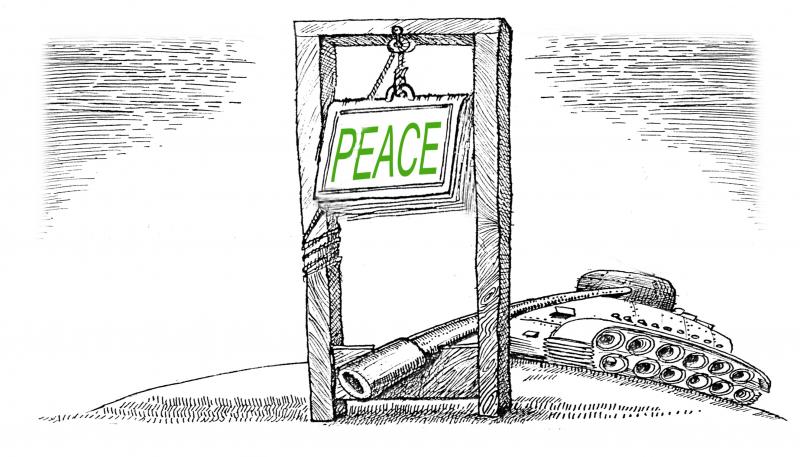

I have decided to address two questions that continue to puzzle me: What can literature do to dismantle structures of violence? And why do we still need the peace movement?

My interest in peace, ecological issues and the deconstruction of structures of violence stems from my own life experiences. Until I left home at the age of 15, I lived in a household where the war traumas of men who had fought on the front lines of both World War II and the Lapland War were constantly present and part of daily life. Men who had been psychologically broken at the front vented their anxiety and rage at home. Their fury affected humans, other species as well as the surrounding nature.

The operational logics of aggression and violence internalised in wars, intertwined with silence, are passed on from one generation to the next. Today, the results of these patterns of behaviour can be observed in clearcut forests, drained swamps, open-pit mines and polluted waterways.

The legacy of war trauma runs deep in Finnish society. Having lived through this, I joined the anti-Vietnam War movement while still in secondary school and later, in high school, became involved in the peace and environmental movements.

Committed literature

In 1947, Jean-Paul Sartre, the philosopher who survived the horrors of World War II, asked his contemporaries, especially the authors, to take a good look in the mirror. He called for a "committed literature" – littérature engagée.

Not to tame the authors or make them the servants of political tendencies and movements, but simply to face up to the total degradation of western civilization and the complete corruption of Enlightenment values taking place at the very heart of Europe in the wake of Auschwitz; to encounter that reality with honesty.

Now, in 2025, when we look at the world, we must ask ourselves how far we really are from that post-war decadence that Sartre observed.

In 1955, ten years after the USA had destroyed the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the philosopher Bertrand Russell published a petition against nuclear weapons. The most prominent person who signed Russell's manifesto was the physicist Albert Einstein. The most important part of the petition is this one:

Here, then, is the problem which we present to you, stark and dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race; or shall mankind renounce war?

When Finland in 2023 joined NATO, the world’s largest military alliance, our leaders emphasised that the deterrence of NATO is based on nuclear weapons. Now that Finland is a member of NATO and the placement of the nuclear arms on Finnish territory is no longer considered impossible, politicians have started to use the term "nuclear shield".

The balance of terror maintained by this shield does not in any way consider the fact that in a nuclear war, entire nations, animals, forests, water systems will be annihilated, and the air that we breathe polluted.

The UN Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, which entered into force in January 2021, aims at exactly that. None of the countries that have nuclear weapons or is a member of NATO, Finland included, has signed the agreement. In fact, both Russia and the USA, as well as Israel, India, and Pakistan, even leaders in Germany, France and the UK, have recently raised the possibility of a limited nuclear war.

And yet, we all know that a nuclear war would result in climate disruption and global starvation. It will be the end of civilisation. The only way to prevent nuclear war is the complete destruction of nuclear weapons.

US Republican President Dwight Eisenhower warned as early as 1961 about the dangers of the growth of the military–industrial complex. He was referring to that the military, political and economic powers are intricately intertwined and together form a threat to peace and democracy.

We have ended up living in the time that President Eisenhower warned us about.

‘Violence originates in language’

Militarisation of discourse and the way that talk about security and defence has become part of our everyday lives continues to chip away at democracy. According to war researcher Susanna Hast "Violence originates in language – it is conceptualized, strategized, and initiated through discourse." The use of euphemistic terminology, such as referring to war as a "conflict", "the fight against terrorism" or "the liberation of territories" serves to obscure the true nature of events.

Once war has been brought into everyday language, fighting becomes a natural extension of our words.

We live in a time when the world order created after World War II is falling apart. The global powers are currently breaking away – or have already broken away – from democracy. Now, in 2025, we can ask ourselves what we have learned from World War II, what have we learned from history in general? All our actions, here on our planet, have a global impact and we need global institutions to solve these. Global institutions, which are currently undermined by those great powers.

Acting in a peace and ecological movement is nowadays regarded as an idealistic delirium, something from the past. In fact, both the peace movement and the ecological movement are needed more than ever. They are needed to remind us that militarism is a choice – a choice for vast ecological destruction, a choice for ecowar. These movements are needed to demand that international justice is upheld and further developed.

They are there to promote the establishment of demilitarised zones and call for the destruction of nuclear weapons. For maintaining the belief in world peace and non-violent action. And, finally, we need the peace movement and the ecological movement to strengthen a kind of communication that respects the principles of a democratic society.

We need to remind ourselves that every person's contribution to the peace movement, and to ecological action that will help in this process, is meaningful. Change often start from small movements, Tiny streams that converge to form a great river. For example, the civil movement against the Vietnam War or the courage of Gandhi's pacifistic movement to resist one of the world's biggest colonial powers both changed the course of history.

I, as a committed writer, aim to uncover the roots of violence and illustrate how literature can actively contribute to finding a counterbalance

Today, people's movements such as Elokapina, the Extinction Rebellion movement in Finland, the global climate movement, other environmental and peace movements, the Ecocide movement, and feminist scholars researching militarism all act as counterforces to destruction.

Considering that the current emissions from warfare and the military–industrial complex are among the most destructive to the environment, I, as a committed writer, aim to uncover the roots of violence and illustrate how literature can actively contribute to finding a counterbalance.

My focus is on reshaping the narrative of a human being who champions militarism and the survival of fittest, on re-contextualising such a person's existence within the broader web of life, which includes all species.

Violence and exclusion, and literature

Although the setting of my novels is historical, writing them has always been motivated by the burning questions of the day. How to share the experiences of violence and exclusion through literature? How to rewrite human reality and man's place in nature and among other species? How to find a breathing connection to the layers of our existence that human-centred modernism has tragically lost over the past centuries? How to compose the literary narrative to reveal the simple truth that we have so stubbornly denied for such a long time: that nature does not need man, but man needs nature?

The art historian Anita Seppä emphasises that "we live at a pivotal moment in history, when the power to redefine our future still lies within our grasp. The green transition is not sustainable if we do not swiftly connect environmental efforts with long-term peace building and diplomacy. This endeavour necessitates radically new ways of envisioning the world within and around us. Literature and the arts play critical roles in this essential reimagining process."

The time to start this transformative work is undoubtedly today.

This is an edited version of the closing speech Rosa Liksom held at the Helsinki Debate on Europe, on 17 May 2025.

© Debates on Europe 2025

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!