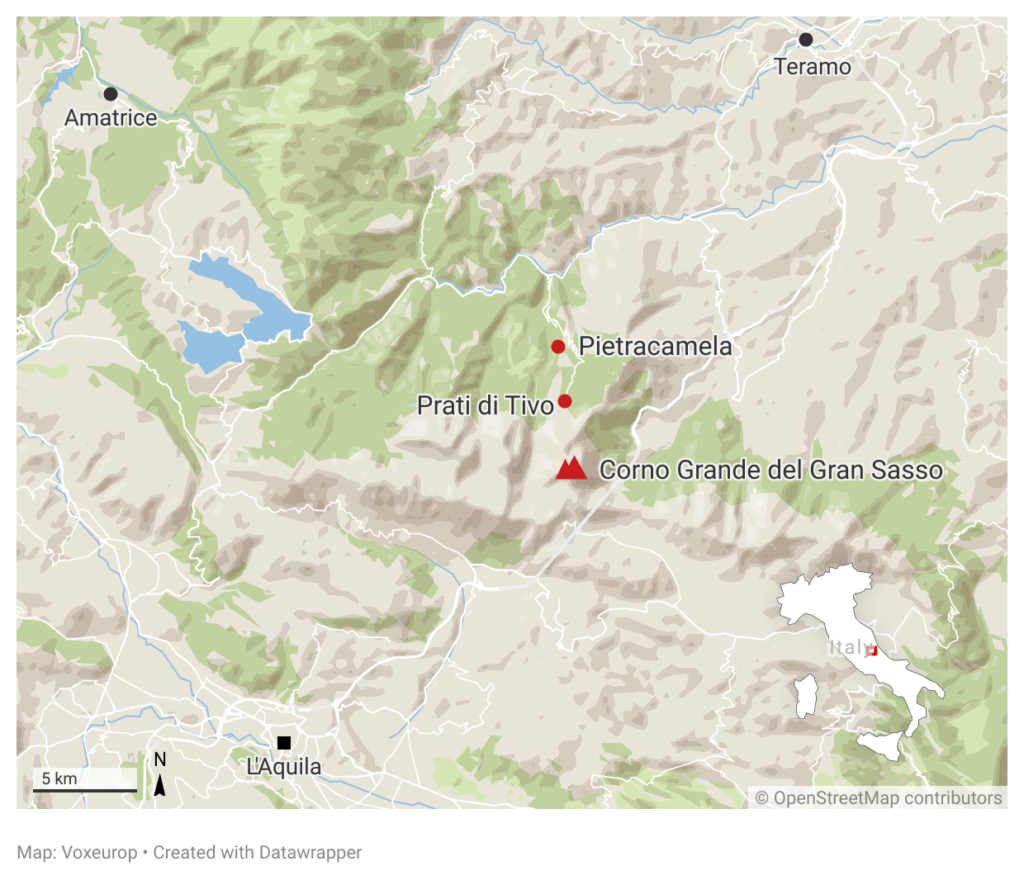

Pietracamela. At the end of the winter season, Pietracamela, in central-southern Italy, looks like a ghost village. A lone dog barks, curtains twitch behind wood-framed windows. Between the two highest peaks of the Apennines, the glacier creaks as its ice melts. In spring, avalanches are frequent. A thousand metres downstream, small rivers swell. Pietracarmela’s residents are confronting the effects of climate change.

Europe's mountains are warming at almost twice the rate of the rest of the continent. This gives us a glimpse of the future: increasingly extreme weather events, and increasingly extreme consequences. In the mountains, snowfalls are either rarer or more intense, weather conditions change unexpectedly, and glaciers inevitably retreat. Local communities are retreating with them.

Gran Sasso, Italy's highest mountain, offers an illustration of this. Pietracamela, the nearest village to Gran Sasso, was once a fashionable tourist destination with three clubs and a piano bar. That is now a memory. The petrol station still displays prices in lira, while the four luxury hotels are now closed during the winter.

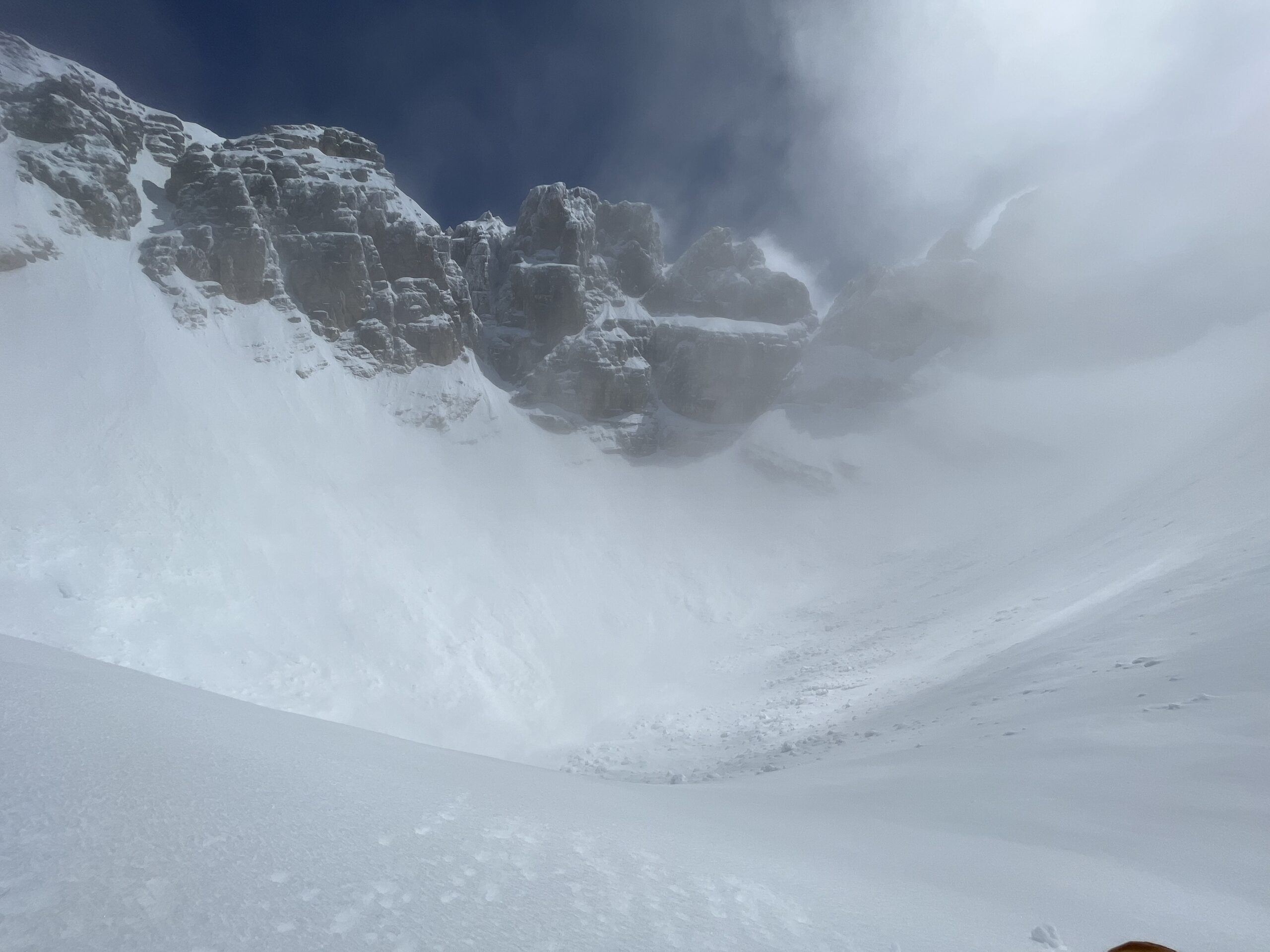

Calderone, Gran Sasso's glacier – one of the southernmost in Europe – is losing its status. Or rather, it has already lost it.

Between 1999 and 2000 it split into two smaller pieces, two "glacierets" or "snowfields" in scientific terminology. This process, which downgraded Calderone to a "glacial system", coincided with the shortening of the ski season.

Older residents remember that it was possible to ski on the slopes of Prati di Tivo from November to May, and even longer on the glacier. Now the first snow often falls after New Year's Day. "In the last five to ten years, snowfall has been rare in winter, but very frequent in April and May," confirms Massimo Pecci, an expert on the Calderone at the Italian Glaciological Committee. Pecci, who is also a professor of glaciology and an avalanche specialist, explains that the situation is similar in many of Italy's nearly four thousand mountain communities.

Ski lifts currently do not work and artificial snow systems remain idle even when potentially useful in early winter. In winter and spring, the only tourists who come are those interested in ski mountaineering. This sport requires strenuous ascents and makes less use of local businesses.

Dangerous snow

First possible conclusion: changing precipitation is the main factor affecting winter tourism. In a way, this interpretation is correct: Pasquale Iannetti, my guide on the glacier, says that the walk from Prati di Tivo to Calderone usually takes three hours, but on 1 May it took almost ten because "the snow conditions during the ascent were unprecedented, the snow was extremely muddy". In other words, dangerous.

However, to emphasise the difficulties of winter tourism is to oversimplify. The reality is more like a complex vicious circle: winter activities are more difficult and costly to plan for; so mountain villages have less stable income; so they attract fewer residents; and so support for new public investment, including infrastructure, declines.

This, in turn, will slow down any revitalization. For example, the owners of old stone houses, which are less resistant to earthquakes, fear to return. They are thinking of the earthquakes that have struck the area twice in seven years in the last 15 years. Others cannot stay overnight in their houses because they are still being renovated.

Seismic zones

The area between Abruzzo and Lazio was badly damaged by the 2009 and 2016-17 quakes. Reconstruction is taking longer than in more populated or better known towns, such as the epicentres of L'Aquila and Amatrice, where the death toll was higher.

The delays in Pietracamela are partly due to its geographical location and the lack of local shops. Poor infrastructure, including roads, is an obstacle. Construction workers have to travel by van every morning, often in extreme weather conditions. The nearest supermarket is about 20 minutes away by car.

Some of the existing infrastructure and buildings may fall into disrepair, and with them the village may lose its identity. "Houses that were used as holiday homes are still closed. The owners have lost the habit of coming back," comments Salvatore Florimbi, Pietracamela's municipal councillor.

Given these developments, it is not surprising that the state-owned operator of the local ski facilities has gone bankrupt. For more than four years, people have been trying to find a solution to what residents call a case of mismanagement of public infrastructure. The functioning of the cable cars is crucial to the recovery of tourism in the area, many locals say.

As the pie shrinks and business activity declines, divisions are emerging among those locals. Indeed, tensions are hampering cooperation, to the point that after the 2020 local elections the new administration spoke of 'liberation'. This word has a charged meaning in Italian, referring to the fall of the fascist regime.

It could be argued that this is just a matter of tourism and socio-economic difficulties. But that is not quite the case. The financial flow associated with tourism is essential for basic services. This includes snow removal, and in particular controlled avalanches, which are artificially triggered to prevent the accumulation of snow, a potentially dangerous phenomenon.

"Mountains need constant attention. Without maintenance and monitoring, avalanches are more likely. It's nature taking over," adds Pecci. Indeed, that is exactly what is happening. The number of wolves in Pietracamela is on the rise, since Abruzzo is an ideal habitat for them. Deer and wild boars can often be seen crossing the village streets, especially at sunset.

Wild animals are replacing people. There are no more schools in the area. The region's "young Sherpas" are now in their 40s and 50s. Intermesoli, a hamlet in Pietracamela, recently welcomed its first two children after almost two decades without a birth.

"If things continue like this, Pietracamela will disappear. In 20 to 25 years there will be no one left here," predicts Linda Montauti, owner of one of the two restaurants. According to official figures, the population fell from 1,392 at the end of the 19th century to 310 in 2002. Twenty years later, the number of inhabitants had fallen to 222. For the locals, however, these figures are "theoretical".

€2,500 to settle in Pietracamela

Among other incentives, the Abruzzo government offers €2,500 for each new household that moves to a mountain village with fewer than 3000 inhabitants. The region offers €5,000 if the household starts a new business that will remain open for at least three years. This incentive does not automatically result in permanent and stable residence. According to locals, the actual number of permanent residents is around 25 to 30 people.

Linda's father, a former mayor of Pietracamela, adds that politics is also an obstacle. As the population dwindles, national policy pays less attention to the needs of sparsely populated areas. "We have only a few votes. The coastal towns are given priority because they may carry the day in regional and national elections," stresses Luigi Montauti. During his three terms as mayor he has tried to get a new road built, without success. At the moment there is only one way to get to Prati di Tivo, a ski resort a few kilometres from the town hall. It is the same road that leads to Pietracamela and Intermesoli.

Despite the tensions, the three municipalities are not giving up. They are concentrating on summer mountain sports. Over the past 15 years, Iannetti and other local guides have opened new climbing routes, while the authorities are trying to include the village in a new network of hiking trails. Pietracamela is also considering how to use the temporary houses for earthquake victims that are gradually being vacated. Perhaps it could offer them as residencies for artists, including international ones.

With a declining population and high alcohol consumption among men, young people are a valuable resource for Prati di Tivo, Intermesoli and Pietracamela. As is visibility: Pietracamela is on the list of the most beautiful villages in Italy. For the time being, it is the women who run most of the local businesses. Their children often live elsewhere – some in Pescara, others in Milan.

The town council is currently working on a cable car to link Pietracamela with nearby Fano Adriano. "We want to spread the tourist flow over several months. Summer tourism is buoyant, but not enough to make all the existing amenities work," explains Florimbi.

On a clear day, from Corno Grande (2912 metres) at the top of Gran Sasso massif, one can see both Italian coasts, the Adriatic and the Tyrrhenian. Given its proximity to Rome, it seems logical that this destination could attract young tourists, and perhaps even some new residents.

But teenagers in Teramo, the provincial capital, are not enthusiastic. "There is no interest at the moment. My students see the mountains as a challenging experience. I bring them here, but they don't appreciate it. They prefer the sea," says Rosaria Fidanza, a teacher at a hotel school in Teramo, a 40-minute drive away.

The sea, also in the province of Teramo, is 20 minutes from her home. Abruzzo's seaside resorts have seen their population grow over the past decade, and have welcomed victims of the series of earthquakes that hit central Italy in 2016-2017.

By contrast, Pietracamela, an hour's drive from the coast, is not far from the epicentre of several earthquakes. It is in the centre of the Gran Sasso and Monti della Laga National Park, which imposes strict rules on nature conservation. In the case of the cable car, the question is whether the infrastructure and its construction might damage the nesting sites of peregrine falcons and golden eagles.

Biodiversity, at least, seems unthreatened. The local gendarmerie even reports that a bear has returned to these mountains. At least for the time being, the region is fortunate not to suffer from the same water problems as other mountain areas.

"In the last two years, the problem of drought in the mountains of central Italy [the Apennines] has been less serious. On the other hand, in northern Italy, in the Alps, the two years of drought that have just passed are a harbinger of what could become one of the major problems of the coming years and decades: the aridity of Europe's mountains," explains Vanda Bonardo, an expert with the environmental association Legambiente.

Pietracamela's situation is complicated but also strikingly normal. Climate change will cause snow and glaciers to melt. That much is certain. What is uncertain is the ability of local communities to adapt to all the extremes and disruptions that climate change will bring.

Experts agree, however, that there is no shortage of opportunities. "Heat waves will become even more common in cities, so there could be a migration to cooler areas during the summer months," says Bonardo. Indeed, Pietracamela saw an increase in overnight stays during the pandemic.

The history of the Calderone has been one of constant change and that will surely not change. Agriculture faded away decades ago, and now winter tourism is set to become less relevant. To survive, locals will need to find a new identity and a new business model.

The municipality of Pietracamela is then a perfect example of how a fast-changing climate will require a handover between generations. After all, there is no sustainability without continuity.

Supported by Journalismfund Europe

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!