Eventually, Tjeerd made it: after being runner-up in previous editions, the Dutch press cartoonist was awarded the European Cartoon Award on 12 December. The ECA tribe gathered on one of the top floors of Richard Maier’s splendid Central Library in The Hague for an afternoon dedicated to press cartoons and freedom of speech. The library also hosted an exhibition of press cartoons dedicated to the Award.

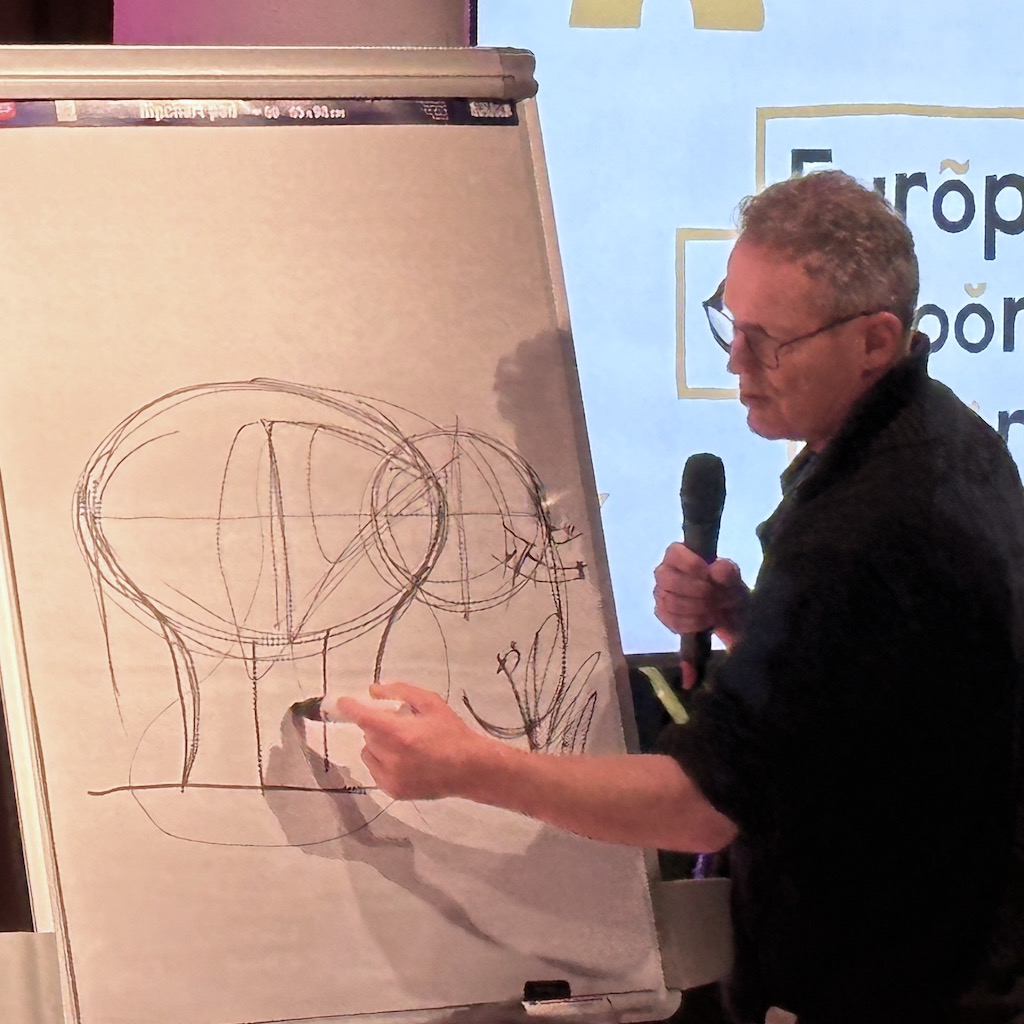

Tjeerd and his fellow runners-up, Zehra Ömeroğlu from Turkey and Emad Hajjaj from Jordan, were also present. They took part in engaging panel discussions while Maarten Wolterink ran a workshop on drawing political cartoons and one on drawing.

Cartoonists under pressure

In a wide-ranging discussion, Zehra Ömeroğlu, KAK (press cartoonist and president of Cartooning for Peace) and Emad Hajjaj described how satire was increasingly treated as a security threat – not only in authoritarian regimes, but also in countries that still called themselves democracies.

For Zehra Ömeroğlu said repression was both judicial and psychological. Although she had been briefly acquitted in June, her case – she was accused of “obscenity” for a cartoon on Covid – was swiftly sent to appeal. “It started all over again. So it’s still ongoing and I have no idea how long it will last,” she said. She was then based temporarily in Amsterdam and described returning to Turkey as “very risky”, as arrests could happen arbitrarily, even at the airport.

Beyond the personal toll, Ömeroğlu stressed the broader destruction of Turkey’s satirical ecosystem. Once a “paradise for cartoonists”, the country now had almost no independent platforms left, and her own magazine, LeMan, is regularly targeted by the judiciary. “There’s no media to publish my cartoons in my own language,” she said. Her response had been to turn her experience into an autobiographical graphic novel that kept a satirical tone despite the threat of prison: “It’s my way of coping.”

Emad Hajjaj recounted a similar trajectory, beginning with his decision in 2000 to portray King Abdullah II – something previously unthinkable in Jordan. Although the cartoon had been well received by the public, Hajjaj was fired months later. “Some powerful people up there didn’t like the idea,” he recalled.

His situation worsened after the Danish cartoon crisis, when religious sensitivities hardened across the region. Hajjaj faced lawsuits and threats for portraying Jesus Christ in a political cartoon. “I ended up spending months in court, just defending my right as a cartoonist,” he said. In 2020, he was arrested under Jordan’s anti-terror laws after sharing a cartoon critical of the UAE–Israel normalisation deal. “My charge was violating anti-terror laws… I was treated as a terrorist because of a cartoon,” he explained.

For KAK, who also runs the Cartooning for Peace ngo, these stories were part of a global trend. Monitoring threats to cartoonists worldwide, he noted a worrying shift: “The new thing is that the dots are lighting up in democracies.” In the past year alone, his organisation had documented serious cases in the United States, India and Turkey.

KAK argued that modern repression often operated through vague, malleable laws. “They create new laws that are easy to twist,” he said. Accusations such as spreading fake news or collaborating with enemies allowed governments to criminalise dissent while maintaining democratic appearances.

All three speakers stressed that cartoons were among the most peaceful forms of expression. “We don’t have AK-47s. We just grab a pen,” Ömeroğlu said. KAK added that satire undermined fear: “You draw them as clowns, and suddenly the fear doesn’t work anymore.”

Yet, as disinformation, social media harassment and legal pressure intensified, the speakers warned that the space for satire was shrinking worldwide — with consequences that went far beyond cartoonists themselves.

Je suis Charlie, 10 years after

This edition of the ECA was particularly significant as it marked ten years since the terrorist attack on Charlie Hebdo in Paris, in which 12 people, most of them cartoonists, were killed. Belgian journalist Isabel Junius presented the documentary that she had filmed on that occasion.

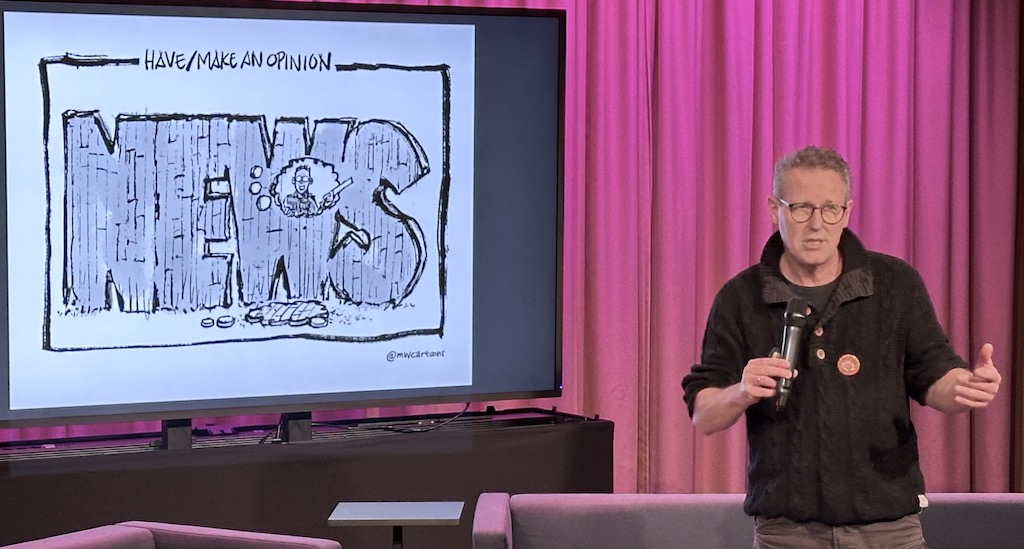

In another panel, American author Melissa Chan and Tjeerd discussed how political cartoons can amplify dissent, build community, and hold power to account – while also grappling with credibility, polarisation, and the economics of making satire survive.

Chan described her collaboration with exiled Chinese activist-artist Badiucao, whose social-media cartoons during the Hong Kong protests were designed to be printed and carried into the streets. She framed his work as an attempt to be “a voice for 1.4 billion people” who cannot speak freely, and noted how his focus has broadened from Xi Jinping to the rise of authoritarianism and the “decline of American democracy”, with Trump increasingly central.

Tjeerd argued that political cartooning is inseparable from taking a stance: “I couldn’t be a political cartoonist if I didn’t voice my opinion.” He saw success not as persuasion but provocation: “A cartoon is good if it starts a debate.” While social media once expanded audiences, he warned that platforms now impose opaque censorship and, more importantly, offer no viable income: “There’s an economic model for the Musks and for the Zuckerbergs… but there’s no economic model for cartoonists.”

Both stressed that democracy suffers when satirists cannot work professionally. As Tjeerd put it, autocrats “work 80 hours a week” – while underpaid artists must juggle other jobs. On AI, he was less worried for himself than for younger creators and the future “professional class of political satirists”.

On process, Tjeerd described a tight, audience-tested workflow: pick the issue that “makes me most angry”, decide the message, then find the visual – aiming for a cartoon “understood within a matter of seconds.”

Tjeerd and attorney Luisa Fernanda Isaza-Ibarra then ran a workshop on where to draw the line between satire and legality. They displayed some cartoons that had been subject to court rulings for allegedly crossing this line and asked the audience whether they thought the cartoons were inappropriate. They then showed the court rulings. Unsurprisingly, the audience's views were slightly more liberal than those of the judges.

Tjeerd and Luisa Fernanda Isaza-Ibarra. | Photo: ©PhotograVera

And here is the happy winner and runner-ups, Tjeerd, Hajjaj and Zehra with their respective cartoons (Photos by ©PhotograVera)

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!