This article is reserved for our subscribers

Oddly enough, the most visionary formulation of what we Europeans have tried to achieve on our own continent comes from an American president who deplored the “vision thing”. “Let Europe be whole and free,” declared George H. W. Bush in the German city of Mainz in May 1989 (1). He described “growing political freedom in the east, a Berlin without barriers, a cleaner environment, [and] a less militarised Europe” as “the foundation of our larger vision : a Europe that is free and at peace with itself.”

So the goal is threefold : whole, free, and at peace. How has Europe done against those benchmarks in the more than thirty years since 1989? Is the vision coming closer or receding? What would it take for Europe to advance further toward it ?

Europe’s Post-Wall Era

Europe’s post-Wall era is a tale of two halves. Painting with a broad brush, we can characterise the period from 1989 to 2007 as one of extraordinary progress. Political freedom spread across Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. Germany was united. Soviet troops withdrew. New democracies joined the European Union and NATO.

In 1989 what was then still called the European Community had just twelve members and NATO had sixteen. By 2007 the EU had twenty seven members and NATO twenty-six.

There had never been a time when so many European countries were sovereign, democratic, legally equal members of the same security, political, and economic communities. As a European citizen, you could fly from one end of the continent almost to the other without needing to show a passport. Many of the countries along the way shared a single currency, the euro. Here was an unprecedentedly large, single European space enjoying an unprecedented level of peace and freedom.

To be sure, this was also a period that saw five wars in the former Yugoslavia, including the most brutal, genocidal one in Bosnia. But the last of these wars, in Macedonia, was over by the end of 2001. These two decades also saw the 11 September attacks on the United States. Yet with hindsight 11 September, 2001, which was a major turning point in Middle Eastern and US history, does not appear to have been one in European history. The consequences of the US-led wars in Afghanistan and Iraq contributed to the radicalization of some of the Islamist terrorists who subsequently attacked European capitals such as London, Madrid, Paris, and Berlin, but the process of radicalization had deep roots in Europe itself, especially among second-generation European Muslims.

The crucial European turning point came in 2008. Two separate but almost simultaneous developments, Vladimir Putin’s military occupation of two large areas of Georgia, South Ossetia and Abkhazia, in August and the eruption of the global financial crisis with the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September began a downward turn that continued throughout the second half of the post-Wall period. The financial crisis segued into a “Great Recession” in many European countries. It also provoked the Eurozone crisis that started in 2010, hitting southern European countries such as Greece especially hard. Also in 2010 Viktor Orbán started demolishing democracy in Hungary. In 2014 Putin followed his Georgian aggression with the annexation of Crimea and the beginning, in eastern Ukraine, of the Russo-Ukrainian War.

The refugee crisis that began in 2015 prompted a sharp rise in support for hard-right nationalist-populist parties such as the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) in Germany and Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National in France. In Poland, the Law and Justice party, having won both the country’s presidency and an absolute majority in parliament, set about following Orbán’s example to erode Poland’s fragile democracy. In 2016 came the Brexit referendum, which resulted in Britain leaving the EU, and then the election of Donald Trump as US president, which was also a significant moment in European history. The Covid pandemic struck in 2020, with economic, social and psychological consequences that are still becoming apparent. This cascade of crises reached its lowest point (so far) with Putin’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022.

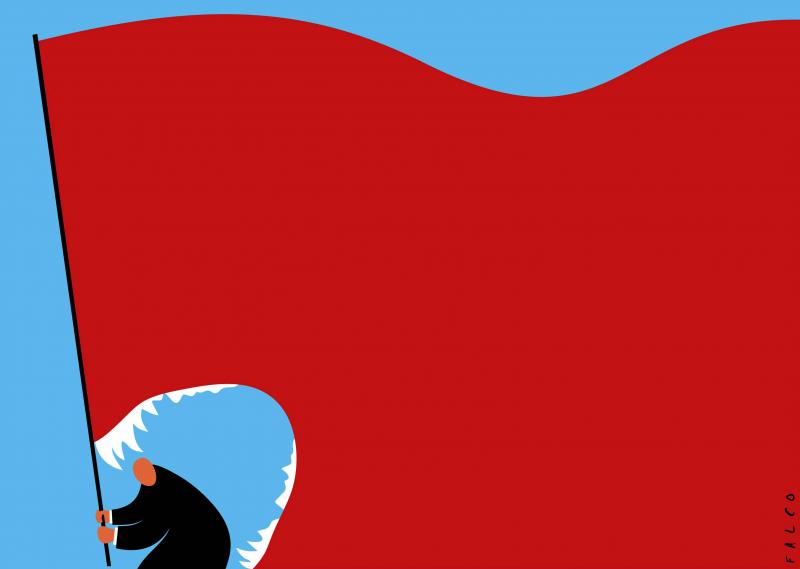

It would require another essay to analyse all the many varieties of hubris that contributed to this downward turn after 2008, but it’s worth highlighting one fundamental mistake in the way many Europeans (and Americans) came to view our recent history. Put most simply, this was the fallacy of extrapolation. We saw the way things had gone for nearly two decades after 1989 and somehow assumed they would continue in that direction, albeit with setbacks along the way. We took history with a small h, history as it really happens – always a product of the interaction between deep structures and processes, on the one hand, and contingency, conjuncture, collective will, and individual leadership on the other – and misconstrued it as History with a capital H, a Hegelian process of inevitable progress toward freedom. But freedom is not a process. It’s a constant struggle. The point is perfectly captured in the Ukrainian word volia, which means freedom but also the will to fight for it.

As the first half of the post-Wall period had not all been peace and progress, so the second half was not all conflict and regress. The European Union did not merely survive what one of its leaders dubbed its “polycrisis,” despite losing one member state (Britain) and another (Hungary) ceasing to be a democracy, in some respects it emerged stronger. Responding to the economic impact of the pandemic, the EU did what it should have done in response to the Eurozone crisis and launched a €750 billion financial support program called NextGenerationEU, which finally broke with two taboos that had been stubbornly up held by northern European creditor states such as Germany. It effectively mutualised some European debt, since the European Commission was authorised to borrow money on behalf of the entire EU, and it dispersed more than half that money as grants, not merely loans. The EU has also proved remarkably united and decisive in the face of the full-scale war in Ukraine.

Although it’s too soon to judge this last event in proper historical perspective, it seems plausible to suggest that February 24, 2022, marks the end of the post-Wall period that began on November 9, 1989. The scale and global implications of the war in Ukraine, and the way it compels Europeans to revise some of their most treasured post-1989 assumptions, mean that we have entered a new era, whose character and name no one yet knows. So where does Europe stand today? At peace? Free? Whole?

At Peace?

Europe is not at peace. In Ukraine we have the largest war in Europe since 1945. “Never again!” Europeans cried in 1945, after the horrors of World War II and the Holocaust. That was post war Europe’s first commandment. Yet southern Europe laboured under fascist dictatorships until the 1970s, while the eastern half of the continent continued to experience invasions and violent repression until 1989. After the end of the cold war, Europe settled down to be a continent of Kantian perpetual peace. Almost immediately, war erupted in the former Yugoslavia. Following the massacre in the Bosnian town of Srebrenica in 1995, Europeans again said, “Never again!” Now it has happened yet again. This is the “never” that seemingly never comes. When I started writing my book Homelands: A personal history of Europe, five years ago, I thought that in order to bring home to young Europeans the horrors against which post war Europe has defined itself, I must hurry to track down some of the last surviving elderly Europeans with personal memories of the hell that was Europe during World War II. So I did, in Germany, France, and Poland. But today all you need to do to experience such horrors firsthand is take a train into Ukraine from the southeastern Polish town of Przemyśl. Departure time 2023, arrival 1943.

In Bucha, the commuter town north west of Kyiv whose name has become synonymous with Russian atrocities in Ukraine, I met an elderly woman whose nephew had been murdered by the occupying Russian forces simply because he had some photos of destroyed Russian tanks on his phone. In Borodyanka I contemplated a statue of Ukraine’s great nineteenth century poet Taras Shevchenko, shot several times through his metal head by Russian soldiers. The intention of the Russian occupation is genocidal. Thousands of Ukrainian children have been separated from their parents and forcibly deported to Russia, where they are to be raised as Russians. In March 2023 the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Vladimir Putin, holding him directly responsible for this war crime.

I will never forget an evening conversation in Lviv with Yevhen Hulevych, a tall, lean, handsome cultural critic who had volunteered to serve in the Ukrainian army after the full-scale invasion. He had twice been wounded, the second time in the gruelling infantry campaign to liberate Kherson, but when I met him he was preparing to return to the front yet again. Inexperienced recruits would have need of him, he explained; his combat experience could save lives. A few weeks later he lost his own life to a Russian sniper’s bullet in the blood-soaked mud around Bakhmut, Ukraine’s Passchendaele (2). I often think of Yevhen.

Casualty figures in this war are difficult to establish, but in August US officials estimated that the total number killed and wounded was nearing 500,000: some 120,000 dead and 170,000–180,000 wounded on the Russian side; perhaps 70,000 dead and 100,000–120,000 wounded on the Ukrainian side. The number of war dead in this country of no more than 40 million people in just one and a half years thus already exceeds the US fatalities of 58,000 in nearly two decades of war in Vietnam. In a recent opinion poll, four out of every five Ukrainians said they know someone among their close family or friends who has been killed or injured. And there is no end in sight.

Is Europe itself at war ? Many people in Eastern Europe would say yes; most in Western Europe would say no. Europe is not at war in the way it was in 1943, when most European countries were direct parties to the conflict; but neither is Europe at peace in the way it was in 2003. Many European countries are supporting Ukraine’s war effort with weapons, ammunition, training, and money. And as in 1943, the only way forward to a lasting peace is through victory in war.

A cease-fire or peace agreement now, effectively compelling Ukraine to sacrifice territory the size of a small European country, would be a recipe for future conflict, not just in Europe but also in Asia, since President Xi Jin ping of China might reasonably conclude that armed aggression pays. Yesterday Crimea, tomorrow Taiwan. A nuclear-armed Russia cannot be reduced to “unconditional surrender,” like Germany in 1945. But an outcome in which Russia is forced to give up the Ukrainian territory it has secured by armed aggression is still attainable, and would be the only sure foundation for a durable peace.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!