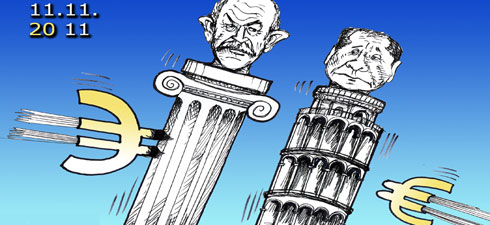

At the height of the economic crisis in the wake of a multitude of poor political decisions, not least those taken by outgoing prime ministers, non-politicians are increasingly taking centre stage.

Here, in Greece, we have central banker Lucas Papademos. In Italy, which is tipped to be the eurozone’s next weak link in the debt crisis, the government has disappeared and a former member of the European Commission with close links to the European banking system will lead the administration that is set to replace it.

The similarities are remarkable. In both cases, the political system has proved to be unable to take charge of the crisis. In Greece, socialist George Papandreou’s government, despite its complete compliance with the demands of European creditors, lost the confidence of the people, especially after the outgoing prime minister’s decision and subsequent about-turn on the organisation of a referendum — a wobble which marked the beginning of the end and largely facilitated the formation of a coalition with the right.

Berlin, Paris and Brussels took advantage of the opportunity to demand that the two main parties cooperate under the leadership of a technocrat, because they had no futher confidence in the country’s politicians. Mr Papandreou was effectively sidelined in the wake of his proposal for a referendum.

A new reality

Faced with a choice between pursuing his personal ambitions and satisfying the demands of his supporters, his rival New Democracy leader Antonis Samaras, backed down on his conditions and pledged to give full backing to Papademos and the decisions that his government will implement in the course of his mandate, which both parties have agreed will last until next February.

But a new reality has now emerged. The Papademos government will have to finalise the 2012 budget and ensure the ratification of the 27 October European agreement, which provides for a 50% reduction in outstanding debt and the implementation of further austerity measures.

It is not certain that he will succeed in achieving these objectives before the end of his mandate. He has the support of the Europeans, who, on paper, have greater confidence in his ability to apply the 27 October agreement. And they would not be opposed to an extension of his government’s mandate.

Of course, all of this will depend on the internal situation, the appetites and needs of political parties, leaders and MPs. But many things have changed, and his success in this venture cannot be ruled out.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!