Ayan (not her real name) was eight years old when her aunt asked her to go to the living room. Several women were sitting in a circle, waiting for her. “I didn’t know what they were going to do to me,” she says. “They told me to sit down and then my aunts sat behind me”: they held her head, shoulders, and neck still, while “two others held my legs,” she recalls. Without anaesthesia or painkillers, Ayan underwent a severe form of female genital mutilation (FGM). “I remember vomiting,” she continues.

They then tied Ayan’s legs together so that the wounds could heal. She remained like this, at her aunt’s house, for a week. Eventually a woman came to visit and said that some of the stitches needed to be redone. “My aunt told me she was doing it for me, for my future, because otherwise no one would marry me,” she recalls. The second time hurt even more. Ayan spoke about her experience with The Journal. It is, she says, a pain she will never forget.

| Female genital mutilations in Europe |

| Data from the European Institute for Gender Equality (EIGE) estimates that in Europe around 600,000 women and girls live with the consequences of genital mutilation, while another 190,000 are at risk of undergoing it, and the numbers are rising. In 2024, UNICEF recorded approximately 230 million girls and women worldwide who have undergone genital mutilation and survived. Female genital mutilation consists of the total or partial removal of the external female genitalia, and is usually performed on girls between the ages of five and eight in around 30 countries in Africa and the Middle East, as well as in several communities in Asia and Latin America. |

Ayan, a Somali refugee in Ireland, is now 23 years old. She arrived in Ireland in February 2025, seeking international protection. After undergoing FGM, she was forced to marry an older man and suffered violence and abuse. She fled Somalia to Greece and then to Ireland. What Ayan underwent was one of the most severe forms of genital mutilation. She has frequent urinary tract infections and requires surgery.

Surgery alone is not enough

There is no going back from FGM, but surgery can partially repair the damage and alleviate the pain. Nina Tunon de Lara welcomed me into her office at the André-Grégoire Hospital in Montreuil (a commune in Seine-Saint Denis, east of Paris), which specialises in this field. Tunon de Lara is the project coordinator for the hospital’s Réparons l’excision – Let's repair female circumcision – unit, created in 2017 by gynaecologist Sarah Abramowicz.

“According to the recommendations of the WHO and the French National Authority for Health (HAS),” Tunon de Lara explains, “isolated surgery does not make much sense, and good practice consists of integrating it into a multidisciplinary, comprehensive, personalised support programme tailored to the needs of all women.”

“Our goal is for all treatments to be covered by the national health system, so that there is no more isolated surgery,” Tunon de Lara says. Today, surgery forms part of the care to which a patient is entitled, which does not include psychological support, sexual medicine consultations, and other treatment. Every year, around one hundred patients from all over France undergo surgery in this unit: “Surgery makes sense when it is part of a process that allows the woman to come to terms with what has happened… because reconstructing a clitoris will not create sexual desire.”

“Today, it is possible to undergo surgery in clinics that do not specialise in treating women who have suffered violence, but this is not good practice, quite the contrary,” Tunon de Lara adds. In Montreuil, women who have undergone genital mutilation can benefit from multidisciplinary care that combined sexual medicine, psychology, discussion groups, and social assistance. The entire process is free of charge for those who access the service.

‘FGM is a specific phenomenon in the fight against violence against women. We want to give a voice to women who are victims of genital mutilation’ – Nina Tunon de Lara

Without such support, the procedure can end up reawakening traumatic memories, Tunon de Lara explains.

“Women who have gone through FGM, the first thing they will always remember is the cut", Somali-Irish activist Ifrah Ahmed tells The Journal. “Everything else is second, from becoming a wife to giving birth to your first child. They can still feel the scissors, they can still hear their sisters screaming, and they can still see the blood. It’s a horror.”

Female genital mutilation is only the first in a series of acts of violence, and this is what the Montreuil unit is trying to make clear. “FGM is a specific phenomenon in the fight against violence against women. We want to give a voice to women who are victims of genital mutilation, so that they are included in the continuum of sexual violence against women,” says Tunon de Lara.

“This continuum includes forced marriages, domestic violence of any kind (physical, sexual, psychological), or having to flee such realities via migration, which is often followed by administrative violence upon arrival in France, and even a period of living on the streets. Women who are victims of female genital mutilation – not all, but many – will suffer a great deal of violence, and genital mutilation is the starting point.” This is why, Tunon de Lara says, it has to be seen as part of the continuum of sexual violence, not as something separate.

Le Monde reports that in France, according to data from the Minister for Gender Equality, Diversity and Equal Opportunities, 139,000 women have undergone FGM, which consists of cutting the clitoris and sometimes the labia minora, and 28,500 girls are at risk of undergoing it. The Paris region is the most affected area, particularly Seine-Saint-Denis: 7.2% of women living in this department have undergone FGM.

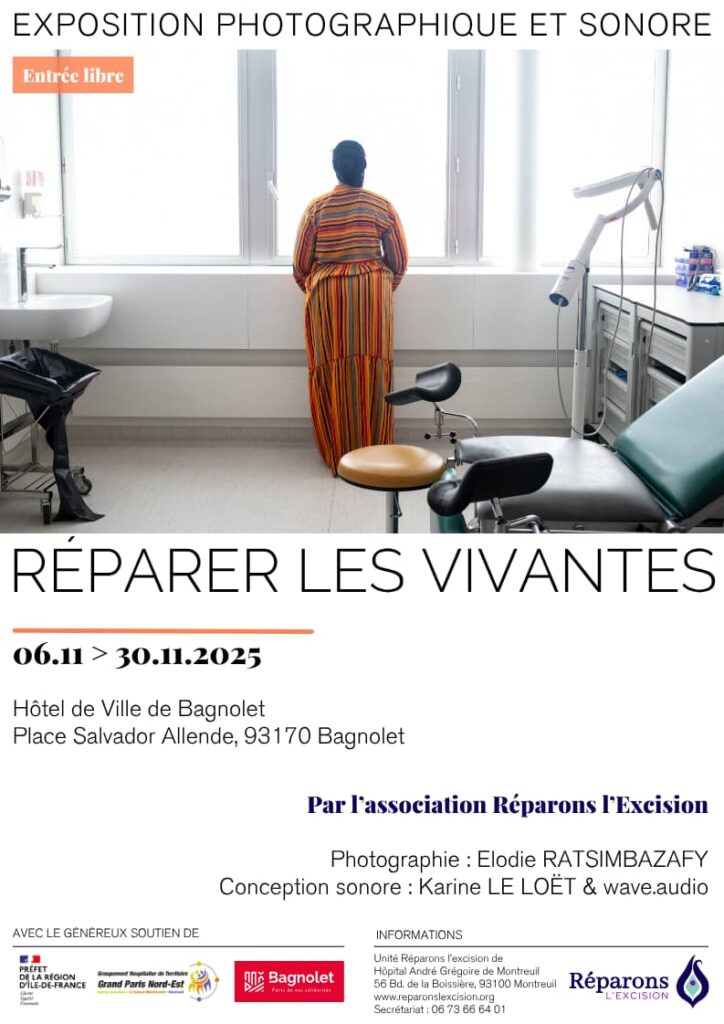

Réparons l’excision is a pilot project with a three-year trial period. If approved, it will become the model to be adopted around the country. The work of this centre is the subject of a photographic and sound exhibition created by Elodie Ratsimbazafy and Karine Le Loët.

The End FGM European Network has put together information, interactive maps, and campaigns on the issue. In their document “How to talk about FGM” they explain that FGM must be considered a violation of human rights and not a cultural practice, and that its perpetuation involves both men and women. “I think we need to be careful about the cliché of FGM and country of origin. FGM is not just an African problem,” says Tunon de Lara. “It also occurs in Asia, and I think it’s important to say that. It’s a transcultural, transcontinental, and transreligious phenomenon.”

| Other examples in Europe |

| In Dublin, the migrant women’s support group AkiDwA trains midwives, social workers, and teachers to recognise and report FGM. The FEM Süd centre in Vienna provides medical and psychological assistance, and trains healthcare professionals. However, according to a study by BMC Public Health, only 3% of women estimated to have undergone female genital mutilation have a medical file. Similar problems are also reported in other Western countries. The Dexeus Mujer Foundation based in Barcelona performs free genital reconstruction surgery for survivors. In Spain, the 2015 National Health Protocol establishes how professionals should identify and respond to FGM, but NGOs say implementation varies from region to region. |

🤝 This article was produced as part of a series produced thanks to the PULSE project, a European initiative supporting cross-border journalistic collaboration. Contributors include Patricia Devlin (The Journal Investigates, Ireland), Lola García-Ajofrín (El Confidencial, Spain) and Ann Wiener (Der Standard, Austria).

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!