Arian Leka in many ways is a peculiar phenomenon in the literary landscape of the Balkans and Europe as a whole. With his poems, short stories, essays and novels, he explores the idea of migration and exile in a thorough and coherent manner, with a particular focus on the Albanian experience, reflecting on the multiple relationships and turning points in Mediterranean culture and history.

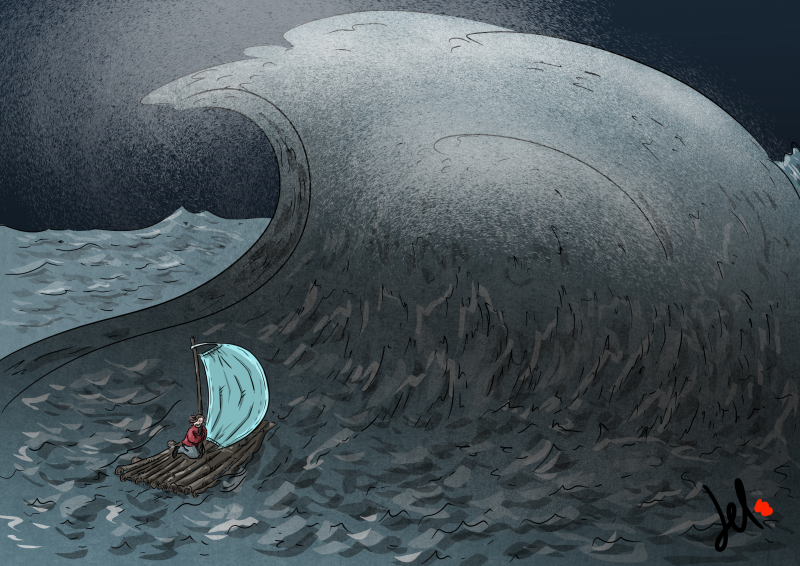

The sea is one of Leka’s literary obsessions: it runs through his works like a common thread, sometimes appearing as a space of hope, at others as a tomb for those who, in search of a better life, are swallowed up by its waters. In this conversation, Leka discusses the experience of Albanian emigration, literature in the age of artificial intelligence and the creative act as a perpetual and overwhelming game, with his hometown of Durrës in the background.

Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa: In Selected Poems, your latest book translated in the former Yugoslav space (Srebrno drvo & Treći Trg, Belgrade, 2023), you address issues of migration, displacement and exile, starting with the experience of Albanian emigration in the early 1990s. You then connect this experience to today's migration, where countless people, fleeing wars and other disasters, wander the world in search of happiness. Why is this theme so important to you?

Arian Leka: This edition is based on fragments of my larger work, Härte Memece për të mbyturit ["Mute Map for the Drowned", Poeteka, 2019], which explores complex literary themes through documentary chronicles, poetry and prose, between reality and fiction. In the book, moments from my life intertwine with broader experiences of the Albanian people and humanity as a whole, against a backdrop dominated by the sea. The idea of exodus exerts an immense force of attraction because it is not simply an escape or a departure that leaves open the possibility of return. It is a substantial displacement, an uprooting that transforms lives and landscapes, like a social earthquake.

For me, exodus is a physical movement and a universal constant, a metaphor for life. A journey. Birth itself is a small exodus, as is imagination. Throughout our lives, every day we experience small exoduses in school, social and working environments. Life is an endless succession of entrances and exits, a rite of passage. Even death is a form of exodus. These inner, more intimate departures prepare us for the final one. I see it as a perpetual big bang, a vast panorama of departures: leaving home, running away from love. In this context, the Albanian experience is a lens that allows me to approach the experience of other peoples connected to the sea, particularly the Mediterranean.

Historically, Albanians have been deeply affected by this force of expulsion, as demonstrated by the mass exodus. In the book, I used three registers to narrate emigration. It is not just the desperate who leave, but also citizens from wealthy social classes, taking with them pieces of their identity: columns, ornaments, jewelry, heraldic symbols, family crests, even flowers and animals – everything that can be transported, leaving behind only the trees, landscapes and tombs.

Although this is a book about migration, about those lost at sea, migrants and smugglers, in this work I also explore the infinite forms of exodus: running away from yourself while trying to preserve your roots and, at the same time, sowing the seeds of the Other. I am currently writing a prose about another exodus, that of the so-called “transitional man” in an era of transition which – paradoxically – is as long as the socialist one that preceded it.

From your books and essays it clearly emerges that emigration is one of the most traumatic experiences of post-socialist Albanian society. How has emigration influenced culture after the fall of Enver Hoxha’s regime?

I often hear people talking about the “Iron Curtain”, a concept that, however, implies the hope that the walls, sooner or later, will disappear or collapse. In Albania, there were no curtains, only concrete barriers and dead ends. Throughout history, there have been few exoduses like the Albanian one between 1990 and 1992, with ship thefts and the unprecedented attempts to convert any means of transport into boats. Even trucks with wheels were placed on barrels to transform them into boats.

The effects of that exodus are comparable to a tsunami caused by an earthquake. The direct consequences – shortages, isolation, linguistic and cultural detachment – continue to be felt even as the economic situation improves. Society remains divided. What began as a need to emigrate for work has transformed into a flight of educated and “accomplished” people in search of better opportunities, as if life could always be found elsewhere, far from their hometown.

’Throughout our lives, every day we experience small exoduses in school, social and working environments. Life is an endless succession of entrances and exits, a rite of passage. Even death is a form of exodus’

Like folktale characters, today’s youth pursue a hypothetical destiny, their “kismet”. This phenomenon now affects our entire region. There is the impression that our territories serve as primary suppliers of labor to Western countries that offer better living conditions. This is why this topic remains a fundamental part of my literary production.

As a man of letters, you are closely tied to the cultural landscape of the Mediterranean, which provides a backdrop for your books. What does your hometown of Durrës mean to you?

Writers often experience things similar to those of endemic and native plants. The place where I was born shaped my identity and instilled in me the belief that small spaces can be characterized by both local intimacy and cosmopolitanism. These spaces must be preserved, regardless of whether they were created by indigenous peoples or shaped by foreigners. The city of Durrës determined my understanding of the ephemeral and the imperfect. There is something peculiar about places where the sea is always present.

In Durrës, man stands face to face with the sea, yet they are two fundamentally different entities: the sea is vast and horizontal, while man stands upright like an exclamation point before the sea, an observer admiring the sea. This dynamic has profoundly influenced my imagination. Durrës has been the scene of numerous forms of social life, a provincial city but also a metropolis, both an ancient and experimental city, especially during the socialist period. A hidden corner of that typically Mediterranean peace and, at the same time, a place of rhythmic repetition: a propaganda exhibition, the seat of the first apostolic Christian community and the starting point of an atheist revolution.

We are talking about a paradoxical city, full of contradictions within its small yet fertile territory. A place where songs about landscapes, nostalgia and love abound, while those about courage are lacking. All these dynamics have shaped my writing intuitively and instinctively. My permanent home, my safe abode, is in my memories. Many intimate elements of my existence – walks, conversations, writing, swimming, music, love – originate in that city.

The sea is the fulcrum of your writing. However, it is not an exotic space dominated by sun and joy. I have the impression that for you the sea is an all-encompassing metaphor, a place where freedom and restriction, happiness and suffering intertwine. In one passage, you say that Mare nostrum has become Mare mortuum…

The sea, along with emigration, occupies a fundamental place in my writing. Variations on this theme appear in almost all my books, in various literary forms, particularly in The Ship of Dreams (2000) and The Book of the Sea (2009). I have consciously tried to avoid the clichés of Mediterranean postcards, choosing instead to narrate human destiny beyond the breathtaking landscapes – far from the sunsets and fragrant rosemary – and to explore the harsh reality of life by the sea. Sea-related jobs – those performed by sailors, fishermen, and so on – are anything but romantic.

I approached the sea through the prism of migrants, who appear on our screens only after tragedies. This erasure of migrants is a new form of ostracism, a modern racism. You speak of the sea as an “all-encompassing metaphor”, with its magnificent Mediterranean beauty and its dual nature as Mare nostrum and Mare mortuum. However, that Mare nostrum did not transform itself into Mare mortuum. We were the ones who transformed it into a monster that feeds on human beings. What is more, it seems to prefer swallowing ships whole. In my book Mute Map for the Drowned, I confront the images we often refuse to see: the dramatic and dark side of the sea.

‘Has there ever been an era marked by kindness and understanding?’

We tend to change the channel when tragic images appear on the screen, disturbing our comfort, arousing in us a profoundly human emotion – sadness – we often run away from. Faced with those images, we retreat to our modern caves – homes, offices and spas – where we “design” spaces of the “good life”, frame images of a serene sea and appear happy and smiling. It is easy, however, to be moralistic and constantly talk about the disappearance of human empathy. Has there ever been an era marked by kindness and understanding? Even in history textbooks, there is no such thing as a golden age. Prehistoric periods are named after weapons, tools and violent practices, think of the Iron and Bronze Ages.

Your books suggest that you deeply believe in the mission of literature, despite all the rapid changes and climate of fear that reigns in the world. What is the role of literature today?

Many proverbs hold that the pen is mightier than the sword and that what is written cannot be erased. I would like to believe it, but fencing is not my favorite sport. For me, it is a pipe dream, but I do not perceive it as desperation or a renunciation of my pen-sword. We must be realistic: writers are no longer those “mysterious creators of the world’s laws”. Today, rather than those ready to rebel, “priest-writers” prevail, as part of the literary procession and liturgies. It is therefore clear that the sword dictates the text, but the pen can still exert an influence on readers.

I come from a country that had lived under a dictatorship, where the pens of Albanian writers, unfortunately, had succumbed to the dictates of the ideological sword. Since political pluralism was banned, aesthetic pluralism was also lacking, unlike in the former Yugoslavia. The talented Albanian writers had turned their pens into swords, portraying socialism as a wonderful phenomenon that promised a rosy and secure future. I do not want to judge anyone, but it is easier to turn a pen into a sword than vice versa. We were not fortunate to have writers like [Miroslav] Krleža or [Danilo] Kiš, who lived in internal exile. Literature retains its meaning and power, but we must avoid creating a new utopia determined by writing.

For you, literature is also an infinite and perpetual game, a place without borders, a nomadic horizon that transcends every limitation and narrowing of the spiritual space. What does the creative process mean to you?

For me, writing implies, first of all, a “state of freedom”. However, writing does not always mean putting words on paper. The periods without writing do not worry me. I am still the same person, and the absence of writing does not diminish my being a writer. What defines me is what I have written, not what I intend to write. Sitting at my desk is a banal act. I feel like a writer not so much in front of my desk, in my chair, but in my workplace, at the “crime scene” to which I return. It does not matter whether I am writing, reading, looking at images, remembering, listening to music, staring absentmindedly at a wall, or delving into a topic. In all these situations, I prepare myself to write.

I am a nomad, constantly moving and reflecting. I do not have a specific workspace. My only “creative studio” was a cabin on the ship Iliria, where I worked for almost two years. That happened only once, thirty years ago. Today I write anywhere. I often work in quiet spaces in Tirana, between a bar and a library, set up as student workspaces. These places offer a climate of relative silence, like a concert hall where you can hear a cough, a whispered sentence, the occasional buzz. Sometimes I write in the car, more often on buses, sometimes while walking, I write in my mind, which then forgets more words than it remembers.

I take notes everywhere. Sometimes I take photographic notes that preserve traces of what I intend to develop in my writing. I have also been fortunate enough to have an entire city as my “studio”, sometimes Durrës, other times a literary residence. I have started some books in Sarajevo, only to leave them unfinished in China, Vienna, Pécs or Hong Kong. Before I begin work, I often surround myself with photographs and music, but not while I am writing. I am obsessed with images and sounds. Once published, I never return to my manuscripts. However, before publishing them, I read them aloud.

Sometimes my dear actor friends record fragments of my stories or poems. Listening to those recordings, I understand where I went wrong. I am very careful with language: I avoid archaic words and prefer contemporary vocabulary. I want my characters to speak naturally, allowing readers to understand who is speaking. I enjoy intertwining different literary genres and writing prose with poetic elements. I prefer to work around midnight, when one day ends to give birth to another: it is like turning the pages of a book.

I have written many pages about my hometown, focusing on the essentials and pointing out the aspects that connect Durrës to other cities. I have never glorified my city, perhaps to protect it, or to protect myself. Moments of demotivation outweigh those of motivation. As the proverb says: “The night is a ticking clock. The days end, not I”. I am not looking for so-called inspiration, but rather for stimulation and commitment, waiting to catch the crest of my wave and ride it. I have tried many times, often failing, but I know for sure that, sooner or later, I will emerge victorious.

🤝 This conversation has been produced within the Collaborative and Investigative Journalism Initiative (CIJI), a project co-funded by the European Commission. Originally published by Novosti and translated by Osservatorio Balcani Caucaso Transeuropa. Go to the project page

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!