Zanyar’s dream of a life beyond his hometown Zurkan, near Ranya, Iraq, cost his family €11,000, his father’s land and, ultimately, cost him his life.

According to a local migrants’ association, between 2020 and 2021 alone, over 56,000 people from the Kurdistan region of Iraq decided to migrate due to geopolitical instability and lack of opportunities – 20-year-old Zanyar was one of them.

“Zanyar dropped out of school,” Mustafa Mina Nabi, Zanyar’s father, recounts as he tended to the roses in his garden outside his cement-made home in Zurkan. “He said that others who graduated couldn’t find a job either. And without a job, how was he going to settle down, get married, start a family?”

Zanyar wanted to reach the United Kingdom and establish himself as a barber. But his dream came to an end in the cold English Channel, on a stormy day in late November 2021.

Zanyar was among the two dozen people seeking refuge in the UK who died of hypothermia when their dinghy sank whilst trying to cross from northern France to southern England. Reaching Europe and the United Kingdom via the irregular route is not only difficult and dangerous, but also extremely expensive.

The absence of legal migratory routes has created business opportunities for criminal networks. It has also increased the role of an informal banking system that works through “hawala”, a millenia-old traditional money transfer system based on interpersonal trust.

This joint investigation, carried out over 2022 by a team of six journalists, exposes how tightening migration policies have caused migrants to fall prey to unscrupulous smugglers, and trust hawala as the only way to mitigate the risk of being scammed.

Hawala: a system based on trust

On a cold morning in late November 2022, in Erbil’s Money Exchangers Market, known as the “US Dollars Bazaar” in the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, vendors move around with blocks of banknotes the size of an old-fashioned TV box.

Men shout out large sums of money – US dollars, Iraqi dinars, Syrian pounds – which they offer to exchange to the highest bidder. Money constantly switches between hands.

Dozens of money-order offices populate the streets, corridors, and basements of the bazaar. Some work with Iran, and others send money only to Germany and France. Some have partners all over Europe, while others claim they can send money to any country in the world. But, instead of the usual channels of international banking, many use the “hawala” system.

In Turkey, the hawala is often run through an exchange money office. In Greece, the hawala broker can be the owner of a mini market or a shop selling mobile phones. In Belgium, it could be any of the three options.

A hawala broker’s office can be as simple as a desk and a chair, a mobile phone, a money counter machine, and a safe box. A notebook also comes in handy to keep track of debts.

There is no SWIFT or blockchain system to record transactions, nor do hawala brokers provide any kind of receipt that secures the debt. The system relies mainly on trust, Gözde Güran, an assistant professor at Georgetown University, explains. “By knitting together different trust relationships, hawala brokers are able to simultaneously use the trust to guarantee their mutual obligations and extend their coverage across multiple locations.”

In the case of smuggling, there is a further benefit. To provide guarantees of passage to people on the move, hawala brokers pay out the reserved sum to smugglers only after they have successfully reached their destination.

A hawala broker “would not ruin his reputation” by swindling a migrant, says Mustafa, Zanyar’s father: “Here we are from the old school. If he did something like that, no one would do business with him again.”

In Zanyar’s case, the hawala broker refused to hand the money over to smugglers after his death and instead returned it to his family; small compensation for the loss of their beloved son.

The rising importance of hawala for migration

The system is as old as the Silk Road, when it was used to facilitate payments between merchants, preventing them from carrying large sums of money on their long journeys.

Today, money transfers through hawala are particularly popular across the Middle East and South Asia. For many migrant communities, it is also a standard system for sending remittances home, especially to countries like Iran and Afghanistan, excluded from the global financial system.

While commissions of companies such as Western Union or Moneygram can reach up to 15%, hawala brokers charge anywhere between 2% and 10%. Sometimes “it can even be 0%”, explains a hawala broker from Erbil, if the transfer requested helps settle a debt in an address where not many shipments are usually made.

The system is also not new to the payment of migration routes which, according to estimates based on data from UNHCR, Europol, the European border agency Frontex, and expert reports, bring in a collective annual turnover between €300 and €700 million.

Over a million people arrived in Europe in 2015, in what has been recorded as the peak of the ‘refugee crisis’. Europol estimated that half had paid for their journey in cash; the rest by various methods, including hawala.

For many migrants, this is the only trustworthy system to make payments since it provides security and prevents being cheated by smugglers or robbed by criminals or border guards. “Nobody carries big sums of money nowadays,” a middleman who connects migrants and smugglers explained from his travel agency in the center of Ranya, in Iraqi Kurdistan. “It’s a service… The best one so [as to ensure that] at least people are not scammed.”

He was also on the move once in 2005, when he traveled irregularly to Denmark and spent years there until he decided to return home. He then started to participate in the lucrative business of human smuggling.

The increase in pushbacks, across different border crossings of the trip, has made the hawala brokers’ insurance role even more important. As it becomes harder to cross borders, they promise not to pay out until a destination is reached, which provides vital security.

Most of them belong to the same community as the people on the move, according to expert Güran. “Customers normally really want to go to the person from their nationality, even hometown if possible. And they always express so much distrust towards brokers from other countries,” she notes.

Sometimes hawala is referred to as a “shadow banking system”. But according to Güran, that depends on how government and legal authorities view it. “I understand that governments are worried about unregistered individuals conducting money transfers because this doesn’t fit into their surveillance security paradigms of today and they are not able to trace these transfers, which can reach significant amounts,” she said.

“However in many contexts, it is the only system people know because there is no other way to pay suppliers or finance any kind of operation,” she added.

The road starts on WhatsApp and Telegram

Smugglers use WhatsApp and Telegram to advertise their services and gain the trust of people on the move. Over the course of this investigation, the reporters joined 13 Telegram groups where smugglers connect with migrants.

The groups provide information on prices, details about the payment, and phone numbers where one can call for additional information. Messages are typically deleted within a few days.

Administrators referred repeatedly to “codes” and “decoding”; a reference to the passwords used to unlock money at a hawala broker when a checkpoint along the journey is reached. One smuggler promised: “We have a way to Serbia through Bulgaria. 5 hours walk to the charging point […] In case of fingerprinting in Sofia, code decoding XXXX.”

Where is the money?

Once received by smugglers and hawala brokers, there is no way to track the money, making the system beneficial to hide illicit profits from authorities.

Alaa Qasim Rahima, known as “Abu Al Awl”, a Kurd born in Iraq in 1984, knows it well. When he was living in a refugee camp in the Netherlands, Abu Al Awl used to sell food in a “black market”. Later on, he moved to Italy and started to work as a smuggler: he could make arrangements for people to cross the Balkans or Italy to reach France, Germany, or other destinations by simply using his smartphone.

Now, as he sits detained in an Italian prison, standing trial for allegedly smuggling migrants from southern Italy to the rest of Europe, investigators have not been able to put their hands on his “treasure”.

“For each migrant, I asked for around €500-€600. The sums were deposited with agencies in Turkey, where they still are,” he explained, in November 2022, before his trial. He claimed his money in Turkey amounts to nearly €300,000.

“Recent police investigations have highlighted the very important role played by [the agencies] in favoring illegal immigration towards the countries of the European Union. Not only do they practice the so-called Sarafi (or hawala) method, but also act as ‘agencies’ for the recruitment of migrants eager to reach Europe,” the Guardia di Finanza (the Italian law enforcement agency dealing with financial crime and smuggling) writes in a report.

The investigators also underline another aspect: “The owner of the agencies chooses the best organised and most reliable smuggler” because “only the successful outcome of the transfer of migrants guarantees the hawala broker the collection of the percentages on the fees due to the smugglers.”

Hawala’s vague legal status

In reply to a parliamentary question on July 31, 2020, Valdis Dombrovskis, EU Executive Vice-President responsible for an Economy that Works for People, stated: “Within the European Union, those that operate hawala, like all operators providing payment services, should be authorized payment institutions, appropriately registered and regulated.”

In the EU the system is illegal, but in some countries, like Italy, clients are not penalized – but hawala brokers are. In others, like the UK, some hawala brokers are registered and regulated, while others operate out of sight of the law.

“We must be careful to not present the hawala as a criminal activity because, in some countries like Austria, it can be legal if you register with the authorities. Not many do register though, and they may not know about the requirement to register,” says Dr. Claire Healy, coordinator of the Observatory on Smuggling of Migrants, established by the UNODC, who is working on research about the “abuse” of the hawala system by migrant smugglers. The researchers interviewed 113 hawala brokers in 30 countries (in Asia, Africa, Europe, and North America).

In October 2022, the second day of the “largest meeting ever of prosecutors who specialize in tackling migrant smuggling,”( as its organizers, the European Union Agency for Criminal Justice Cooperation defined it), was dedicated to the financial streams behind migrant smuggling groups, including “the use of the alternative hawala.”

In a report, the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) – the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog – points out that hawala is “the most common method of transferring funds (often cash) generated from migrant smuggling,” adding that this makes it “extremely hard for Financial Information Units and Law Enforcement Agencies to perform financial analysis and investigations.”

There are many reasons. “Financial flows are often channeled via hawala, and in most cases from and to countries with limited capacity or experience in conducting cross-border financial investigations,” the report states.

Moreover, people arrested for smuggling such as drivers “are also generally unable to provide any information.” Just like in the case of Abu Al Awl, “funds that are not seized during investigation remain out of reach.”

Hawala brokers will be the bankers

On a cold and damp January morning in 2023 in Grande-Synthe, a coastal suburb of the French city Dunkirk, refugees wait for a chance to cross the English Channel.

In a cluster of blue and white tents that line a railway line, Aisha* and her two little daughters huddle together around a fire near the track, trying to keep warm. She plans to cross the Channel soon, hoping to join her husband who has already applied for asylum in the UK.

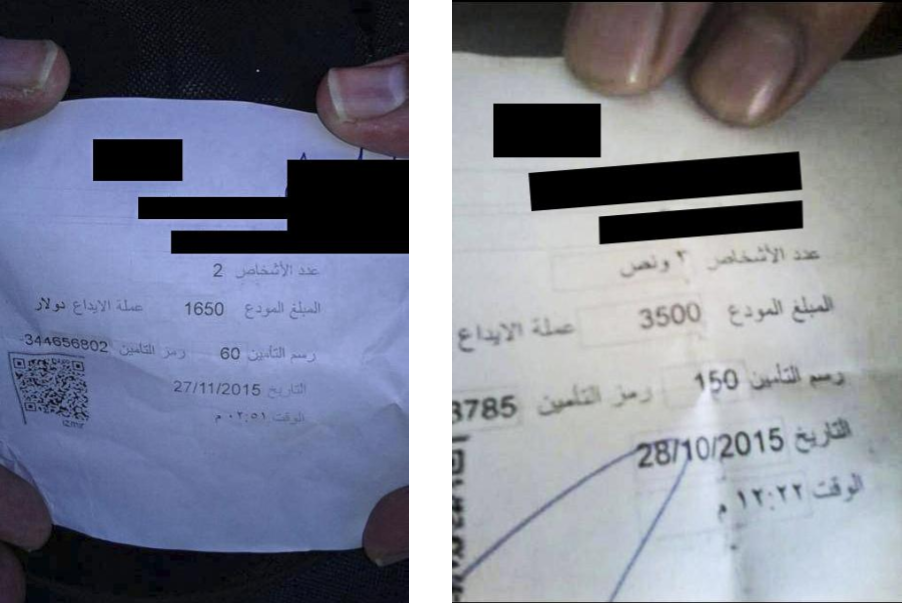

So far the journey – from Iraq to Turkey on a tourist visa, then through the Balkans, to Croatia, and France – has cost €4,500 for the three of them. Aisha expects to spend another €1,500-€2,000 to cross to the UK by boat. Her father paid for the journey via a hawala broker in Iraq. “With every border I have crossed, I send my father a WhatsApp message with my location and he alerts the Nosinga (a Kurdish word for the hawala broker) so that payments can be made to the smuggler,” she said.

“I am a journalist and fleeing because I was being targeted for my work back home,” she said.“I couldn’t get a visa to come to Europe legally and have had to seek refuge through this dangerous route where the smugglers are ruthless.”

“Since we don’t have the option to come legally and need security, hawala is what we have to resort to,” says Goran, a 19-year-old Iraqi-Kurdish man who is also waiting in Dunkirk.

A Kurdish man from Iran joins the conversation: “The EU should take action to change this by giving more visas. Even if they tried to tackle hawala, people will still find a way to cross.”

While European and international police authorities are trying to understand how the hawala system works in order to tackle smuggling, for the thousands of people on the move making their way across Europe, hawala’s legality is irrelevant. And as smuggling remains the only travel route, hawala brokers will be its bankers.

*Some names have been changed.

👉 Original article on Solomon

Supported by Journalismfund Europe

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!