflict of interest of the rating agencies. They have the power to give you the benchmark and rate products, but are not obliged to give full information on how the ratings are made."

When questioned, ESMA stated that "although the financial market operator offering this product may assert that it has not designated a benchmark for the purposes of achieving environmental and social characteristics, based on the information you have gathered it can be argued that it has done so". But, ESMA added, the "financial product may merit further investigation by the supervisory authority". It is therefore for Italy's National Commission for Companies and the Stock Exchange (Consob) to determine whether Eurizon needs to disclose the ESG methodologies used in the benchmark index on which it built its fund, as required by ESMA's standards. Given that the MSCI index does not incorporate ESG factors, Eurizon would risk finding itself with a fund that lacks any hint of greenery.

The ESMA also asserted that it does not believe that Eurizon's link to MSCI's website is sufficient to identify the methodology used by the rating agency. Indeed, for the Bloomberg index it uses, Eurizon provides a link that leads to a list of indices in which the one in question does not appear.

We therefore pressed Consob, but they did not answer our question about a possible investigation on their part, citing an "obligation of confidentiality".

Do too many rules end up harming investors? A possible reform of the European regulation is currently under discussion in Brussels. This may raise hopes of simplification, in the interests of clarity and the environment. Yet, as Dutch Green MEP Bas Eickhout observes, "the European Commission is hesitating and stalling by saying 'maybe we have done too much'. This is not really the lesson that should be drawn. Right now I think the sustainable finance agenda is failing. The need for an overhaul is not a priority for the Commission at the moment. What we see is that the Commission is really passive on sustainable finance, where the agenda is only getting started."

For its part, Eurizon has updated its sustainability disclosure in response to our reports. It now includes English-language explanations for all items that were previously left to the free interpretation of investors.

Supported by Journalismfund Europe

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!