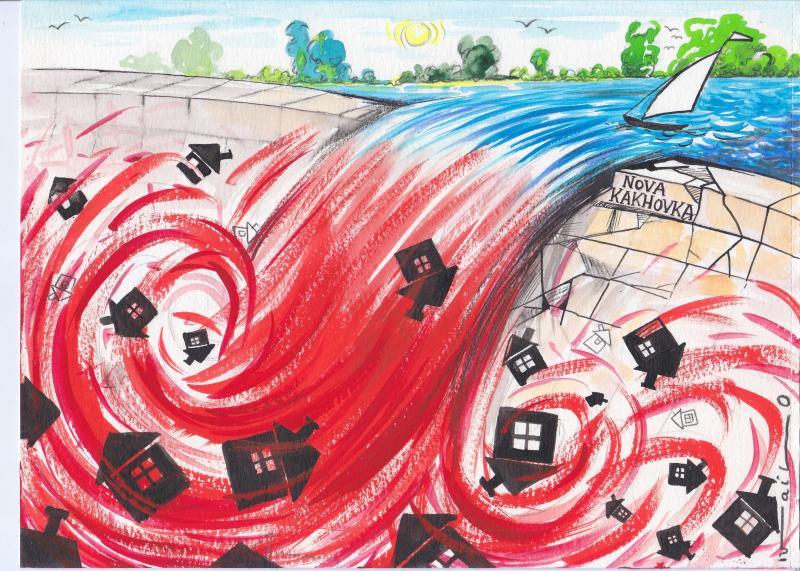

The destruction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power station is one of the biggest disasters to afflict the “civilised world”. The dam held back 18 cubic kilometres. Scientists believe the flow rate at the breakthrough was around 90,000 cubic metres per second, says Serhiy Afanasiev, director of hydrobiology at Ukraine's National Academy of Sciences. In the first 3 days, the Black Sea received about 100 times more river water than it normally does: a tsunami that swept away everything it encountered downstream of the dam, including houses, people and animals.

The dead stuck out of the water like candles

Novyi Den, which resumed publishing in liberated Kherson in November 2022, spoke to a resident of Oleshky, a town at the epicentre of this man-made disaster. Natalia Vozalovska miraculously managed to get out of Oleshky: “The civilian population of the occupied town learned that our reservoir, one of the world's largest, had burst its banks as a result of the dam's destruction. They heard about it from the TV, or from their friends on the phone. No one was warning about the scale of the danger. That's why people were not particularly worried. They did not think that there would be such a horror! However, at one point a car with a loudspeaker drove down the street. They said that if anyone wanted to evacuate, there would be buses near the fire station. But we never saw those buses. Already on 6 June, Oleshky was flooded.”

“The water, very smelly, full of fuel oil, was raging! People were getting into boats, and they were overturning. The elderly and disabled who lived closer to the Dnipro River could not get out because the water immediately blocked the doors of their houses”, Natalia adds. “This is how our neighbour, who hardly ever left the house, died. And there are a lot of such terrible stories. Many people climbed into the attic. The houses, which were made of reeds and adobe, collapsed straight away. People were falling down together with the attic. That's how the roofs of the houses floated. And in Solontsi, they say, the occupiers did not allow people to get out of the attics. There were screams, cries for help... I will say this: if you watch the film Titanic, it was much worse here."

As she speaks, Natalia is unable to control her emotions: "Those who managed to escape fled in whatever they were wearing. People from the non-flooded part of the city took them in. In those days, there were 10-12 people living in a house. They shared clothes and food. We took what we had to the market and gave it away. My husband and I had a small rubber boat. My husband said: let's inflate it just in case. And so the boat was inflated. We threw in a bag with documents, a first-aid kit, drinking water in it... The yard started to flood very quickly! In just ten minutes, the water was already above our knees. We barely had time to open the gate to get the boat out. We saw people dragging children and animals, saving whoever they could. Many people did not untie their dogs when they were running away... Cats were scrambling up the chimneys. Many dogs drowned. All the time there was heavy bombing of Oleshky. The forest was burning... What the occupiers could not drown, they tried to burn or bomb. We survived this horror with good people in the non-flooded part of the town..."

Interesting article?

It was made possible by Voxeurop’s community. High-quality reporting and translation comes at a cost. To continue producing independent journalism, we need your support.

When asked how the occupiers and their "administration", which was supposed to take care of the civilian population, behaved in the city at that time, Natalia explains: "The soldiers took away people's boats to escape themselves. But not all of them were lucky – the boats would overturn and some of the occupiers drowned along with their ammunition and weapons. Among the victims were many newly arrived Russian soldiers, whom no one rescued. And the occupation ‘authorities’ of Oleshky were evacuated from the town before the flood. Once I went to the market and heard some women crying: 'Who to go to, what to do, how to clean up the drowned?' The dead were sticking out of the water like candles... In Oleshky, local men who still had boats collected the dead and took children and the elderly to the hospital. Then the occupiers banned the collection of drowned people. It was terrible!"

People saw that the invaders wanted to hide the consequences of the tragedy. Natalia recalls: "When the water receded, the occupiers came to the streets to check. They wrote on the fences in Russian: 'No corpses'. They did this for their own people, so that they could see where the inspection had already taken place and where the dead had been taken from. But they could not go everywhere. There could be dead people under the rubble. Eyewitnesses also said that the occupiers dug up and took away the bodies of drowned people whom the locals had managed to bury. For some time, there was a persistent smell of burnt tyres and a corpse stench in Oleshky. When the left bank is liberated, many more horrors will surface."

“The water stayed in the city for two weeks. When it subsided, the survivors began to quietly return to their homes to see what was left. People would come to their yard, stand there, cry, and leave”, Natalia continues: “They would take a bicycle or a trolley with them to look for what was left. We joked bitterly: we are going to an archaeological dig, maybe we can salvage something... It's just so scary: there's nowhere to live and nowhere to die! We had a mortar house, but on clay. When the water entered the house, all the partitions were damaged. Things were under stones and silt. The furniture fell apart, photos were lost... We were unable to take anything. We lost our house. There is nothing to repair. We just have to demolish it and rebuild it. But we are not of that age any more... I don't know how many years, maybe even decades, will pass before the city recovers. We left, but there are people who cannot. Some have no money, others have relatives who are sick. I don't know how people are still holding out on the left bank. But I want to say: they are waiting for liberation. And so are we. I will say more. In my backyard, the rose bushes, blackened by the flood, have begun to show small leaves. I cut off the dead parts - and I can't believe it but the roses came back to life. It will be the same with Oleshky."

Ghost towns

The exact number of civilian casualties on the temporarily occupied left bank of the region is still unknown. Volodymyr Shlonsky, a doctor from Oleshky, recounts: "Already on 9 June, I was informed about more than 90 corpses in Oleshky alone. (...) we are talking about hundreds of people."

The occupation authorities of Kherson region claimed only 48 deaths on the left bank of the region. However, according to numerous witnesses, this figure is false. According to Ukraine's general staff, in order to conceal the real number of victims, the occupiers buried the dead in mass graves without taking DNA samples or marking the gravesite. Volunteers believe that up to 200 people died in the Oleshky community alone.

In Stara Zburyivka of the Holoprystan district, 202 residential buildings were flooded or submerged. Viktor Marunyak, the village mayor, explains: In the Nova Kakhovka district, the worst affected by the flood were the village of Korsunka and a dacha cooperative located next to it, which is popular among the town's residents. Nova Kakhovka's mayor Volodymyr Kovalenko says that "Korsunka is now a ghost village": "Most of the houses here are destroyed or uninhabitable. There is no electricity or water supply. Almost all the people have left – some to the surrounding villages, some managed to escape to Europe through Crimea and Russia. The coastal part of the village of Dnipryany was also damaged by the water."

The destruction of the Kakhovka dam resulted in 150 tonnes of oil leaking into the river. Thousands of hectares of forest were flooded, killing or imperilling large numbers of birds and animals.

The villages and towns located on the shores of the vanished Kakhovka reservoir are facing a shortage of fresh water. According to Igor Pylypenko, professor of geography at Kherson State University, more than 400,000 hectares of land in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia regions are without irrigation and drinking water. "I put the environmental impact of all these factors in last place", he says. "It will be a disaster above all for the people who live there. Nature will survive such things, but the arid south will no longer have the advantage of growing high value crops. Approximately 400,000-450,000 people in this area will not have access to drinking water, will not be able to engage in irrigation and, consequently, will not have jobs."

Kakhovka reservoir: to be or not to be?

By July, a place where the summer sun used to shimmer on water was transformed into a veritable Martian landscape. Ghastly crevices lined a vast expanse dotted with detritus including stumps from a former collective farm garden, old car tyres, a sunken barge carrying grain and watermelons, and so on.

In July, it was officially recorded: "Kakhovka Reservoir no longer exists". This was the grim conclusion reached by experts from the Hydrometeorological Institute of the State Emergency Service of Ukraine and scientists from the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine. What to do? Farmers in the Kherson region and neighbouring Zaporizhzhia, for whom water is like air, are unanimous: the destroyed dam needs to be rebuilt as soon as possible and water supplied to the fields, because without water things will be even worse than they were before.

Before the war, the Dnipro river, and to some extent the Ingults, were used to transform a climatically harsh region from a zone of risky farming into a risk-free one, and indeed into a source of food security for the country. In 2021, the Kherson region's farmers harvested the largest yields since Ukraine's independence – 3.1 million tonnes of early grains and pulses. The region is also considered one of the best in the country for growing melons and vegetables.

"Without the restoration of large-scale irrigation, the lands of our region will turn into a desert. The entire agricultural economy, the region's main sector, will collapse," says Serhiy Rybalko, head of Adelaide Farming Group, member of the Kherson Regional Council and deputy chair of the Agricultural Commission: "Not everyone in Ukraine knows, but let me remind you that one irrigated hectare replaces 2-3 rainfed ones. Thanks to the Dnipro water, before the war, the Kherson region grew the most vegetables in the country – 14% of the total Ukrainian harvest. Irrigation also helped to develop horticulture, viticulture, and rice farming. And let's not forget the production of export products – soybeans, corn, sunflower... What should we do? Give up the land that our great-grandparents handed down to us?"

The opinion of Serhiy Rybalko and his supporters is not shared by everyone in Ukraine, and particularly not by the scientific community. Ivan Moisienko, professor of biology at Kherson State University, is adamant: "The chance to restore the unique Velykyi Luh [Great Meadow] must not be lost! With the disappearance of the Kakhovka 'sea', almost 200,000 hectares of land is returning to the ecosystems of the Ukrainian steppe, meadows and floodplain forests. Nature will restore itself, but it will be faster if we help it."

Mykhailo Romashchenko, a well-known Ukrainian specialist in land reclamation, is of a different mind: "We will not get back the steppe in southern Ukraine that we had in the Cossack times. The land has been ploughed up, and the climate is not the same. Without the reservoir, Ukraine will be left with a lifeless, cracked desert, with dust storms and terrible ecology. That is why the Kakhovka dam needs to be restored. The restoration of the hydroelectric power plant is essential. When it was built, it was not primarily about generating electricity, but about accumulating large-scale water reserves. Without the Kakhovka reservoir, the country will lose a huge resource."

Right or wrong, there is a perceived need for action. And while discussions are ongoing, Ukraine's government has approved a resolution on a pilot project to start rebuilding the Kakhovka dam.

Prime minister Denys Shmyhal provided details during a government meeting: "It is a two-year project. In the first phase, we will design all engineering structures and prepare the necessary basis for restoration. The second stage will start after the de-occupation of the territories where the hydropower plant is located. This phase includes the actual construction work."

Ihor Syrota, CEO of Ukrhydroenergo, the state-owned company that operates the dams along the Dnipro river, adds that new plant will be more powerful: "Before the destruction, it produced 340 MW, and we planned to build another 220 MW plant."

The past is destroyed, and the future will come only with the occupiers gone

118 cultural monuments were destroyed by the flooding of the Kherson region that followed the dam's destruction. According to Oleksandr Prokudin, head of the Kherson regional administration, 102 monuments are located on the left bank of the region, and 16 more on the right bank. The territories of the Oleshky Sich [a historic Cossack polity], the Tyahyn fortress in Beryslav district, and the 18th century monastery in the village of Korsunka were all flooded. Ten libraries and five museums were partially or completely submerged.

In Oleshky, local residents eventually managed to locate the house of Polina Raiko, a local artist and representative of naïve art. It was as they had feared: the flood had almost destroyed the unique paintings on the walls of the house. Most of the artworks have disintegrated or are otherwise ruined.

But not everything is lost. Our long-suffering land has survived many terrible hardships, and it will survive the current one. "The steppes and lakes will come to life", as our great poet Taras Shevchenko wrote. It will happen this time too!