In early July, a week after taking office as minister of migration and asylum in Greece, islamophobic and antisemitic far-right leader Thanos Plevris posted brief remarks on X in response to a comment by a lawyer. The jurist, pointing to an article he had himself written on the subject, had admonished the minister that “if the [1951] Geneva Convention on Refugees is not revised [...], nothing will change!” Mr Plevris assured him that he had read the article and agreed that, “indeed, the Geneva Convention addressed issues from the 1950s and cannot address the issue in 2025 of massive [migration] flows”.

A few days later, during a debate in parliament on an amendment suspending the registration of asylum applications, Plevris demonstrated his idiosyncratic understanding of the 1951 Refugee Convention and the matters it was intended to regulate. “The Geneva [Refugee] Convention was created to protect people who were fleeing the Soviet Union”, he declared, to loud applause from the MPs from the ruling New Democracy party (center-right). His comment was addressed to the Communist MPs, whose invocations of the convention he considered misguided. Mr Plevris did not reveal sources to back up his assertion. However, almost all scholars of the document disagree with him.

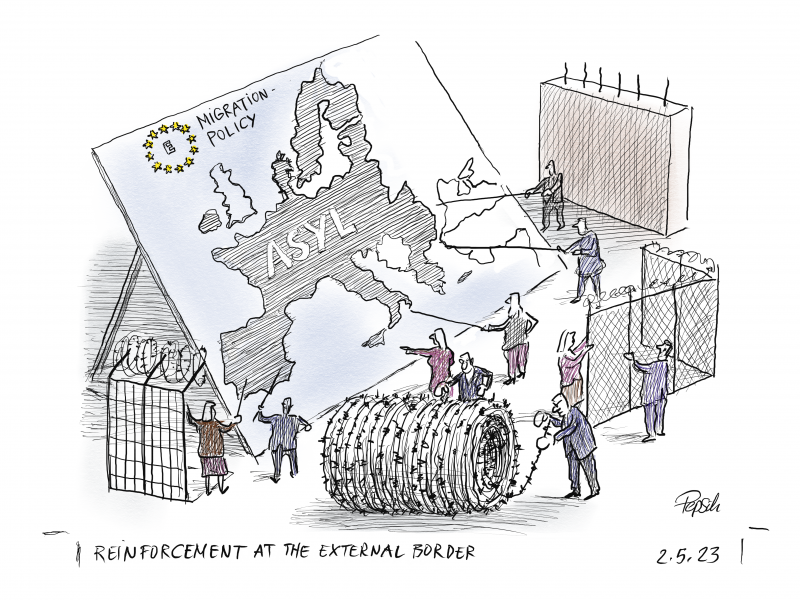

What is certain is that Thanos Plevris's declaration is yet another concession by Greece’s government to the far right. What were previously marginal positions are increasingly becoming official policy and the subject of polite debate throughout Europe.

To date, the government's repeated refrain in relation to human rights has been that it always acts within the framework of international law. It has argued this in response to criticism of its capricious laws to get around the Refugee Convention (notably including three-month suspensions of asylum applications in March 2020 and last July) and its systematic violations of the text in practice via its informal refoulements (pushbacks of migrants).

The government's declarations of respect for international law may be hypocritical, but its actions also demonstrate a distinct political philosophy which is gaining ground in Europe. In that vision, the rule of law is being gradually replaced by a regime in which people are arbitrarily deprived of their rights, discriminated against and made to live in intolerable conditions and with no means of protest.

| What is the Refugee Convention? |

| The Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees establishes the post-war asylum system and defines the obligations of states to protect refugees. Its basic principle is non-refoulement, which prohibits the expulsion of refugees to a country where their life or freedom is threatened. The convention was signed in Geneva in July 1951 by 24 countries and has since been ratified by 145 UN member states. In its original form, it provided protection for refugees who had left European countries before 1951. Later, with a 1967 protocol, the convention was extended to cover refugees from across the world without any time limit. The UN High Commissioner for Refugees is the guardian of the convention in cooperation with UN member states. |

Italy Meloni’s very own interpretation

Those who question international human-rights law may do so openly, but they usually use careful language in their statements for foreign consumption. One example of this is the absurd line that “there was no mass irregular migration and human trafficking” at the time the Refugee Convention was drafted, as Italian prime minister Giorgia Meloni asserted at this year's UN General Assembly.

On the sidelines of that event, the Trump administration hosted a conference entitled “The Global Refugee and Asylum System: What Went Wrong and How to Fix It”. Washington proposed nothing less than the abolition of the principle of non-refoulement, a mainstay of the 1951 convention which bans refugees from being returned to countries where their lives or freedom are threatened – the so-called pushbacks. In practice, the Trump administration itself is blatantly violating the principle of non-refoulement and the rule of law, and building its own regime of arbitrariness and terror. Meloni has shown the same contempt for the rule of law, criticizing Italy’s judges for putting the brakes on her xenophobic policies. A case in point was Rome's notorious plan, which morphed into a fiasco, for detention centres in Albania.

International conventions, “when interpreted ideologically by judges with a political agenda, end up trampling on legality instead of upholding it”, Meloni said. She added that “the UN cannot turn a blind eye and protect criminals in the name of rights”.

This was preceded in May by an open letter from the leaders of nine European countries. An initiative of Italy and Denmark (and co-signed by Austria, Belgium, Estonia, Czechia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, and the United Kingdom), the letter asked the European Court of Human Rights to change its approach to irregular immigration and the deportation of foreigners who commit crimes, and generally to apply the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) more flexibly.

The UK’s long walk out of the ECHR

In Britain, the campaign to challenge the ECHR began fifteen years ago. In 2011, Prime Minister David Cameron remarked that he was sick at the idea that convicted criminals might gain voting rights, referring to an earlier ruling by the Strasbourg court that vindicated a convicted murderer who had appealed against British legislation on the deprivation of voting rights. That same year, Home Secretary Theresa May criticized a court ruling that overturned the deportation of a Bolivian immigrant, falsely claiming that the decision was based on the immigrant's right not to be separated from his cat.

At the Conservative Party conference in early October, party leader Kemi Badenoch, under pressure from a right-wing insurgency by Reform UK under Brexit champion Nigel Farage, pledged to include Britain’s withdrawal from the ECHR in the Conservative election manifesto.

Critics of the ECHR are unhappy because the courts have allowed irregular migrants to remain in the country on the basis of Article 8 (on the protection of family life) and prevented deportations when they consider that there is a risk of inhuman and degrading treatment and torture (prohibited by Article 3).

On the side of the Labour government, Prime Minister Keir Starmer, who had a long career as a human-rights lawyer, has embarked on a delicate tightrope walk. He remains strongly supportive of the UK's continued membership of the European Convention, all while announcing laws that will impose the government's own interpretation of the document’s controversial clauses.

He has overtly criticized a court ruling that allowed, on the basis of Article 8, a Palestinian family of six from Gaza to join a brother living in Britain. The prime minister hinted at further such moves, noting that deportation decisions have been overturned on the basis of provisions not just in the Refugee Convention, but also the Convention against Torture and the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

Marine Le Pen hands the anti-ECHR baton over to the right

In France, Marine Le Pen once declared, in her 2019 New Year's message, that she favoured a French withdrawal from “the straitjacket of the European Convention”. She walked back this position ten months before the May 2022 presidential election. The attack on the ECHR was subsequently led by Eric Zemmour, the other far-right candidate in that election, and the conservative Les Républicains, who proposed amending the French constitution to allow derogations from international conventions in the case of immigrants.

Austria’s long-lasting criticism

In Austria, the far-right FPÖ and the conservative ÖVP have been challenging international conventions for more than a decade. Sebastian Kurz began criticizing international law on becoming foreign minister in 2013. In 2016, a year before being elected chancellor, he asserted that certain provisions of the Refugee Convention were outdated.

Last July, the ÖVP government's minister for European and constitutional affairs, Caroline Edtstadler, came out in favour of revising the convention on the grounds that “it comes from a pre-globalised era, in which the cross-border movements of migrants that we see today were not foreseen”.

Vox’ mass deportation from Spain plan

When it comes to xenophobia, the far right has proven that it has a fertile imagination. Spain's nationalist Vox party is now proposing to deport legal migrants and even Spanish citizens who “have not integrated into society and culture”, and to make “acceptance of Spanish culture and way of life” a prerequisite for remaining in the country. Rothio de Mer, a Vox councillor in Almería, has committed the party to the unworkably complex policy of repatriating 8 million refugees and immigrants who have recently arrived in Spain and are struggling to adapt to Spanish customs and traditions.

Iliana Savova, director of legal protection for refugees and migrants at the Bulgarian Helsinki Committee, sees talk of stricter immigration policies as propaganda by far-right and conservative parties that aim to stoke fear in order to manipulate and mobilise voters. She adds that to demand revisions to human-rights conventions is a dangerously slippery slope. “If such a debate is taking place in Europe today, it means that Europe is returning to fascism, which I hope will not happen.”

Greece’s own revisionists

The few articles published in the Greek press in support of revising the Refugee Convention make it clear what political agenda they serve. In a piece entitled “The Geneva Convention on Refugees – a back door to illegal immigration”, posted on 16 June 2020 on the website of the Union of Greek Lawyers, Ioannis Gkitsakis, a jurist at Greece's supreme court, describes the 1951 convention as outdated.

He cites a number of reasons, including that it does not allow for the suspension of its application; that it does not prevent the submission of asylum applications by those who are not entitled to international protection; that it provides for individual examination of each application and forbids grouped rejections of applications “submitted by several persons from the same country of origin, which is considered a safe country”; and that it outlaws “collective measures, such as mass expulsions or refoulements [...] against persons who share common characteristics, such as a common country of origin or a common mode of illegal entry”.

A post by Ioannis Gitsakis on X dispels any doubts about his motives: “Anyone who enters the country illegally has no right to apply for asylum. They must be held in a closed detention centre (or on a deserted island, a decommissioned ship, or a rented facility in Africa), without receiving benefits, until they are deported or leave voluntarily!” In other posts, he refers to “illegal Muslim immigrants”, the woke and LGBTQI agenda; the need to reinstate the death penalty; Israel’s leader Benjamin Netanyahu, who “took it upon himself to clean up the entire planet”; and EAM, Greece's wartime anti-Nazi resistance movement, which “was simply a murderous failed communist organisation”.

In an article published on Capital.gr on 24 September 2024 entitled “Will we let 'Geneva' destroy Europe?”, the author Thanos Tzimeros seconds Ioannis Gitsakis’s article. After referring, among other things, to “cannibalistic tribes” in Africa and “invaders” with a “primitive tradition of violence [...] written in their genes”, Tzimeros concludes that states have the right to close borders via refoulements, as well as to make “arrests, imprisonments, and deportations”, and to use live gunfire. “[The state] decides for itself. Not well-fed UN bureaucrats. Nor the 1951 Geneva Convention. The Convention must be revised yesterday.”

The head of Greece’s Asylum Service, Marios Kaleas, came out in favour of revising the 1951 convention in an article in Vima on 22 October entitled “Reassessing the Geneva Convention in a new era of migration”. Without resorting to extreme language, Mr Kaleas criticizes the document for, among other things, not providing for mechanisms to return those who are not entitled to international protection, and for its “rigid legal scope [which] has created room for divergent national interpretations and procedural inconsistencies”.

👉 Original article on Efsyn

🤝 This article was produced as part of the European PULSE project, in which Ef.Syn participates. Adrian Burtin (Voxeurop – France), Nikola Lalov (Mediapool – Bulgaria), and Ana Somavilla (El Confidencial – Spain) contributed to it.

📄 Have your say in European journalism! Join readers from across Europe who are helping us shape more connected, cross-border reporting on European affairs.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!