Across European supermarket shelves, iconic products from global brands are increasingly marketed with “zero waste” pledges, often echoed in media headlines. In our “responsible” shopping basket items include Magnum ice-cream, Kind chocolate, Philadelphia cheese, Beanz beans, Nivea body care, Delizio coffee and rigatoni pasta.

The companies producing these popular goods proudly display claims of low-emission, recycled-plastic packaging on their websites. They are the UK-based Unilever, Mondelez, Mars and Kraft Heinz (US), Nivea (Germany), Delica (Switzerland) and Garofalo (Italy/Spain). On the surface, their statements look like good news for both the environment and consumers trying to make the right choices.

But reality looks different – and is just one click away.

The web pages presenting the products show that behind the green claims made by these companies lies the merchandising power of oil giant Saudi Aramco, through its plastics manufacturing subsidiary SABIC. Digging deeper, our investigation found that the Saudi firm’s “sustainable” recycling programme appears driven more by profit than by science.

SABIC, along with all other oil and chemical majors, promoted its plastic products as “circular” and climate-friendly. However, in practical terms, they remains almost entirely fossil-based, our investigation reveals.

Behind recycled packaging claims: Saudi Aramco

Aramco is the world’s largest single man-made contributor to climate change, responsible for more than 70 million tonnes of greenhouse-gas emissions (GHG) up to 2023 – a volume surpassed only by the USSR and China. Saudi Arabia’s state-owned major is also a strenuous opponent of EU and international efforts to solve the plastic crisis.

In Europe, about 30 million tonnes of plastic waste are collected every year. But 84% of that does not find its way back into new products and is landfilled, burned, or leaking into the environment. Over half of it comes from packaging.Globally, recycled plastics represent just 6% of total production, while 94% is virgin fossil-based resin which makes a 3-5% contribution to GHG emissions (mostly from energy consumption).

As the use of fossil fuels for energy gradually declines and is replaced by renewables, plastics, which are a petroleum derivative, are set to become the most lucrative business for oil majors, which dominate production through direct access to fossil raw materials. Plastic demand responsible for 95% of the growth of oil consumption between 2019 and 2024, is expected to grow, driving oil extraction from 2026 onward, according to the International Energy Agency.

It is not surprising that SABIC has been trying to lobby to weaken the UN Global Plastics Treaty, saying it did not approve limits on production (as revealed by closed-door institutional meetings) and pushing industry-friendly recycling solutions alongside ten other petrochemical companies that are members of the Alliance to End Plastic Waste.

Why, then, would reputable consumer product makers choose such a controversial ally to make and promote their sustainable packaging? Our investigation shows how Aramco via SABIC and its fellow Big Oil club members present appealing figures of high recycling rates and low emissions for brands eager to attract customers.

Chemical recycling and the pyrolysis promise

SABIC produces polypropylene and polyethylene, two synthetic materials used for packaging. Production occurs via pyrolysis, the most widespread chemical – or advanced – recycling process (the other most popular technologies are gasification, depolymerisation, and solvolysis).

To understand how this recycling model works in practice, it is necessary to follow the supply chain. Aramco’s chemical arm partners with the UK-headquartered Plastic Energy, sponsored via the investment firm LetterOne by Russian oligarch Mikhail Fridman, who was sanctioned following the invasion of Ukraine.

Plastic Energy, a formerly Spanish start-up, operates the recycling facilities which thermally decomposes plastic into feedstock – so-called “pyrolysis oil” – supplied to SABIC’s steam-cracking plants. These gas-powered, high-temperature furnaces break the input compounds into molecules called monomers, which are then linked together into the diverse polymers commonly known as plastic.

This process underpins the environmental claims now reaching consumers. Like the other 14 top petrochemical firms we investigated – together accounting for over half of Europe’s market share – SABIC promotes itself as “the solution” to closing the loop and curbing plastic GHG emissions.

How carbon savings are calculated – and inflated

But the data behind these claims tell a different story. Yet the evidence is questionable. In its carbon-footprint calculations (Life Cycle Assessment – LCA), SABIC admits that its plastic-recycling process emits 6% to 8% more than producing plastic from virgin oil.

To improve the numbers, the study relies on a common tactic adopted by companies riding the chemical-recycling wave: subtracting the emissions that would have been released if the same volume of waste had been incinerated. This delivers an apparent saving of around 2 kg of CO₂ per kilogram of recycled plastic.

SABIC’s LCA claims a “rigorous critical review” by a panel of experts including Carlos Monreal, co-founder of Plastic Energy – SABIC’s main feedstock supplier – and Sphera, a consultancy firm with a pro-industry record. Sphera authored Plastic Energy’s own LCA study, on which SABIC bases its assumptions and conclusions. The close business ties between the reviewers and SABIC raise questions about the degree of independent oversight and the impartiality of the review process. Both studies were carried out in 2025.

We asked experts to analyse Plastic Energy’s methodology summary (the full version is not public), under condition of anonymity. They pointed at inaccurate recycling rates and biased comparisons with incineration. The questionable 78% GHG-reduction claims are reproduced in SABIC’s study. Both companies declined to comment.

“LCA documents serve no purpose other than advertising, because the companies can control the parameters in a favourable way and achieve the results they want,” said Peter Quicker, Emission Control in Waste Management Professor at Aachen University, in Germany. Research confirms that LCAs can be selectively framed, masking the real climate footprint, based on the method and assumptions considered..

“What matters is not hypothetical emissions from incineration that are ‘avoided’ on paper, but what is actually emitted,” Helmut Maurer, former Senior Expert in the Environment Department of the European Commission, told Voxeurop “The CO₂ savings narrative assumes that, without chemical recycling, the waste would have been burned rather than being repurposed through mechanical recycling, which is not necessarily true.”

Why chemical recycling boosts virgin plastic production

Other recycling methods already exist – and perform better. Mechanical recycling is a cheaper and cleaner solution. It sorts, washes, and shreds plastic waste into flakes to make new materials. It does not alter the material’s structure through energy-intensive steps, which cause chemical recycling to emit up to nine times more GHG – thus eroding its advantage over incineration.

“Low-quality pyrolysis oil is often burned, and in those cases direct combustion of waste for energy recovery would be more efficient, with a better CO₂ balance,” said Stefano Consonni, Professor at the Department of Energy at the Politecnico di Milano university.

Potential CO₂ reductions highlighted by some studies may largely disappear when carbon-intensive electricity used to power pyrolysis is properly accounted for and when recycled feedstock replaces only a small fraction of fossil-based plastic. Which seems to be precisely the case.

Indeed, pyrolysis oil is highly corrosive to be used on its own and, as industry documentation (Total Energiess) confirm, can make up at most 5% of total feedstock (or 20% with advanced upgrading), requiring dilution with 80–95% naphtha to avoid damaging steam crackers. Moreover, only 10% to 50 % of pyrolysis oil is converted into monomers, as most is lost during feedstock refining.

Public records suggest that the recycled material or pyrolysis oil used by Sabic to produce plastic (2,600 tonnes in 2022) may represent even less than 5% of the total feedstock, given the huge quantity of naphtha (4 million tonnes) that the company fed into its European crackers in the Netherlands.

In practice, this dependence on fossil inputs is substantial. Hence, assuming a total feedstock of 20 tonnes, per each tonne of recycled component (5%), companies need to add 19 tonnes of naphtha (95%) derived from fossil oil. “The whole process is falsely labelled as plastic recycling, although globally, fossil-fuel use expands because virgin feedstock must be added,” said Maurer.

“The industry and oil-producing countries push chemical recycling to preserve plastic growth and fossil profits,” Lee Bell, technical and policy adviser at the NGO International Pollutants Elimination Network (IPEN) told Voxeurop.

Such a trend may jeopardize efforts to curb global carbon emissions: as expert Helmut Maurer told Voxeurop, “Plastic production could rise to between 1.2 and 1.6 billion tonnes per year and by 2050 plastic alone could consume a huge share of the carbon budget that is left before we exceed a global temperature of 1.5°C, the no-return threshold set by the Paris Agreement.” The climate impact is not the only concern. The Saudi government, which controls 15% of the world’s oil reserves, attempted to have this technology recognised as environmentally sound under the Basel Convention on the control of transboundary hazardous wastes, but the effort was rejected.

In addition, the pyrolysis method also has an environmental impact: “Pyrolysis oils are heavily contaminated with additives. They can release dioxins and other persistent pollutants that affect people’s health. Iit makes little sense to turn waste into hazardous waste,” said Lee Bell citing his report.

Chemical recycling Vs Plastic Re-usability

Despite these concerns, industry influence remains decisive. “Mechanical recycling must be preferred wherever possible, but where thist is not feasible, chemical recycling has a complementary role to play,” said Alexander Röder, Plastics Europe’s Director of Climate & Production Together with the European Chemical Industry Council (Cefic), Plastic Europe forms the industry’s Brussels-based lobbying stronghold. The two organisations represent major oil companies and plastic producers, including SABIC. Mark Williams, vice-president for Europe and a strong opponent to the Green Deal, sits on the boards of both organisations.

Röder cites mixed plastics as an example of a hard-to-recycle waste stream and points out that current EU legislation restricts mechanical recycling of food-contact packaging due to contamination risks.

However, his arguments are challenged by NGOs, who are urging the industry to make primary food packaging free of toxic additives and reusable. This would avoid contamination in mechanical recyclates and reduce the need for new plastic production.

This is the path followed by Ella’s Kitchen, a producer of organic food for children, and a former client of SABIC. According to Patrick Cousens, Board Director of PLMR, a public relations consultancy workingon behalf of Ella’s Kitchen, “In 2022, we worked with SABIC on a [...] time-limited trial [...] using a small amount of food-grade recycled content in our pouch caps. Since then, our packaging efforts have focused [...] on transitioning our flexible packaging to mono-material structures to improve recyclability at scale.”

Furthermore, a Europe-wide collaboration has recently achieved proof of concept for the conversion of polypropylene-based soft plastic films from supermarkets and household waste into food-safe recyclates. Plans are in place to integrate polyethylene. Authorisations from the relevant authorities are pending.

SABIC’s TRUCIRCLE® portfolio shows a narrow focus on reusability and mechanical recycling, while prioritising its chemical recycling business.

So far, SABIC has processed Plastic Energy’s feedstock through its steam-cracking unit in the Netherlands. Last year, the two companies shipped the first large-scale batches of chemically recycled plastic through their new joint venture facility. SABIC also partners with TotalEnergies in Saudi Arabia and BP in Germany, although Plastic Energy is not mentioned in the latter case.

The Saudi company is attempting to reduce plastic production greenhouse gas emissions by using electrically heated steam cracking, but this has not yet been scaled up beyond the demonstration stage initiated with BASF in Germany.

On its end, Plastic Energy also supplies pyrolysis oil to other major petrochemical groups, including Exxon Mobil, Total Energies and UK’s INEOS. In 2024, the latter launched snack packaging it claimed was made from 50% recycled waste, which PepsiCo uses to wrap its popular Sunbites.

Large multinational retail brands sell consumer products wrapped in SABIC/Plastic Energy recycled packaging in Europe, reaching millions of unaware shoppers as they roam the stores. These brands include the France-headquartered Carrefour, Coop (Italy) and Tesco (UK).

The latter has decided to collaborate with SABIC as part of its soft-plastics recycling programme, launched in its British stores in 2021. Tesco collects packaging from customers, which Plastic Energy and SABIC recycle into new plastic pellets. These are turned into Heinz’s Beanz microwavable Snap Pots, winners of the Environmental Packaging Award, by packaging leader Amcor/Berry International. These pots can be returned and recycled repeatedly. Tesco claims that its packaging contains 30% recycled material and that its carbon emissions are 25% lower.

Meeting the EU recycling targets with a failed technology

Many other brands are launching eco-marketing initiatives in an effort to attract consumers before more stringent EU and UK rules come into force this year.

The EU Single-Use Plastics Directive (SUPD) covers ten types of disposable products, including food containers, cups, beverage bottles, plastic bags and wrappers. Initially, it requires 25% recycled content in PET (polyethylene terephthalate) beverage bottles by 2025 and 30% in all bottles by 2030. The European Commission will gradually extend these requirements to other items.

Meanwhile, its Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) introduces broader recycling targets for all companies selling products in plastic packaging: These are set at 30% by 2030 and up to 65% by 2040. Member states must enforce compliance.

According to a European Commission study, chemical recycling is considered necessary in order to meet the proposed targets, given that the current plastics are not easily reusable and mechanical recycling alone cannot supply sufficient high-quality materials for sensitive food-contact applications.

The gap between promises and performance is widening. Currently, only 0.1% of total plastic waste in Europe is treated by chemical recycling, compared with 13.2% by mechanical recycling. Its current capacity is just 150 kt, accounting for only 1% of the total 13 million tonnes, and increasing this could take as long as 50 years.

Despite the success portrayed in SABIC’s public-relations communications, this technology has so far shown a record of failure due to high economic costs, technical inefficiencies, and environmental burdens.

Plastic Energy, SABIC’s associate, is a prime example of these failures. The self-proclaimed “global leader” promised to build ten plants in Europe to convert 300,000 tonnes of plastic waste into feedstock. However, only the plants in Seville and Almería are operational. Other projects in Spain and abroad have been delayed, scaled down, or cancelled, despite receiving €30.5 million in subsidies from the Spanish government (as reported by Público) and raising €277 million from private investors by 2024.

“Most pyrolysis […] plants I’ve seen over 25 years have failed or stalled, and large-scale, proven plants essentially do not exist,” said Milan Politecnico’s Stefano Consonni. “After decades of failure, we must question why this path is still being pushed.”

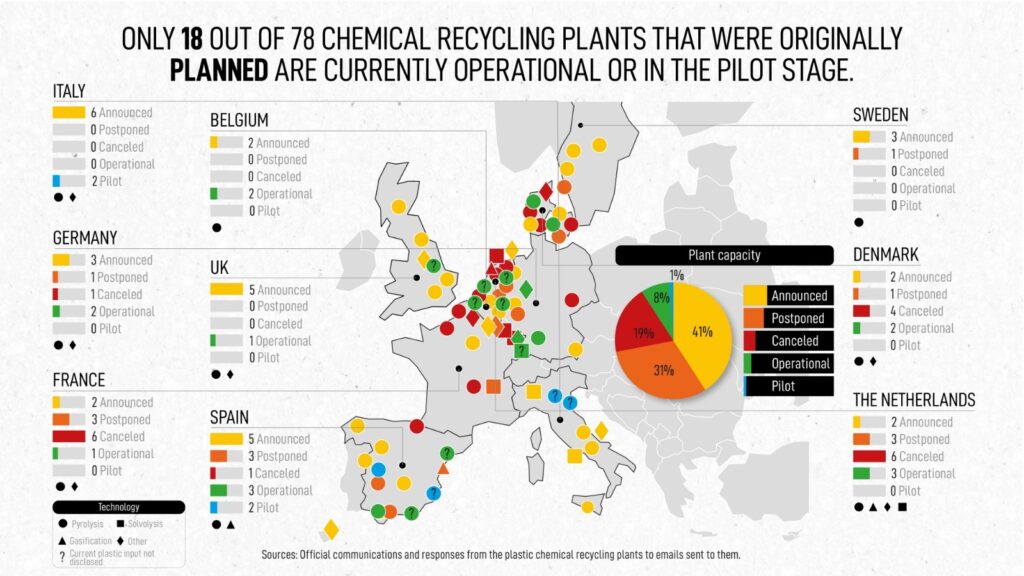

Of the 78 plants announced in Italy, France, Spain, Germany, the Netherlands, Denmark and Sweden, we found that most have been cancelled or delayed. Only 18 are operational, three of which are still in the pilot phase. These plants are processing just 0.24 million tonnes, compared with the planned 2.9 million tonnes. In 2025, three additional pyrolysis projects were scrapped, along with steam crackers, including Sabic’s plant in the UK.

Market forces further complicate the picture. Europe’s plastic-recycling crisis affects both chemical and mechanical recycling, both of which are being undercut by an oversupply of cheap fossil-based plastic resins from the US and China. Nearly one million tonnes of recycling capacity has been lost over the past three years, and has been replaced by cheaper imports.

EU mandates are intended to reverse this downturn by reviving demand for recyclates. However, the absence of a clear “Made in Europe” clause means there is a risk that targets will be met through cheap imports that do not meet European standards.

Lobbying Brussels: bending the rules

Given that nearly 40% of plastic is used for packaging, the industry saw profitable opportunities ahead and seized them.

Over the last five years, all the major players have rushed to sell chemically recycled plastic to packaging manufacturers and sign offtake deals with pyrolysis oil suppliers across Europe, with a total disclosed capacity of around 600,000 tonnes per year. This allows them to claim that their products contain circular feedstock. Shell has led the way in this respect.

Simultaneously, they have intensified the lobbying at EU level that they started as early as 2019. Ultimately, they persuaded policymakers to bend the rules and subsidy schemes to fit their ambitions.

Following a public consultation launched in the summer of 2025, discussions around recycling-traceability requirements intensified. The European Commission yielded to pressure from Cefic and from PlasticsEurope: a revision of the 2023 implementing rules for plastic bottles was adopted, opening the door to the mass-balance approach and paving the way for its extension beyond bottles to the entire plastics regulatory framework.

Mass balance is also accepted in UK legislation and is the holy grail that makes chemical recycling attractive for packaging markets.

| Mass balance: an accounting method, not a physical guarantee |

| In chemical recycling, recycled plastic waste (such as pyrolysis oil) is mixed with large volumes of virgin fossil-based feedstock inside industrial plants. Once blended, the recycled and fossil materials cannot be physically separated. Under the mass-balance approach, companies are allowed to allocate the recycled content “on paper” to selected outputs – even if those products contain little or no recycled material in reality. Example: If 5 tonnes of recycled feedstock are mixed into a process producing 100 tonnes of plastic, a company may label 5 tonnes of output as “100% recycled”, even though those products may still contain up to 95% virgin fossil material. This system inflates recycled-content claims and associated carbon savings along the entire value chain, from petrochemical producers to consumer packaging — despite minimal physical recycling taking place. |

Kathy Heungens, Corporate Affairs Manager for Belgium at MARS and a member of the Consumers Good Forum, which supports the principles of both mass balance and avoided incineration principles for chemical recycling, told us: “We are [...] advancing towards compliance with the EU Regulation on recycled packaging (PPWR). The [...] collaboration with SABIC is one of the initiatives that fits in the vision above.”

Other brands that source packaging from SABIC did not respond to our request for comments.

The mass balance method is a contentious one among a number of environmental organisations: “Recycled content should be physically part of the final product through segregation or controlled-blending,” said Lauriane Veillard, Chemical Recycling and Plastic-to-Fuels Policy Officer at the NGO Zero Waste.

However, the industry argues that the two different feedstocks cannot be physically separated once they have been blended in the steam cracker.

“Building separate upgrading units just for pyrolysis oil is economically inefficient,” said Plastics Europe’s Röder. “Investment needs flexible co-processing rules aligned with commercial reality, scaling depends on favourable regulation.”

In fact, the EU is legally endorsing the voluntary system led by the industry-driven International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC). In recent years, ISCC mass-balance certificates have circulated among various stakeholders in the supply chain – from pyrolysis plants to plastic manufacturers and consumer brands – inflating figures at every stage.

ISCC is seeking government recognition. The EU leaves member states free to choose their own verification and reporting systems to ensure compliance with recycling targets .

“Based on paper certificates (i.e. from the ISCC), companies may claim as ‘sustainable’ packages that do not contain a single recycled molecule, which is false and misleading, and legally challengeable,” Maurer told us.

“Claims based on mass balance could conflict with the Empowering Consumers Directive (effective as of 2026) because product circularity and carbon savings cannot be guaranteed", commented Margaux Le Gallou from ECOS.

“The industry wants flexibility to label select packaging as ‘100% recycled’ and charge a circularity premium to end users, such as consumer brands and retailers,” said Lauriane Veillard of Net Zero Waste: "If mass balance is needed, it would be fairer to consumers to allocate recycled content proportionally to all outputs.”

“Allowing companies to allocate the ‘recycled’ label to the most profitable products distorts the market”,” said Jutta Paulus, Member of the European Parliament (MEP) from the Greens/European Free Alliance group. The group opposed the industry’s demands. “Small mechanical recyclers risk losing out as petrochemical multinationals dominate access to clean feedstock.” Maurer agrees: “Claims that chemical recycling handles complex waste are a myth, because in reality the process requires specific homogeneous plastics that are also ideal for mechanical recycling.”

The Commission’s half-opened door to new “recycled content”

The State of California labelled ISCC’s framework a fraud in a 2024 lawsuit against ExxonMobil, which has lobbied more than any other company for mass balance to be accepted in the EU.

The US multinational has paused its chemical recycling activities in Europe, awaiting clarification from the European Commission on how recycled volumes will be credited.

At the heart of the debate is the fact that only a portion of steam cracking output consists of monomers ready to be made into new plastic, with this figure only exceeding 50 % under optimal conditions. The rest consists of fuels and other industrial materials.

In order to prevent over-attribution, the Commission excluded fuels from the definition of “recycled”, in line with the Waste Framework Directive. However, it included other materials, leaving the door half-open.

“The non-fuel portion of the output consisting of materials different from polymers, such as lubricants, can be considered as recycled content and therefore count towards the EU targets, although it does not end up in plastic packaging”, noted Lauriane Veillard.

Assuming again a 100-tonne output consisting of 40% polymers (40 tonnes), 30% fuels (30 tonnes) and 30% other materials (30 tonnes), and a 5-tonne pyrolysis-oil input, the share counted as recycled content based on mass balance would be 5% of 70 tonnes instead of 40 tonnes, meaning 3.5 tonnes rather than 2 tonnes. At an industrial scale, this extra volume of 57% would be enormous, with exponentially increasing sales of packages bearing the “X% recycled” labels required by EU law..

“Now the industry wants a category of ‘dual use’ fuel accepted, which could count as recyclate if it is further refined into plastic (Ethylen and Propylen),” said Maurer.

We met Wolfgang Trunk, a senior official at the European Commission’s Environment Directorate in mid-November 2025 amid the tense standoff he was facing at a French Petroleum Institute conference, where he was surrounded by lobbyists from Cefic and the petrochemical champions BASF, BlueAlp, LyondellBasell and Dow: “[...] They say [...] 5% comes [...], from the plastic waste. And they want to have as much as possible that they can.[...] in this recycled content. And we have to avoid [...] that […] the 95%, which is purely fossil-based, [...] gets the label recycled”, he told us.

However, the leaked updated draft of the Commission's proposal validates the industry's request for a dual-use derogation. Nevertheless, producers must notify the quantity of fuel converted to plastic on a case-by-case basis.

“Rules are applied too rigidly; if allowed, a fuel use exempt approach could still support ‘100% recycled’ plastic claims”, said Roder. “How recycled content is allocated is a policy choice, not a scientific one.”

By allocating recycled content – including non-plastic fractions – to high-value packaging using a mathematical approach, pyrolysis-based plastic producers can boost revenues.

All of the top 14 petrochemical companies and a few consumer brands (HeinzKraft and Mondelez) that are tied to SABIC are ISCC-certified. The ISCC’s spokesperson told Voxeurop that “The Fuel-Use Excluded Approach is still under development, and no [...] user has yet been certified under this option”. This means that a considerable proportion of plastic advertised as recycled is actually fuel in disguise.

The ISCC will have to adapt its certification criteria to align with the upcoming EU regulations that require fuel to be excluded from recycled output.

However, the Commission's decision to implement the Single-Use Plastic Directive is still under discussion. The decision includes other materials in the definition of 'recycled content', leaving the door half open.

Public money, private gain

As well as exploiting legal loopholes, the industry has also secured taxpayers’ money.

“Until at least 2040, chemically recycled plastics will cost more than virgin materials; we need time and investment to reach industrial scale,” said Roder. “The industry is prepared to invest around €8 billion by 2030, but a supportive policy framework and short-term subsidies are essential.”

Our analysis shows that the EU budget, funded by national contributions, has channelled around €760 million into chemical recycling projects through grants and equity investments.

Our analysis shows that the EU budget, funded by national contributions, has channelled around €760 million into chemical recycling projects through grants and equity investments. It also shows that two-thirds of these subsidies go to pyrolysis, with almost half supporting pyrolysis-based plants that feed directly into the supply chains of the Top 14 petrochemical majors or their affiliates.

“Consumers are basically forced to subsidise the infrastructure that allows fossil fuel companies to illegitimately promote as ‘sustainable’ the plastic packaging consumers buy,” said Helmut Maurer.

Despite efforts by the Joint Research Centre (a special agency of the European Commission) to develop a standardised methodology, climate-performance requirements attached to the different EU funding schemes remain weak and blurred.

Horizon 2020 projects – with Spanish giant Repsol as the largest beneficiary – have no obligation to submit LCA studies demonstrating quantified emissions reductions as a precondition for funding.

Debt finance from the European Investment Bank and the InvestEU programme, backed by Chevron, requires projects to demonstrate a net reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, but does not specify whether the comparison should be with incineration or virgin plastic.

The same goes under Innovation Fund guidelines: companies are free to choose the most convenient business-as-usual baseline to demonstrate “avoided emissions”.

Most EU-funded companies, including Austria’s OMV group (owner of Borealis), compare emissions to waste incineration. Only a few, such as Italy’s ENI and Finland’s Neste, use virgin plastic as the baseline. Others compare with the combined emissions of both baselines.

Regardless of which reference scenario is used, the “avoided emissions” metric only considers emissions that are offset by replacing incinerated waste or virgin naphtha with an equivalent quantity of recycled feedstock. However, it does not take into account the total emissions produced by the process of making plastic from recycled materials, which SABIC’s own life cycle assessment (LCA) shows to be higher due to the high carbon intensity of pyrolysis.

NGOs argue that EU funding should only support recycling methods with a lower carbon footprint than virgin plastic at a process level, thus discouraging the use of avoided-emissions accounting.

For consumers, this creates a distorted picture. Most EU-funded companies’ websites, as well as those of the top 14 petrochemical companies and SABIC-linked consumer brands, fail to make it clear that their impressive carbon savings are merely offsets rather than actual reductions.

Furthermore, LCA methodologies, including those of EU-funded projects, remain confidential, thereby evading transparency and expert scrutiny. Companies and the Commission have refused to disclose information, even after the matter was escalated to the EU Ombudsman.

Europe laws set for a weak impact on plastic plague

Flawed accounting rules and weak subsidy conditions risk undermining the EU’s goal of increasing recycling and reducing plastic-related greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions in order to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050.

EU waste and packaging legislation merely states that recycled content should reduce carbon footprints in line with sustainability criteria that are yet to be defined by the Commission.

“Such criteria will ensure that […] recycled content […] reaps the maximum environmental benefits,” a Commission’s spokesperson told Voxeurop. Officials did not deny that pyrolysis-based plastic, which has higher emissions than virgin plastic, could count towards recycling targets. This would conflict with the EU taxonomy for responsible finance. Based on data from Morningstar, we found that asset managers have invested over €19 billion via EU-regulated “green” funds in the top 14 companies championing chemical recycling. Total Energies, Shell and Exxon Mobil represent almost 70% of these investments.

“Regulation and funding would better serve the environment if directed at improving product design to make plastics safer and easier to reuse,” commented Lee Bell of the International Pollutants Elimination Network.

According to calculations made by the Oeko-Institut, expanding mechanical recycling alongside increasing reusability could reduce GHG emissions by 45% compared with a greater reliance on chemical recycling.

“Much of the plastic targeted for chemical recycling should not exist in the first place,” concluder EU Commission’s advisor Helmut Maurer: “This is not about protecting the planet, but about protecting continuous plastic production and fossil carbon profits.”

🤝 This article is the result of a cross border investigation, supported by IJ4EU and coordinated by the independent journalist Ludovica Jona, with the media outlets The Guardian (UK), Voxeurop, Mediapart (France), Altreconomia (Italy), Público (Spain), Investigative Reporting Denmark, Deutsche Welle (Germany) and with reporters Lorenzo Sangermano and Lucy Taylor. Its production was supported by a grant from the Investigative Journalism for Europe (IJ4EU) fund. The International Press Institute (IPI), the European Journalism Centre (EJC) and any other partners in the IJ4EU fund are not responsible for the content published and any use made out of it.

O

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!