A 2016 study that surveyed gender-based violence across European Union member states revealed that 55 percent of Romanians, both men and women, consider non-consenual sexual contact justified in certain situations. For 30 percent of these respondents, rape was justified when the woman was in a group that had used drugs and alcohol, while for 25 percent, dressing “provocatively” could present a reasonable ground for sexual abuse.

Unsurprisingly, in 2021 the European Institute for Gender Equality ranked Romania in the third-last place on the European Gender Equality Index, just above Hungary and Greece . Mentalities according to which “a slap is not beating,” “if he beats me it means that he loves me,” or “a woman must be punched from time to time or she will grow too big for her boots'' (all these are popular sayings in Romania) are deeply entrenched into Romanian culture and unfortunately still hold ground. Insightful and at times difficult conversations with feminist activists, researchers, and NGOs revealed that gender-based violence is one of the most pressing issues Romanian women face at the moment.

Since 2000, which marked the first street protests against gender-based violence in Romania, the feminist movement achieved a lot: pushing the introduction of adequate legislation, offering support to victims, and raising awareness of the public. This movement has also made major strides in changing the way these stories by journalists and the mainstream media. This, however, is a broad field and its recent history alone could fill the pages of an entire book.

The Playboy protest

In April 2000, international media including the New York Times, CNN, and BBC, covered unprecedented protests in Bucharest led by women. It was in response to a bad joke on April Fools’ Day. Playboy Romania had published an article titled How to Beat Your Wife…Without Leaving Traces on Her Body, which described in detail ten proposed abuse methods, alongside a series of photos. The article suggested that a good beating might even lead to an elevated sexual experience, which a wife secretly craves. The article led to a fervent reaction from feminist activists who, for the first time in Romanian history, mobilised en masse against gender-based violence.

The protest in front of the Romanian Parliament included a letter-writing campaign to members of the Parliament and embassies. The event ended up on the front pages of international media and gained momentum as the first public impugnment against antiquated national policies regarding the condition of Romanian women. Christie Hafner, the then chairwoman of Playboy Enterprise, publicly apologised, reprimanded the magazine’s Romanian editor-in-chief, and made a small donation to Romanian NGOs working of gender-based violence.

In addition, the activists involved in the movement received an invitation to publish a series of articles in Playboy Romania. A temporary coalition of nine organisations dedicated to fighting gender-based violence was formed right in the aftermath of the protest, and the notions of “family violence” and “marital rape” were introduced in the Penal Code later that year. The main obstacle to the protest was, disappointingly, the lack of interest from national media, which stood in stark contrast to the international interest. Only the Romanian version of Cosmopolitan magazine covered the events of the protest.

“A crime of passion”

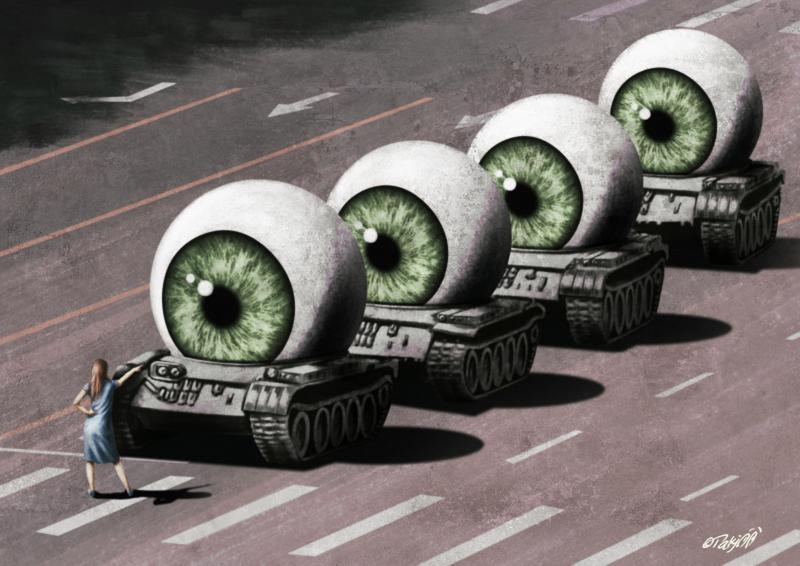

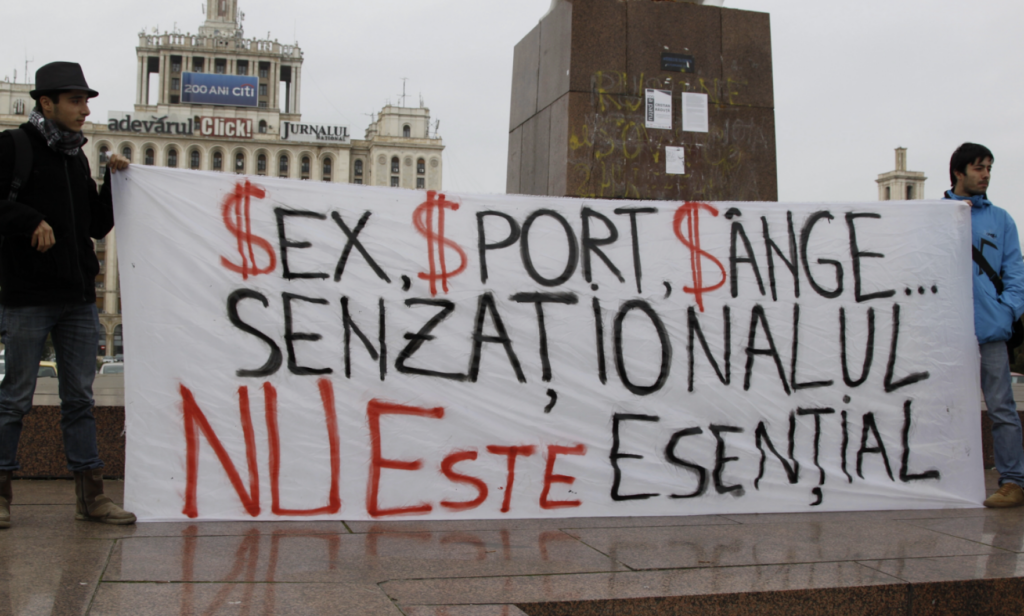

Gender-based violence is often exploited for entertainment in public spaces, on television, and in popular culture. Feminists noticed such cases in 2012, in the same year Romania recorded 14,000 cases of gender-based violence incidents – the number of reported cases.

As a result, three feminist groups organised a protest titled “Violența nu este divertisment!” (Violence is not Entertainment!), and used the space to stress the role of media in the sensationalisation of aggressive behaviour towards women, the mocking of victims, the hypersexualisation of women, and glossing over femicides through phrases such as “a crime of passion”, “murdered out of love” or “fatal attraction.” “The feminist activists demanded the adoption of an ethical code in journalism. Unfortunately, the event received almost no coverage in the media”, said Tudorina Mihai, president of the FRONT association (1).

In 2013, statistics showed that almost 30 percent of Romanians agreed that women are sometimes “responsible for being beaten” and 42 percent considered that domestic violence was not an issue of public interest. The same year, the Romanian government intended to “deal” with rape cases in a new mediation law that would have forced the accused and the victim into an informal dispute resolution, in an attempt to prevent such cases in front of the Court.

This law not only risked the empowerment of the aggressor, but also threatened to re-traumatise and discredit the victim. Feminist organisations were quick to organise street protests to oppose the law, and the demonstrations ultimately helped block the implementation of the law.

Women’s rights activism in Romania boomed at that period. Numerous organisations joined forces and formed, what would become, the most important network in the response to gender-based violence: VIF (The Romanian Network for Preventing and Combating Violence against Women).

Romania was the only EU country that offered no legal protection to victims of gender-based violence. FILIA Centre, one of the first Romanian feminist associations, launched the project “Femeile spun NU publicității ofensatoare” (Women Say no to Disrespectful Advertising!) in 2011, consisting of a catalogue of various disrespectful commercials, as well as a book on the same topic.

The same year, FILIA organised a demonstration in front of the Parliament to demand an improvement of the laws on the prevention and control of gender-based violence, as well as the adoption of a protection order law. On the protest “STOP violenţei asupra femeilor: Victimele nu mai pot aştepta!” (Stop Violence against Women: Victims can no Longer Wait!), feminist activists appeared with painted-on bruises, in bandages, and carried lighted candles in the memory of femicide victims. The activists stressed out that gender-based violence was not a private matter, and that it should be politicised.

Gender-based violence is often exploited for entertainment in public spaces, on television, and in popular culture

In 2012, the Perla Case became one of the most noted gender-based crimes covered in Romanian media to date. A husband shot and killed his wife in the hair salon in which she worked, called Perla. Prior to the murder, the victim Felicia Vădan, repeatedly reported her husband to the authorities in vain. As a consequence of this case, legal protection measures were put into place in Romania.

However, the law, police authorities, and the social systems were still far from able to provide the necessary protection in time. Victims needed to submit either a forensic examination report, witness declarations, or a record of previous complaint filed against the aggressor. A VIF research, carried out in 2013, showed that an average of 33 days were needed to obtain a protection order in Romania at that time.

Journalism for women’s safety

As a result of the 2012 protests against the media’s depiction of gender-based violence, journalism in Romania evolved. Numerous investigations contributed to raising awareness and the mobilisation of the political apparatus. In 2017, one investigation revealed that an overwhelming number of 500 proven and convicted paedophiles walked free due to suspensions of their sentences (According to the data, for each paedophile who was imprisoned, another three received a suspended sentence).

The same year, 400 of them were charged, not with rape, but with entertaining “sexual acts with minors”. Multiple judges considered that girls as young as ten were able to give their consent or that they were guilty of having aroused their subsequent aggressor with their dishabille (the state of being partly or carelessly dressed, Collins Dictionary. Ibid, 2019).

As a response to these disclosures, on 8 March 2019, the feminist group MulțumescPentruFlori (Thank You for the Flowers) organised the protest “Cum se scapă de-un viol, domnule judecător?” (How Does One Get Away With a Rape, Mr. Judge?) in front of the National Court of Law. The feminists asked authorities to stop the judgment of cases based on a victim’s outfit or level of alcohol consumption, to stop the investigation of abusers in a state of freedom, to continue to monitor abusers even after they served their sentence, and to simplify institutional procedures in order to avoid the re-traumatisation of victims.

In 2019, judicial and police courts – who more often than not treated victims’ complaints with indifference, ignorance, or even mockery – began to be held accountable. The Caracal Case — where two teenage girls were kidnapped, raped, and murdered by a 65-year-old man – shocked the public. One of the girls, 15, kidnapped, wire-tied, and raped, managed to call the police describing her location and ask for help. The dispatcher’s answer subsequently became viral: “Ok, ok stay there. Remain there. I am calling a crew but stop keeping the line busy.” Only one hour later did the same dispatcher ask a special telecommunications service how to localise a call. By the time the police were able to get a search warrant and finally intervene, it was too late. The perpetrator was sentenced three years later, in September 2022.

The Romanian independent theatre got involved in the feminist cause. Two theatre artists, playwright Alexandra Felseghi and director Adina Lazăr, created a play inspired from the Caracal Case, titled Nu mai ține linia ocupată ("Stop Keeping the Line Busy"). A few months later, in solidarity with the two victims, feminists groups organised a nation-wide protest in major Romanian cities, as well as in front of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, titled “Cade una, cădem toate!” (If One Falls, We all Fall!). When the event was over, the phrases “Sexism Kills” and “Racism Kills” were written on the building of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which led to conflicts between protesters and guards.

Civil society’s alliance with journalism

Until 2021, sex abuses against minors could still be considered legal and consensual sex acts, even if the victims were children at the age of nine. Civil society activists, however, had had enough of suspended sentences for rape (2). Thus, under the banner Media X Files (3), a group of journalists wrote 20 articles in the span of one year, documenting cases of gender-based violence. Their efforts forced the authorities to issue a Judiciary Report, as the result of an investigation on the judiciary practices in cases of sexual misconduct involving underage victims.

Some of the statements from the sentencing rulings were “the victim consented”, “the underage girl does it with her mother’s approval”, the 11-year-old girl consented “because she was not a virgin at the moment of incriminated sexual act”, “she already had a relationship with the defender, proof being they already had two children together”.

The past 20 years of Romanian feminism show that unrelenting feminist activism can bring positive changes at social, legal, and policy levels

Such arguments used in a legal setting revealed a rape culture that blamed the victim, even in cases where the victim was child. Besides the absence of a law that clearly defined all sexual acts with minors as a felony, the next issue the report uncovered was related to depositions. The Judiciary Report revealed that there were no special rooms or safe spaces for victims. Instead, the depositions took place in the same room with the aggressor. Moreover, the involved authorities lacked special training and their handling of the cases often led to victims being re-traumatised.

Gender-based violence within the Roma community is not addressed by governmental policies, and preconceptions about the Roma culture often determine the absence of juridical action. The E-Romnja, a feminist, non-profit Roma organisation, has been fighting for the rights of Roma women through advocacy campaigns and community development since 2012. One of their studies, Phenja: Suroritatea dintre femei împotriva violenței de gen (Phenja: the women sisterhood against gender violence) by Ioana Vrăbiescu, carried out among Roma and non-Roma women in the town of Giurgiu, revealed how women perceive gender-based violence.

In conversations with victims of violence from their romantic partners, all participants emphasised that they are “less affected by physical abuse than by verbal abuse,” which they do not define as domestic violence. Most of the women differentiated between abuse from biological kin and abuse suffered from spouses: “It is one thing to be hit by a parent, and another by a husband.”

Counterintuitively, their attitude towards victims of domestic violence was that of victim blaming, including cases where the interviewees themselves were the victim. In addition, marital rape was not perceived as a form of (sexual) violence. Sexual harassment within the family, in the neighbourhood, or within the social circle was regulated through communitarian rules, not the law.

There were no cases of rape filed to the police in Giurgiu, ever, and a sexual act in this particular community was considered rape only if there were more than one men involved in it and if the victim displayed visible traces of violence. None of the 24 women victims of gender-based violence interviewed ever reported their cases to the police.

The Valea Seaca (Dry Valley) commune in Eastern Romania, located 90 kilometres from the nearest city, is made-up of a 50 percent Roma population. Since 2015, the feminist initiatives of E-Romnja here included weekly meetings aimed at informing on and eradicating gender-based violence, empowering women and encouraging civic participation, education on sexual and reproductive rights, and education of children about bullying.

In our conversation, Anca Nica – one of the e-Romnja representatives – mentioned that at the beginning of their work in Valea Seaca, there were no cases of men prosecuted for gender-based violence. In 2020, as the result of a sexual abuse case involving an 8-year-old victim, where the perpetrator was her grandfather, the women of Valea Seaca organised a protest in front of the police station to raise the awareness of police passivity in cases of abuse and violence against Roma girls and women.

According to Nica, following the protest, the public defendant filed a demand for the revision of the procedures of intervention in cases of sexual abuse in the area, and the official inquiry revealed that, in fact, the police had no protocol for these cases. Things changed drastically once the feminist actions began. Women learned more about their reproductive health, realised that there is no justification for gender-based violence, and participated in the “Împreună pentru siguranța femeilor” (Together For Women Safety) march.

Thanks to the initiatives of E-Romnja, women not only in Valea Seaca, but in other parts of Romania, had the chance to participate in educational activities on gender-based violence, underage and/or forced marriage, fighting school drop-out rates, and obtaining of identity papers for unattested citizens.

The perception of feminism in Romania

The past 20 years of Romanian feminism show that unrelenting feminist activism can bring positive changes at social, legal, and policy levels. Success stories revealed that it is essential to educate and empower women to voice their concerns around gender-based violence, and to demand the change they want to see in their lives.

Their feminist fight, however, continues and it will not stop until authorities take over the responsibilities in the protection of victims and prosecution of perpetrators, the public discourse around gender-based violence and feminism in general is changed, and gender-based violence is eradicated.

Nevertheless, the struggle for an equitable society, in which women are treated equally, regardless of their ethnicity is, and will continue to be, one of the toughest. Protection and education of girls and women, especially those from vulnerable and marginalised communities, such as the Roma community, is a work in progress that has started only recently but has seen crucial improvement. On this path, numerous feminist associations and groups have taken over this responsibility, which in fact, should be the responsibility of the state. We have, indeed, a long way ahead, but the progress is visible day by day.

🤝 Published in collaboration with the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung. 👉 This article was originally published in Stories of Feminist Mobilisation: How to Advance Feminist Movement Worldwide in English and in Romanian on Scena9

Notes

1) FRONT is made up of feminists who militate for equality between women and men, as well as for elimination of other types of discrimination through public demonstrations, lobbying and advocacy, education and research, sex education in schools, etc.

2) CEDO had already found the Romanian State guilty in 2016. In a case implying two victims, Romanian judges decided to sentence the aggressors for sexual acts with a minor, rather than for rape.

3) Media X Files was an initiative aimed to investigate and publish 16 pieces about the topic of gender-based violence in 2020.

References

Interviews

Sincere acknowledgment to Laura Grunberg, Daniela Drăghici, Anca Nică, and Tudorina Mihai, who contributed with their time and knowledge to the writing of this article.

Other Sources

ANES. (2018). Raportul final privind implementarea Strategiei naţionale pentru prevenirea şi combaterea fenomenului violenţei în familie pentru perioada 2013-2017 [The Final Report on the National Strategy for preventing and fighting the family violence between 2013-2017]

Asociatia Transcena. (2013). Studiu la nivel naţional cu privire la implementarea ordinului de protecţie [National Study on the Implementation of the Protection Order].

Bragă A., Neaga, D., & Nica Georgiana A. (2017). Toată lumea știa [Everybody knew]. Bucharest: Hecate.

Ciobanu, A. M., & Sandu, O. (2016). Inegalitatea de Acasă [The Inequality from Home]. DOR.

Digi24. (2019). Discuția halucinantă între polițist și Alexandra: „Bine, bine, stai acolo! Nu mai ține linia ocupată” [The Unbelievable Conversation Between the Policeman and Alexandra: “Okay, okay, stay there! Stop keeping the line busy”]

European Institute for Gender Equality. (2021). Gender Equality Index 2021.

European Commission. (2016). Gender-based Violence Eurobarometer.

E-Romnja. (2021). Grassroot work - A model of civic engagement for Roma Women.

Hotnews. (2022). Cazul Caracal: Gheorghe Dincă, condamnat la 30 de ani de închisoare în primă instanță [Caracal case: Gheorghe Dincă Sentenced to 30 Years in Prison at First Instance].

Iancu, A. (2013). De ce legea medierii nedreptăţeşte victimele violurilor [Why Mediation Law Does Injustice to Rape Victims]. Feminism Romania.

INOSCOP Research. (2013). Barometrul de opinie publică – Adevărul despre România [Public Opinion Barometer - The Truth about Romania].

Lincan, G. (2020). De ce avem nevoie de feminism rom [Why Do We Need Roma Feminism], Inclusiv.

Mihai,T. (2018). Apel către deputați pentru susținerea proiectului de lege pentru siguranța femeilor! [Call on MEPs to support the Women's Safety Bill!]. www.violentaimpotrivafemeilor.ro/.

Miroiu, M. (2015). Mişcări feministe şi ecologiste în România (1990-2014) [Feminist and ecologist movements in Romania 1990-2014]. Iași: POLIOROM. http://elibrary.snspa.ro/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Miscari-feministe.pdf

Oncioiu D., & and Stoicescu, V. (2021). JUSTIȚIE DISECATĂ. Avem raportul Inspecției Judiciare care documentează cum tratează statul român infracțiunile sexuale cu victime copii [JUSTICE SCRUTINIZED. Here the Judicial Inspectorate Report Documenting How the Romanian State Treats Sex Crimes with Child Victims].

Dela0. Stoica, O. (2022). Nu mai ține linia ocupată [Stop Keeping the Line Busy]. Scena9.

Tolontan et. al. (2019). Cum batjocorește justiția fetele de 10 ani violate. Procuror și judecător: ‘Victima s-a îmbrăcat sumar și a consimțit actele sexuale’! [How justice mocks raped 10-year-old girls. Prosecutor and judge: ‘Victim Dressed Scantily and Consented to Sexual Acts’!]. Libertatea.

Tolontan et. al. (2018). Ministerul Justiției recunoaște: peste 500 de pedofili dovediți și condamnați sunt în libertate, în loc de închisoare! [Ministry of Justice Admits: Over 500 Proven and Convicted Paedophiles Are at Large Instead of in Prison!]. Tolo.ro.

Vrăbiescu, I. (2021). Phenja: Suroritatea dintre femei împotriva violenței de gen [Phenja: the women sisterhood against gender violence]. E-Romnja.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!