Once there was a little café, Poni da Daini, on Zubalashvili Street in the centre of Batumi, Georgia’s second-largest city on the Black Sea. It offered sweets, cakes and coffee brewed in hot sand – Batumi-style. Indira Ebralidze, the owner, managed her small business alone and did not have to pay rent, yet still failed to make a profit. She was forced to close the café after a year. But the main reason, she says, was the growing number of Russian cafés in the neighbourhood.

“Actually, it couldn’t and didn’t work! Why? Because 90% of all cafés in the old part of Batumi belong to the occupants [Russia occupied 20% of Georgia after a short war in 2008]. Russian tourists know where to eat, as they receive the addresses by mail in advance… [Last year] the high season was a complete failure, I can say. If you manage to take home just enough to cover your rent or staff salary, there’s no profit! I was lucky I owned the premises… You can see for yourselves the place is wonderfully located, so why should I close it down?”

As we walked along the street, Indira stepped into several cafés and asked the price of coffee in Georgian. She received replies in Russian: Здравствуйте (“Hello”) Ничего не понимаю (I don’t understand), Я немного понимаю, но к сожалению пока плохо говорю (I understand a little, but sadly I don’t speak well).

The story of Indira’s café is just one example of the negative effect caused by the businesses opened by those Russians who had moved to Georgia.

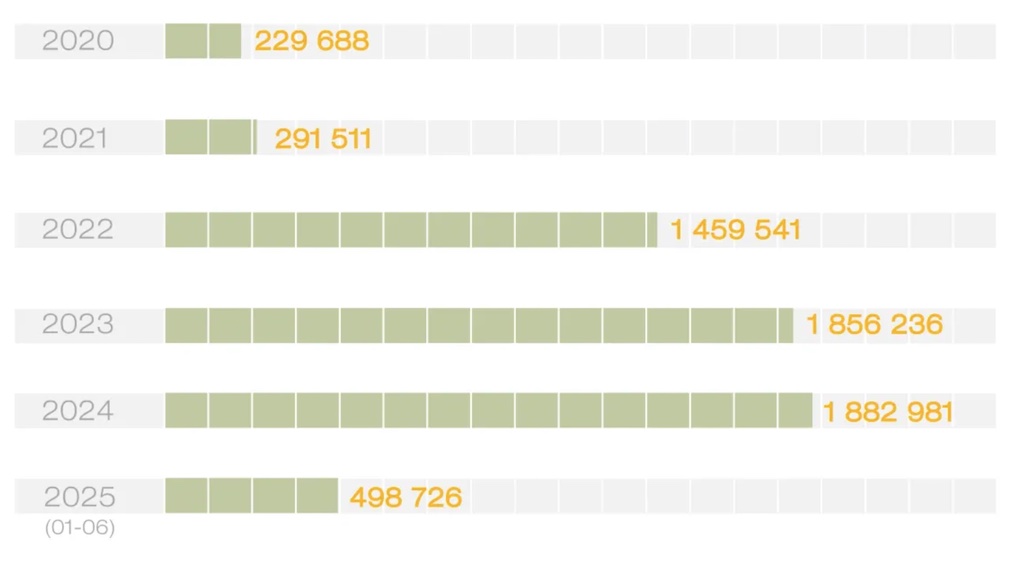

In spring 2022, Tbilisi’s mayor, Kakha Kaladze, described the Russians queuing at the Larsi Pass in the Caucasus as “tourists”: “We welcome the inflow of tourists… The authorities will do their best to support the trend. It is directly connected to economic growth, and to the increased number of workplaces, boosting employment…”

The reality, however, has proved quite different. Most Russian migrants register as individual entrepreneurs or small business owners and benefit from tax exemptions. While they have indeed created jobs, these largely go to fellow Russians rather than Georgians.

Russian Guides and Propagandists

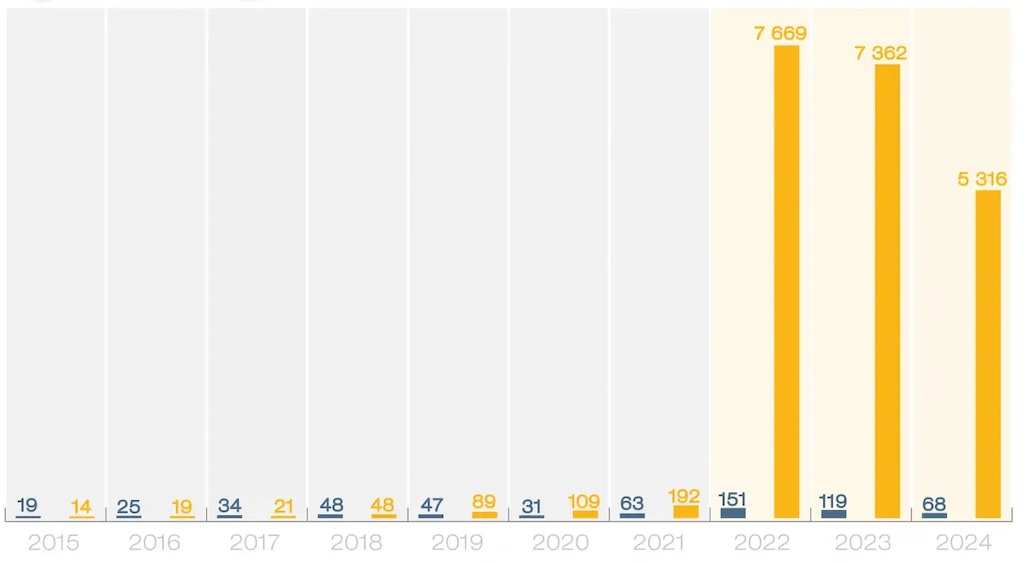

Seeing Russian tourists or Russian-speaking guides in Georgia is nothing unusual. They can be found everywhere – in Tbilisi, across the regions, on mountain trails and at seaside resorts. But since 2022, their presence has expanded dramatically.

Georgian guides in Tbilisi, Kutaisi and Batumi say Russian migrants rapidly took over their work and now control around half of the sector.

According to them, Russian guides create their own routes and promotional materials, operate both online and offline, and even open their own hotels. Beyond the financial impact, they warn of a more serious issue: Russian guides distort Georgian history, present misleading facts and omit any mention of the occupied territories of Abkhazia and Samachablo (South Ossetia) when speaking to tourists from Russia and Europe.

We spoke to Lela Gogava, Executive Secretary of the Certified Guides of Georgia. With 18 years of experience, she works in both French and Russian. She says the number of Russian guides has multiplied, and they employ only other Russians, leaving no need for Georgian guides or drivers. Russian tourists also prefer to hire them, which has severely reduced the income of local professionals:

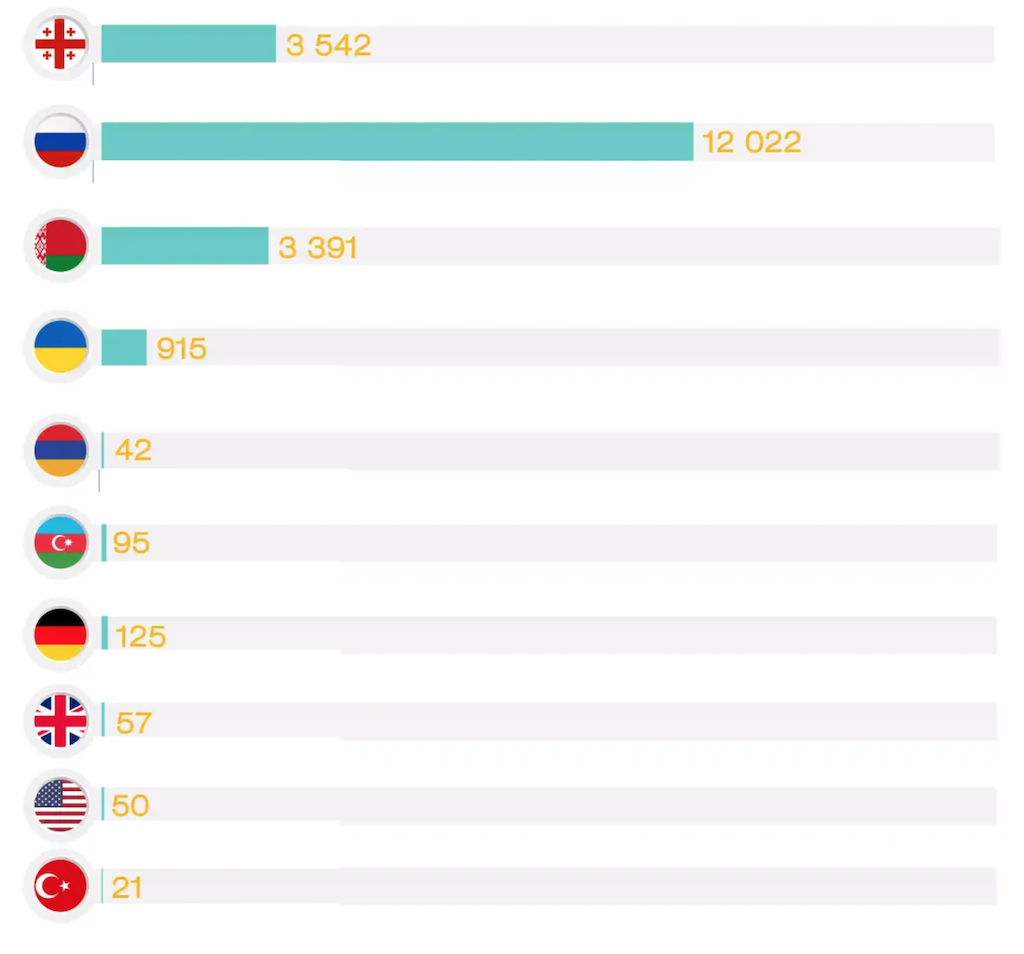

“Some hadn’t even worked as guides, but decided it was a rather lucrative job, so they took over the sector. They bring Russian-speaking visitors from Russia and Belarus… By the way, Ukrainians, Byelorussians, Turks and Iranians do the same – they often arrive with their own guides, but Russians outnumber them… The situation in Batumi is particularly dire. Many Russian-speaking Georgian guides have lost their jobs. Some of them worked with pilgrim groups, but now have less work because Russians bring religious groups themselves. […] The political turmoil has played a significant part because nobody knows whether we’re heading towards Europe or Russia. There surely are very few visitors from Europe. And all the while, the government says it’s all right because the Russian market is massive. The problem is that the Russians have completely taken over our market.”

Russian Businesses in the Tourism Sector

Visibly shaken, Lela adds that Russians are not just guides but also propagandists: “They don’t have the right information about the buildings in Tbilisi, so they invent their own stories and present Russia in an overly positive light. They talk about Russians' presence in the Caucasus as if nothing would have been possible without them…”

In Kutaisi, Russian-speaking guides Dali Chitishvili and Eka Tabagari, with 15 and 6 years’ experience respectively, say their workload has dropped sharply and their incomes have suffered.

“Compared to previous years, there is very little work; we aren’t as busy. When a Russian guide arrives, they come on a tour with us once, learn what they need, and then start working independently. I’m sure they’re not giving accurate information. When I had Russian tourists, I used to tell them about the 1801 annexation of Georgia, and they would say the term ‘annexation’ was inappropriate because Georgia had asked Russia for help. I explained that we did indeed ask for help against invaders, but never imagined our kingdom would be abolished. Now, who knows what Russian guides are saying? It’s not hard to imagine,” says Eka.

Needless to say, there is no way of monitoring what Russian guides say. Nor is there any accurate record of how many Russian guides or tour operators work in the country. They are not required to register “guide” or “tourism” as their primary activity, making their numbers impossible to track. There is also no regulatory framework for guiding: no certification or licence is required. Certified guides exist, but certification is voluntary and largely symbolic.

“No one has ever been stopped or fined for guiding a tour,” says Giorgi Dartsimelia, a board member of the Association of Georgian Certified Guides.

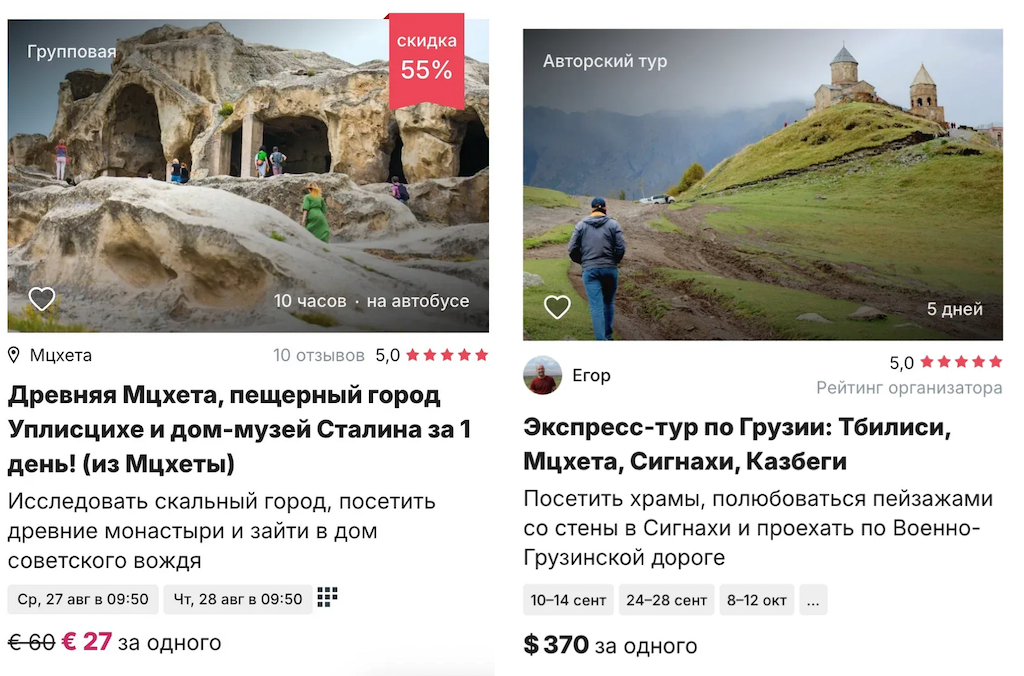

A further proof that the situation is completely out of control: Russian guides actively market their services through platforms such as tripster.ru, offering transport from Vladikavkaz in Russia’s North Ossetia and promoting “Sunny Georgia” to Russian visitors.

Hospitality business in Russian hands

In Tbilisi, walking up Zandukeli Street just off Rustaveli Avenue, the city’s main street, one encounters many attractive cafés and restaurants. One of them, the café Mariam Magdalene, once stood in a small cul-de-sac. It closed in 2022 and has since been replaced by David’s Garden, a café run by Russian nationals. It opened in autumn 2022, established by Vladimir and Anzhelika Khamzaev, Dementi Taradin, Pavel Dvurechensky and Yevgenia Grebenchikova – all recent arrivals from Russia. The Khamzaevs still own several businesses in Saint Petersburg.

David’s Garden is an Italian-style café offering hookahs and European cuisine. Initially, its Facebook posts were in Russian, but they are now only in Georgian and English – seemingly an attempt to appeal to local customers. Georgian influencers reinforce this strategy by visiting the café, sampling dishes and recommending the place on Instagram and TikTok.

Georgian restaurateurs and café owners say that the first wave of Russian migrants, shortly after the invasion of Ukraine, frequented their establishments heavily. Although some were uncomfortable with Georgian-language anti-war slogans and political messages on the walls, they still came in large numbers. Over time, however, Russian customers shifted to newly opened Russian-owned cafés and bars, which now serve mainly Russian clientele in both Tbilisi and Batumi.

“Initially, when they started coming to our bars, some of them were really rude. They objected to menus in Georgian, or to inscriptions insulting Putin, like ‘Putin Khuilo’. They were told they couldn’t expect everything to be their way, and soon their numbers dropped. They opened their own bars and created their own separate economy. At first the signs were in Russian, but now they use Georgian and English. It seems like a deliberate strategy to take over the entire market,” says Giga Tsibakhashvili, founder of the Tsibakha bar.

“When Russians first arrived, it clearly benefitted our restaurants and bars because they didn’t yet have places of their own. But they felt uncomfortable because we didn’t serve them in Russian. Now that they’ve opened their own businesses, tourists mostly visit their establishments. They have all kinds of restaurants: morning, daytime, evening cafés, Italian, French, Asian… They invested heavily in marketing and social media. As a result, they’ve pushed out many smaller Georgian establishments. They may be paying taxes, but that doesn’t help me,” says Keti Bakradze, a restaurateur and chef.

This trend is not based solely on the testimonies of chefs and bar managers. It is supported by research. According to Esma Kunchilia, Doctor of Cultural Studies and founder of the Georgian Institute of Gastronomic Culture, recent studies show that before 2022 Russian tourists relied on Georgian services – guides, transport, hotels and restaurants. Today, however, Russian-run services have replaced many of the Georgian ones.

“It’s an economy that doesn’t use the official state language, employs very few locals, and whose income largely leaves the country. The example of Batumi shows we are dealing with a ‘shadow economy’ marked by inadequate monitoring and regulation. Unfortunately, no one is discussing the real distribution of Russian capital in Georgia today,” she says.

The situation is made worse by the fact that many Russian businesses do not file financial reports. On the state reporting portal we found 13 Russian-owned restaurant businesses that had been officially warned for submitting incomplete or overdue reports. All were registered in Georgia between 2022 and 2024.

We asked the Georgian National Tourism Administration what measures are being taken to address the issue and support Georgian guides. So far, there has been no response.

Fake Economic Growth

“Why should we close the border? It’s not clear why we should be the first to do it,” Georgian Dream MP Aluda Ghudushauri said three years ago, insisting that income from Russian migrants would be closely monitored.

But after the promised “control”, Russians who settled in Georgia quickly established their own diaspora networks. They opened cafés, bars, beauty salons, schools, kindergartens, travel agencies, trading firms and warehouse services, much of which evolved into direct trade with Russia – benefiting Russians far more than Georgians.

“The only benefit for Georgia is that they might spend some of their revenue locally, while Georgians don’t earn anything and the state collects almost no tax… Russians have identified every legislative loophole and pay extremely low taxes, or none at all. They enjoy tax relief, employ their compatriots, and trade among themselves. On paper it looks like economic activity, but the actual beneficiaries are Russians themselves,” explains economist Giorgi Khotivari.

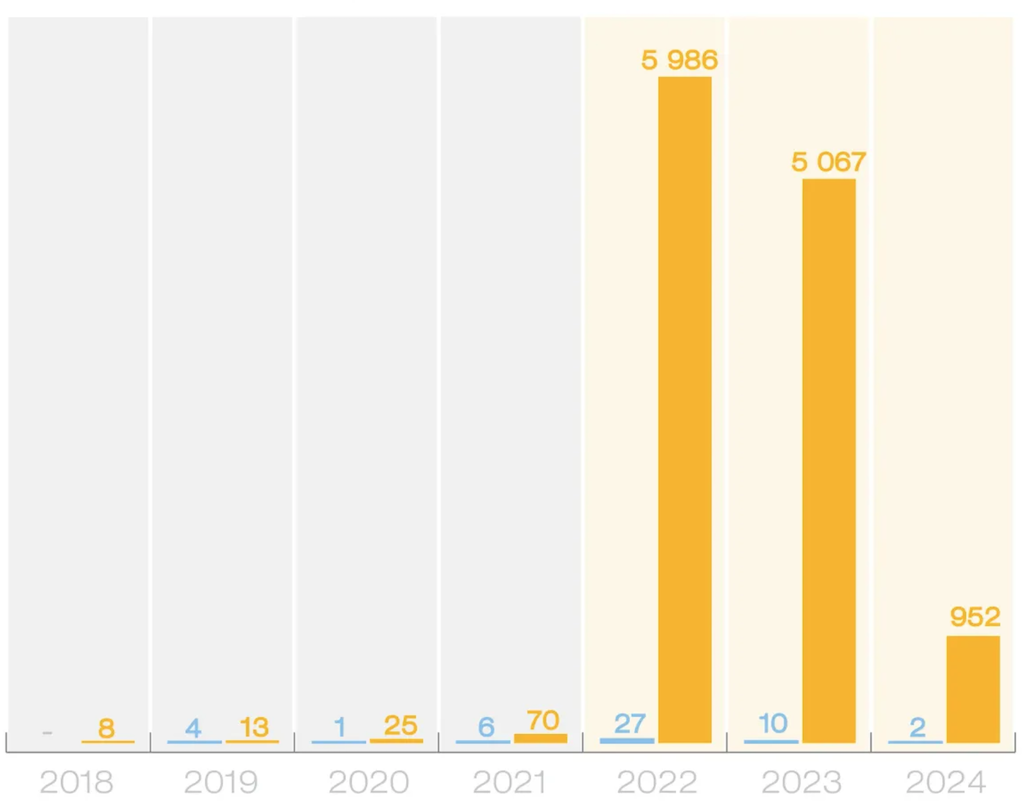

More than 20,000 Russian small businesses have been registered in the past three years. This means that instead of the standard 20% tax rate, most pay only 1% or 3% on their income.

We attempted to determine whether Georgia’s economy has genuinely benefitted from the influx of Russian migrants by requesting information from the State Revenue Service. We asked for a list of Russian business entities and the taxes they have paid since 2022. The request was denied on the grounds that the information was confidential.

Georgia – the Russian IT Heaven

Thanks to generous tax incentives, Georgia has become a highly attractive destination for Russian IT specialists, especially since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Today, of the 21,040 IT companies operating in Georgia, 57% are Russian-owned.

IT companies can register under two special categories – “international company” or “virtual zone” – both offering significant tax exemptions.

IT companies registered in Georgia enjoy two types of relief: those of international companies and those coming under the virtual zone status. [Translator’s note: special tax status introduced by Georgia to attract international IT companies by offering significant tax exemptions.]

Under these schemes: employees of an international company pay 5% income tax instead of the standard 20%; the company itself pays 5% profit tax instead of 15%; eligible companies are exempt from property tax (except land); companies under the virtual-zone regime also receive exemptions from export duties and VAT when providing services abroad.

The “international company” status is granted only after two years of activity and is reserved for firms serving clients outside Georgia. The “virtual zone” status applies to IT companies that provide digital or programming services to foreign markets.

One example is LLC JettyCloud, founded by Russian citizen David Slonimsky on 10 March 2022, just two weeks after Russia’s full-scale invasion. Slonimsky previously ran two IT companies in Saint Petersburg, closing both in 2020. Relocating to Georgia proved highly profitable. According to Forbes Georgia (2025), JettyCloud ranks 22nd among the 100 most valuable companies operating in the country.

In 2023 the company recorded ₾51 million (€16.25 million) in revenue, including ₾36 million in net profit, while paying only ₾1.3 million in taxes – almost certainly due to its virtual-zone status.

The Georgian Dream government has made the environment even more favourable: in June 2023 it hastily introduced simplified residence rules allowing foreign IT specialists to obtain a three-year residence permit, renewable four times. Officially, the aim is to make Georgia attractive for IT talent, ultimately boosting the national budget.

However, the Institute for the Development of Freedom of Information (IDFI) argues that this policy may serve less to promote the IT sector than to artificially sustain economic growth.

Queues of Russian Nationals at the Larsi Pass

Web developers and digital-transformation experts warn that many Russian IT specialists are likely paid in cryptocurrency, which is neither traceable nor regulated. They also highlight security risks.

“They don’t pay taxes to justify their presence in Georgia, nor do they produce anything for our market,” says web developer Giorgi Nakaidze. “They use our resources while serving American or British companies. Like in the hospitality sector, they employ their compatriots and create a tight-knit group. Unless you are an outstanding expert with a niche specialisation, you have no chance of being hired. […] When I worked with state organisations, we pushed to ban Mail.ru. Today, Russian programming services are thriving, which is dangerous. If needed, the FSB could get access with a single click.”

The government has little capacity to determine the real intentions of Russian nationals arriving since 2022, which poses a national-security challenge. Security specialist Andro Gotsiridze says the influx of Russians is part of the wider “hybrid war” Russia is waging across its neighbourhood.

“Russian money comes with strings attached, because it makes Georgian businesses dependent on Russia again… Remember 2005–2006, when Russian bans devastated Georgian wine producers”, he recalls. “Russian finances are always followed by Russian rules: assassinations, criminal wars, racketeering, merging state institutions with criminal networks – everything we see in Moscow and Saint Petersburg. This problem will become a growing cancer for any future government.”

👉 Original article on iFact

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!