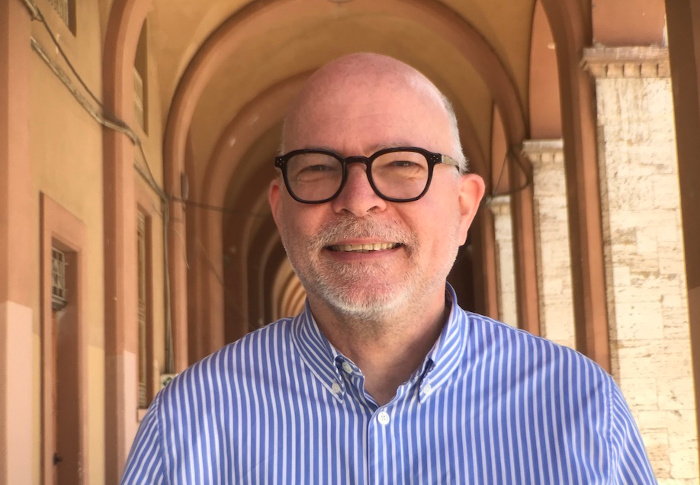

Paul Nemitz is Principal Adviser in DG Justice and Consumer Protection of the European Commission and Professor of Law at the College of Europe. He is considered as one of Europe's most respected experts on digital freedom and has led the work on the EU's General Data Protection Regulation. The English translation of his essay The Human Imperative – Power, Democracy and Freedom in the age of Artificial Intelligence, co-authored with Matthias Pfeffer, will be published in June of this year.

Voxeurop: Is Artificial Intelligence (AI) an opportunity for democracy or a threat to it?

Paul Nemitz: Alarmist voices are increasingly replacing naive optimism about AI. Both Elon Musk and Bill Gates have said that AI is like nuclear power, an opportunity and an existential risk. In his book Human Compatible, Stuart Russel, author of the best-selling textbook on AI, describes the problem of controlling AI. He draws a parallel with nuclear power: We cannot be sure that general artificial intelligence will not be achieved by tomorrow. There was a time when all the leading scientists thought that splitting the atom was impossible. All this calls for democracy to take control of this technology, according to the time-tested precautionary principle.

Responsible engineers and developers will not disagree. Neither the individual nor democracy can be controlled and manipulated by AI. On the contrary, individuals and democracy must remain in control of AI. Whether we can make AI an opportunity for democracy depends on many factors. First and foremost, the willingness of those developing AI to serve democracy and not just to make a profit. Second, a willingness to invest in AI specifically designed to empower democratic actors – from parliaments and governments, political parties, media, trade unions, NGOs and churches to individuals – to contribute more actively and constructively to the functioning of democracy.

Should the EU regulate AI, and if so, how and in what direction? Does the AI Act address the main issues related to AI and its use?

We cannot leave this technology to self-regulation and ethics alone. Like chemicals, cars and nuclear power, to name but a few examples, this technology is important enough to require a law to define its direction and limits. The AI Act will be an important precedent confirming the primacy of democracy in times of rapid technological development. The cheap calls for self-regulation and ethics rather than binding and enforceable law are outdated, because the power and speed of technological development simply require law to ensure that the public interest is served and that everyone, including those who do not want to play, is actually bound by rules that are enforceable.

We cannot ignore the important issue of power when discussing AI. Without binding law, the power of technology to shape society lies solely in the hands of those who develop and own it. If society were organised in this way, democracy would not work, nor could we ensure respect for fundamental rights. The EU's internal market also needs a regulation, because without a law at EU level, we would soon have a fragmentation of legislation across 27 Member States and thus no functioning internal market in high technology. The EU’s AI Act addresses many important issues related to the development and use of AI and, like everything in democracy, will be an act of compromise, a compromise in the right direction between different political world views.

Under the current draft legislation, AI tools will be categorised according to their perceived level of risk: from minimal to limited, high and unacceptable. Areas of concern could include biometric surveillance, spreading misinformation or discriminatory language. Does this make sense?

The risk-based approach to regulation is a good start. But it is limited because it reduces legislation to a repair shop for market failures and technological risks created in the private sector. So, if we only had risk-based regulation, democracy would be abandoning the aspiration that people, through democracy, shape their societies and the way they want to live. That said, the AI Act is part of a holistic package of first-generation legislation with which the EU is shaping the new digital realities. It stands alongside the Digital Services Act (DSA), the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and consumer protection legislation, to name but a few pieces of legislation already in place. It now needs to be adopted quickly to create facts.

The more than 3,000 amendments in the European Parliament show that democracy has a lot to say about AI and its regulation. And that it works well in Europe. I believe in the willingness to compromise in order to pass legislation and show that democracy can work. In this spirit, I believe the AI Act, together with other laws already in place that also apply to AI, is a good first piece of democratic legislation on Artificial intelligence, binding on both the private and public sectors. We can be proud that Europe is once again ahead of the game on this important issue of putting democracy before new technologies.

Can we trust the Silicon Valley tech giants engineers and moguls for self-regulating Ai? The recent call by a few of them to pause Ai’s development is going in the right direction or should governments (and the EU) intervene. Should there be a worldwide regulation, to have everyone playing on the same level field?

We certainly cannot trust self-regulation in areas of great importance to individual rights and the good functioning of society. Even the freedom of the press and the protection of journalists in Europe are based on strong laws. The idea that the best and freest society exists in the absence of laws is simply foolish. On the contrary, the noblest expression of democracy is the making of laws. We must stop talking about the law as a problem, as a cost, as an obstacle to innovation.

Experience with climate change and nuclear power shows that the opposite is true, and this lesson also applies to the digital economy, which now largely dominates our public sphere: Only strong laws, based on good democratic processes and with strong enforcement mechanisms, can safeguard the public interest in complex societies. As for global regulation, we see a lot of activity in the OECD, UNESCO and the Council of Europe. But we cannot wait for global agreement, because our democratic process cannot and should not depend on the agreement of others. Having said that, Europe does of course seek global understanding and, where possible, international law-making. We want a world based on rules, not on power.

EU and/or US regulation would in any case leave room for rogue states or governments to use AI for military or disruptive purposes. What are the risks?

The aggressor Vladimir Putin has said that whoever controls AI controls the world. There is a technological race to use AI for military purposes. It is important that NATO is not overtaken in this race by either Russia or China. Discussions on international rules governing the development and use of AI for military purposes are progressing very slowly, for obvious reasons. But there is certainly an ambition among democratic states to come up with rules for military AI similar to those that exist for landmines, small arms and even nuclear weapons. It is more likely that we will arrive at good rules from a position of strength than from a position of weakness. But it would be a mistake to use this argument to demand a free-for-all for the development and use of AI by businesses in the civilian sector and by governments for non-military purposes. The challenge of making AI supportive of democracy and fundamental rights is a technological challenge to be met by developers, not an obstacle to development.

What do you think about Elon Musk’s XAi? Is there a risk he will misuse it like he is doing with Twitter?

Elon Musk is a player in the attention economy. I do not know where his XAI is going and it is not the most important thing to know. But one thing is clear: Elon Musk and his companies must be held accountable to the law at all times, just like any other natural or legal person.

How can we make Ai companies accountable for their products’ possible misuses or getting out of control?

The Commission has proposed legislation on liability for AI. And the AI Act sets out the standards of care that AI developers and users must follow.

Do we need ethical rules, in addition to legal ones, for AI and its use by media companies and others? If so, what should they be?

There is nothing wrong with ethical rules in addition to legislation. The engineering profession has a long tradition of setting ethical rules for its individual members, and individual engineers often have higher ethics than the companies they work for. But what does not work is replacing the law with ethics or self-regulation. The first rule of ethics in any technology company must be: We obey the law, and we obey it front and centre. So no games on the fringes of the law, whether it's tax law or AI law. Those who think that disruptive innovation includes disrupting the law should feel the hard hand of democratic law, because in essence they often disrespect democracy simply out of self-interest.

In your book The Human Imperative: Power, Freedom and Democracy in the Age of Artificial Intelligence, which you co-wrote with Matthias Pfeffer, you say that "Digital technologies and their corporate masters now know more than people know about themselves, or governments know about the world. […] Taken together this leads to a massive asymmetry of knowledge and power in the relationship between man and machine." Will Ai lead to less inequalities or, on the contrary, will it deepen the knowledge and power gap between those who control and master it and those who don’t – always the same? Who will protect the latter and how? In your essay, you also mention some possible solutions.

Public policies need to ensure that technological progress benefits all people and is conducive to the good functioning of democracy. This requires a holistic policy mix and cannot be achieved by a single measure. We need to constrain the powerful and avoid concentration of power, we need to empower new entrants and we need to empower people in their daily lives. This policy mix of regulation and industrial policy, including public funding, is what political decisions in democracy are all about. Just as in the EU we need broad majorities to pass laws and budgets, so EU policy on these matters is a mix of the different worldviews of democratic parties.

‘We must stop talking about the law as a problem, as a cost, as an obstacle to innovation’

As the majorities change, so does the content of the policies. That is why it makes sense for interested people to engage rigorously and over the long term in the democratic process, which is much more than just elections. Anything that can be done with and through AI to increase such engagement with representative democracy and its actors is welcome. It is now time for the major players in AI to move beyond lip service and invest in making this happen. We need tools that facilitate people's sustained engagement in democracy, that empower individuals in relation to the powerful, such as big business and big government, and that help people organise together and relearn the painful processes of making decisions together, whether in political parties, churches, trade unions or large NGOs.

A recent report by Goldman Sachs says that generative AI will eventually lead to the elimination of up to 300 million jobs around the world in the coming years. Do you agree? What is the upside?

The policy of precaution means that we must take such studies seriously, even when their predictions differ widely. Many new technologies require new skills and policies to help companies and people through the structural changes that lie ahead. This is the EU's policy. Democratic governments and the democratic EU cannot stand by and watch democracy, the rule of law or good jobs and employment go down the drain as AI and the corporations that dominate its development and use take over.

We are actively engaged in policy making to avoid the downsides of the digital age and to make the best of it for people individually, but also for the good functioning of our societies. A "frank discussion" in the White House with tech leaders about the risks of AI, which we could read about in the press, is good. But getting a law on AI and liability for AI through the democratic process is even better. It's not a bad thing that Europe is leading the way in making democracy work in the age of AI.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!