The ad looked suspicious, but Eugen Terente was desperate enough to give it a go. The person who picked up the call told him he’d earn a decent wage picking fruit and sent him photos of what looked like comfortable accommodation in the town of Beja, south-central Portugal.

It was only when he arrived, in the dead of night in July 2021, that Terente knew he was in trouble.

He had handed over his passport to the bus driver, who was supposed to be paid by the man who had arranged Terente’s travel. But when the man turned up, he claimed not to have any money on him and promised to retrieve the documents later.

“I realised what was happening,” Terente, 31, told BIRN. “I felt fear running through my body and I knew immediately that I had to do something.”

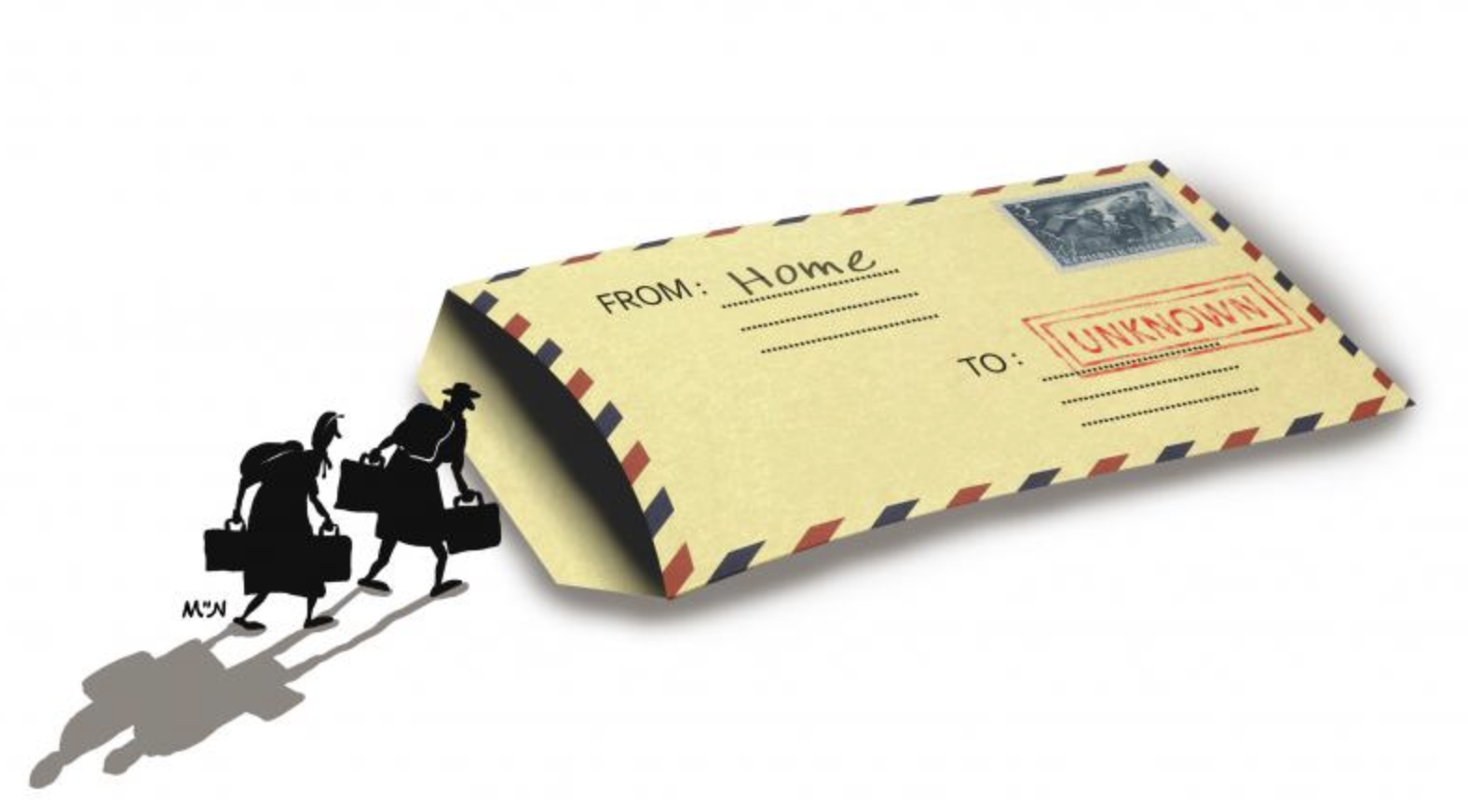

One of Europe’s poorest countries, squeezed between Romania and war-ravaged Ukraine, Moldova is haemorrhaging people in search of better pay and a brighter future abroad.

According to data from 2021, more than a quarter of all Moldovans live outside of Moldova; Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ensuing cost-of-living crisis is driving more to join them. “In our country, 70% of parents say they see their children’s future abroad,” said economics expert Veaceslav Ionita. “In the coming years we will see more young people living abroad than staying at home.”

But while some may prosper, many others like Terente are falling victim to fraud and exploitation.

“Many Moldovans don’t want to go abroad for long periods, but only for the summer months, to work in agriculture and construction,” said Tatiana Fomina, lawyer at La Strada International Centre in Moldova, which helps victims of human trafficking and exploitation.

“But these companies don’t explain that just because you can enter a country for 90 days without a visa means you can work there.”

Unsure of the rules and his rights, Terente agreed to go. Little did he know he’d end up racing through the fields of Portugal, desperate to get back home.

‘Tip of the iceberg’

According to a December 2020 report by the Council of Europe’s Group of Experts on Action against Trafficking in Human Beings (GRETA), labour market exploitation has become the most important form of human trafficking involving Moldovan citizens, and more Moldovan men than women are being trafficked.

The same year, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM), warned that only six out of 10 Moldovans in France had contracts for the work they were doing; in the UK, only 40% of Moldovan men and 72% of Moldovan women had contracts.

Romanians were among the first to take on agricultural work in Portugal. Since roughly 2015, the same thing has been happening to Moldovans.

According to Moldova’s Prosecutor’s Office for Combating Organised Crime and Special Cases (POCOCS), human traffickers play on several factors, including the social and economic vulnerability of their victims, such as a lack of education or employment opportunities.

The victims are usually recruited via social media, in most cases Facebook or Odnoklassniki, a platform popular in Russia and some countries where Russian is widely spoken, as well as on online ad-publishing platforms.

The vast majority who have contracts sign them in the destination country, meaning they have already made the trip with no guarantee of work or what they will be paid.

Control is then exerted by the “classic methods,” as Moldovan police told BIRN – via the debt the victim owes, confiscation of their ID, the language barriers and, in some cases, violence or the threat of violence.

Moldovans interviewed for the IOM’s report said that in some countries, such as Israel, France, and Germany, they were told a verbal agreement was sufficient, leaving them almost helpless when it comes to proving breach of contract.

Trying to address the issue, Moldova opened the Male Victims Assistance Service in 2021 as an offshoot of the Assistance and Protection Centre for Victims and Potential Victims of Human Trafficking; the previous year, the Centre assisted 14 victims of exploitation in Moldova and abroad.

“Most often, Moldovans are exploited in Portugal, Spain, and Germany”, said its director, Nadejda Radu. “It depends a lot on the boss; if the boss was from a post-Soviet country, most often people will not receive employment contracts.”

Fomina, of La Strada, said that Moldovans from rural areas, with lower incomes and only basic education are more vulnerable to exploitation. But, in fact “anyone can be a victim”, she added. “Not all cases are made public; we only see the tip of the iceberg. Most of the time people think they were unlucky and will be luckier next time.” […]

A dash for freedom

In Terente’s case, he was told that the company was registered in European Union member Romania but operating out of a private house in his hometown, the Moldovan capital Chisinau.

It was there that Terente was told he would be paid between 30 and 40 euros for eight to nine hours work a day, picking melons, watermelons, and olives in Portugal. The minimum wage in Moldova as of April 2020 was roughly one euro an hour, and though the government promised to almost double this from January this year, it’s still 1.15 euros. That’s still far less than what Terente was told he’d earn. His only obligation was to reimburse the company from his salary for the cost of issuing the documents he needed.

“But they gave me nothing,” Terente recalled. “In fact, I was left in debt.”

Already without his passport, Terente recalled arriving at his accommodation, where the first thing he saw was women sleeping on a mattress on the floor.

The rooms and facilities were dirty, the doors broken; some people were drinking. Terente only spoke Romanian and Russian, yet he understood very well what was going on. He spoke to no one and tried to get some sleep.

At dawn, Terente made a run for it through the surrounding fields with another man. After about 35 kilometres, they reached a police station, where he was advised to call the Moldovan embassy.

Terente did so, and was told he would be helped, but he also called a man he had met on the bus to Portugal, another fruit-picker working for someone of Romanian origin in the same area. They managed to link up and Terente began work for his new boss, on a promise of pay and help to get back his passport.

The conditions, however, were the same, and after a week of work Terente realised nothing was happening on the passport front. “So I called my brother to tell him about my situation.”

Terente’s brother in Chisinau began working the phones and, after much effort, managed to secure a temporary travel document from the embassy to bring him home. Moldova’s foreign ministry contacted Portuguese authorities, who launched an investigation.

Alberto Matos, of the Solidariedade Imigrante NGO, said that for years he has witnessed Moldovans arriving by bus to Portugal, ostensibly as ‘tourists’ full of hope but destined to leave disappointed.

“You can stay in Portugal with a Moldovan passport for 90 days, and that may be enough for an agricultural campaign,” he said.

“For a long time I have seen buses coming. And when one arrives, someone is coming with a smaller bus to pick the people up and they take them to the countryside, to some isolated houses, where those people end up being exploited.”

According to the Prosecutor’s Office in Moldova, in the vast majority of cases, the recruiters are Moldovans and their companies do not have licence to employ people abroad nor cooperation contracts with foreign employment agencies. In 2021, prosecutors pursued 65 criminal cases of human trafficking, resulting in 55 convictions. The victims are more often men than women.

Male victims ‘don’t ask for help’

Terente may have spoken out, but many other Moldovan men with similar and worse experiences suffer in silence.

“Many men think what happened is their fault and don’t ask for help,” said Alexandru Donos, a psychologist at the Male Victims Assistance Service. “They don’t want to cooperate with the legal authorities. These misconceptions and prejudices lead them to conceal the situation they have experienced.”

Few can have confidence in the Moldovan authorities. The US State Department’s 2022 Trafficking in Persons Report cited corruption in the justice system as an acute impediment to bringing traffickers to justice.

Responding to the case of Moldovan workers in Portugal, the foreign ministry said its diplomatic missions stand ready to provide consular assistance and that it would closely monitor reported cases of exploitation and seek dialogue with local authorities.

Terente said he had not expected to get rich; “I just wanted to do something different. I wanted to see what it was like in another country,” he told BIRN. “But I realised how wrong I was when I felt the fear in my body, even after I got home.”

👉 Original article on Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN)

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!