"An East Berliner appears through the frontier crossing, amid the elated crowd. Pale-faced, wearing some kind of a padded jacket, his breath is visible as a frosty plume against the cold night sky. He has just got through. He has probably never set foot in the West in his life. Incredible. Unglaublich! He sees the television camera, looks straight at it, and shouts just one word: Freiheit! Then he is gone. In that instant, the word "freedom", so much devalued and abused, recovers all its pristine, primal force." For historian Timothy Garton Ash, this is "the image to remember" from the night of 9 November 1989, "which opened the door not only to German but also to European unification." As he further explains in The Guardian, a few months later, US president George H. W. Bush evoked the prospect of a "Europe whole and free," an objective that may soon be realized because "today, on 9 November 2009, we are closer to that goal than Europe has ever been in its whole long history. Ever."

Now that it's time to take stock of the impact of 1989, Tagesspiegel wonders how the changes have affected "Germany 20 years on." Can we really speak of "a united country?" In answer to this question, the daily takes the view that Germany's much-vaunted unity is mainly "on the level of appearances." Superficially at least, times have changed: "the current Chancellor is a woman who grew up in the East (though she was born in Hamburg), the Minister for Foreign Affairs is homosexual, the government includes a handicapped person and an immigrant etc." But on the other hand, they have remained the same: "none of the chiefs of staff are from the ex-GDR, there are no elite universities in the new (though after 20 years, you might say "not so new" ) Federal states, and not one of the country's first division football teams is located in the former East Germany. In short, Tagesspiegel argues that "Germany has all the trappings of freedom, but it is also more oppressed than ever." Worse still, "it is now devoid of self confidence to the point of indulging in hysteria -- and finally, it has lost the key quality, which made its reputation abroad - its zeal."

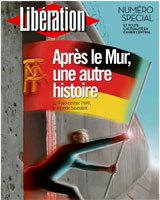

On the other side of the Rhine, the events of 1989 appear very far away. As Libération explains, the end of the division of Europe and the reunification of Germany are on the curriculum for final year students in French schools, but for most of them, the fall of the Berlin Wall "is part of another era - a positive but somewhat abstract event, which barely concerns them." In support of this observation, the daily also presents profiles of a number of young activists born in 1989, who are proud "to describe themselves as communists."

Further away from Germany, the memory of 9 November 1989 is even less important. As José Ignacio Torreblanca notes in El País, "the rest of the world is largely indifferent to the events that took place in the Berlin of 20 years ago." For the Spanish political analyst, "Europe is no longer the centre of the world. In reality, the vision of Europe as a pionneer of international change is illusory. With its two world wars, Europe put an end to its dominance years ago, and the world's centre of gravity has long been elsewhere." For proof that this is case, you need look no further than "the fall of the wall, a positive event (...), which had little to do with European leaders." Here Torreblanca emphasizes "the extraordinary shortsightness of Margaret Thatcher, François Mitterrand and Giulio Andreotti, who were plunged into a state of shock by the prospect of German reunification." Credit for the fall of the wall can only attributed "to the historic vision of George Bush Senior and Mikhaïl Gorbatchev." Twenty years later, "the EU has yet to exert a dominant influence in Europe, or any major clout in world politics." For these reasons, Torreblanca concludes that today's commemoration "should be a cause for concern," because it is now clear that "the fall of the wall and the end of the 50-year reign of the Iron Curtain did not prompt a European renaissance, but simply reconfirmed the decadent direction taken by the continent in 1945."

Could Europe's lack of political significance be behind

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!