In a world increasingly shaped by algorithms and corporate evangelists of artificial intelligence, the question of who controls technology has never been more urgent. In a conversation organised during the ZEG Amsterdam event, organised at the De Balie venue, journalist and academic Julie Posetti, data scientist Christopher Wylie, and journalist Natalia Antelava argue that the danger isn’t only that AI could malfunction – it’s that the people designing it already believe they are gods.

Posetti’s diagnosis is unsparing. The industry, she says, “bought into the lies […] of the men who told us that we had to move fast and break everything, basically, and that the casualties were just the byproduct of progress. We are occupying a world where we have total filter failure,” she reflects, recalling Clay Shirky’s line that “there’s no such thing as information overload, only filter failure.” Today, that overload “is both making us tune out, drowning out the truth, and somehow dividing us,” and “the polarisation that it delivers is really challenging, and I worry it’s insurmountable.”

That “filter failure” has only deepened with AI. Wylie – best known as the Cambridge Analytica whistleblower – warns that a technology capable of knowing, seeing, and predicting everything about us risks stripping away human autonomy. “If you imagine a future where everything around you is mediated by something that watches you and thinks about you, where it can see you at all times but you can’t see it, and it makes choices for you, how can you exercise your agency as an individual if the world is literally reacting and thinking about you?” The effect, he argues, is intrinsic as well as instrumental: a creeping infantilisation that “destroy[s] the essence of being a person.”

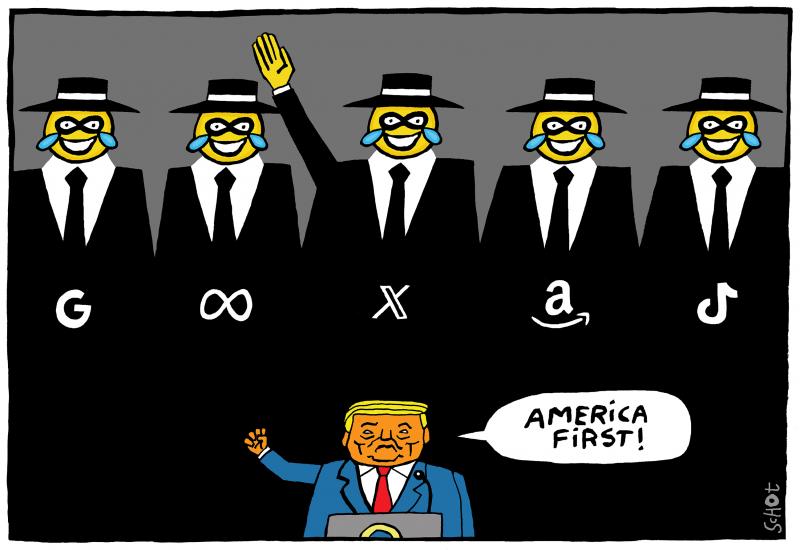

The cult of the tech messiahs

Wylie describes Silicon Valley as a “cult” – a term that might sound hyperbolic until you listen to its prophets. “They literally talk about creating God in their servers,” he says. “Elon Musk once said, ‘God might appear in my servers’. If you believe that, what does that make you? A creator. A messiah.” The haunting part, he suggests, is not only the grandiosity but the asymmetry between the power and knowledge of the programmers and those of the citizens.

For Wylie, the core problem is not eccentricity, but power. “I think people are starting to clock that there is an aspect of a cult being created in Silicon Valley,” he says – an ideology close to transhumanism, which posits that “you are creating the next evolution of humans that will not be strapped down with corporal or temporal mortality.” With billionaires “with taxis in the White House,” the risks scale from hubristic crusades “which kills a lot of people” to “some kind of apocalyptic event.” This techno-theological mindset, shared by “tech bros” such as Musk, OpenAI’s Sam Altman and Peter Thiel, fuels the belief that technology should transcend the limits of human life itself. “They see the next evolution of humanity as silicon,” he says. “Immortal, all-knowing, and beyond morality.”

Antelava, who co-produced a podcast on Silicon Valley’s ideology, recalls an anecdote that encapsulates the divide. “Chris [Wylie] once found himself at a party where people were talking about how to live forever – or at least how to survive when democracy collapses. And meanwhile, in another part of the world, journalists were meeting to talk about how to save democracy.”

Posetti argues that the media failed to treat these intentions at face value. Instead of covering them as a radical political project – “because this is effectively a doomsday cult, you know, on one level” – too many reporters found them “amusing” or “untenable.” These “tech bros”, as Posetti calls them, are now close to power – “aligned with lawmakers in the US, and effectively beyond accountability. Wylie adds that a “bizarre double standard” insulates tech’s most powerful: if a mainstream CEO proclaimed plans to “unemploy the majority of people,” or insisted that “God might be living in my computers,” they would likely be removed. For Silicon Valley’s titans, by contrast, “we then somehow just give them a free pass on saying crazy shit.”

The political illusion of neutrality

For decades, technology has been framed as neutral – an enabler rather than an ideology. Wylie dismantles that notion: “Building technology is an ideological act. Every aspect of the internet was designed with capitalism and Western individualism in mind. Algorithms don’t expand choice; they narrow it. They divide and monetise us.”

That logic, he argues, mirrors segregation and extends the metaphor to the physical world: “If you think about Facebook as a building,” it sorts people through different doors so they “all see completely different things.” Designed in concrete, “it would not be lawful. But we allow our entire digital architecture to use the logic of segregation in construction.”

The ideology embedded in digital design is, in Wylie’s view, a form of neo-colonialism. “Big tech is the new iteration of colonialism in the 21st century”, he says. “In the past, rich white men went to Africa or Asia to seize minerals or rubber. Now they come for data – our attention, our thoughts. And the impact is very similar, [...] undermining local governance and local people and leaving societies to deal with the wreckage.” He argues that the starting point must be resistance: not “how do we regulate their behavior,” but “how do we keep them out?”

Europe’s moment – and its limits

Against this backdrop, Antelava turns to the question of regulation. If governance is faltering in the United States, Europe, she notes, is one of the few places attempting to hold technology to account, through measures such as the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, the Digital Services Act, and taxation efforts. “Governments have woken up,” she says, “but is it too late?”

Posetti applauds parts of this agenda, particularly where the goal is to “ensure some degree of accountability” and enable “democratic deliberation in public spaces of the 21st century, which include digital spaces.” Yet she warns that “we’re playing catch-up,” that “we aren’t investing in the responses in the ways that are necessary,” and that some measures (for example, ID requirements for under-16s online) are “kind of counter-intuitive.”

The geopolitical headwinds are fierce. Progress on fair taxation and platform accountability, Posetti notes, has been “undercut and undermined by outright bullying from Trump in the tariff wars.” The imbalance of power is “beyond David and Goliath… you have this array of billionaires now aligned with lawmakers in the US” using economic and diplomatic leverage “to counteract the EU regulation.”

‘We do not have an internet right now that is designed to help you, that is designed to liberate you, that is designed to enhance your choices’ – Christopher Wylie

For regulation to matter, Wylie insists, it must be structural and enforceable. “There’s no safety regulator for tech. There’s no standards for tech.” We live, absurdly, with “more safety rules for a toaster in your kitchen than we do for a platform with a billion people.” The fix requires both design principles – which ideology should we use in engineering and design? – and accountability: coupleling that regulation with actual penalties, “which includes criminal liability for executives who contribute to things that are criminal”: “If Mark Zuckerberg was worried that the feds are going to come knocking on his door tomorrow, he would fix these problems.”

None of this, he stresses, is a problem that can be solved by a code alone. “The solution to political problems is always political, it’s not technological. We really are not talking about the elephant in the room, which is […] these are now political leaders in Silicon Valley, and they want to completely undermine our society.” In its current guise, he concludes, “I do not think that these companies should be allowed to exist in their current form.”

Reclaiming democracy

For all three speakers, the fight over AI is not about technology but about democracy itself – who gets to define truth, agency, and power in the 21st century.

Posetti argues for a renewed multilateralism – an update of the post-war settlement anchored in human rights. Given rising authoritarianism and “systems that are strangling truth,” she calls for “a kind of new approach to an intergovernmental solution,” asking “what kind of network response, regulatory network response, can we get beyond what the EU is trying to do.” She calls for a new intergovernmental effort akin to the post-war creation of the United Nations and the Council of Europe. “Those institutions were born from catastrophe — to ensure democracy, rule of law, and human rights,” she says. “We need to rebuild something similar for the digital age, because national regulation alone is failing.”

Wylie, for his part, invites a redesign from first principles – what he calls, provocatively, a feminist internet. “We do not have an internet right now that is designed to help you, that is designed to liberate you, that is designed to enhance your choices,” he says. Today’s dominant methods “separate you from others […] That’s not about community building.” Reimagining the stack means centring vulnerable users, power dynamics and abuse – engineering with social purpose, not just commercial optimisation.

Above all, he rejects the trade-off that has normalised harm: “The price of convenience doesn’t need to be human rights. These are not mutually exclusive things.” That should be Europe’s line in the sand. Rather than being a mere piece of paper, regulation must be a constitutional reset for the digital public sphere – clear duties of care, professional standards for software engineers, audited safety baselines before deployment, and criminal liability when platforms contribute to serious harm.

Europe, for now, stands as the testing ground. The AI Act, though imperfect, asserts a principle that Silicon Valley has long denied: that technology must serve people, not the other way round. Whether that principle can withstand the might of the new digital oligarchs will shape not only the future of AI, but the future of democracy itself.

Where is Europe standing?

In recent years, the European Union has established a comprehensive digital regulatory framework comprising the Digital Markets Act (DMA), the Digital Services Act (DSA) and the Artificial Intelligence Act (AI Act), in response to the threat posed by Silicon Valley to reshape the continent's institutions, politics and behaviours.

The DMA designates six “gatekeepers” (Alphabet/Google, Amazon, Apple, ByteDance/TikTok, Meta/Facebook/Instagram/WhatsApp, and Microsoft) and imposes obligations to prevent self-preferencing and anti-competitive bundling. In April 2025, the European Commission found Apple and Meta in breach of DMA duties relating to device steering and app store tying. In March 2024, the Commission launched non-compliance proceedings against Alphabet, Apple and Meta.

Why do these cases matter? DMA obligations relating to interoperability, limits on data use and anti-steering directly affect how gatekeepers can integrate AI assistants, bundle models in operating systems and use user-tracking data for training purposes (AI specification proceedings). The relevance of the Commission’s decisions is endorsed by BEUC, the key European consumer protection organisation, which welcomed the April 2025 rulings as “necessary to give consumers more choice”.

Conversely, the Digital Services Act now applies in full to very large online platforms (VLOPs, as defined by the Commission), obliging them to assess and mitigate systemic risks, such as algorithmic disinformation and AI-driven recommender systems. In March 2024, the Commission issued election-risk mitigation guidelines and integrated the Code of Practice on Disinformation into the DSA toolbox, which was published in February 2025. Ongoing DSA legal proceedings against X and TikTok are testing the algorithmic-risk provisions.

Furthermore, in January 2025, the Commission’s Vice-President Henna Virkkunen stressed that “algorithmic accountability and bias controls are central to the DSA enforcement agenda”. In line with the Commissioner, the digital rights coalition EDRi warns against “simplification and deregulation narratives” that could weaken the EU rulebook.

The AI Act (also known as Regulation EU 2024/1689) came into force in August 2024. It sets three distinct deadlines for firms using AI to comply: first, unacceptable-risk practices are banned from February 2025; secondly, General-Purpose AI (GPAI) model duties apply from August 2025; and thirdly, the EU AI regulations concerning high-risk systems will be phased in by the end of 2026 or beginning of 2027.

Much will depend on the work of the EU’s recently formed European AI Board, consisting of representatives from member states' enforcement authorities and a Brussels-based AI Office. The latter coordinates national authorities and oversees GPAI compliance. The office also advocates for member states' actions and policies to reap the societal and economic benefits of AI across the EU on a rolling basis, and shares best practices. It offers sandbox environments, real-world testing and other European support structures to encourage the uptake of AI.

After consulting the European AI Board and conducting a public consultation at the end of 2024, the European Commission published its General Purpose AI code of practice for companies and authorities. This code of practice will be regularly updated.

A continent locked in dependency?

Will this be enough to protect European citizens, businesses and institutions from abuse? “Implementation delays, weak consultations and undue industry influence threaten to render the AI Act ineffective”, warns the EU-wide digital privacy watchdog EDRi. Another key digital rights organisation, Access Now, has urged the Commission to “keep guidance human rights-centric and avoid industry capture”.

At the other end of the lobbying spectrum, the largest digital companies are lobbying heavily at a European level to influence GPAI codes and transparency rules. This is made easier by the fact that Europe's AI ecosystem is still overwhelmingly dependent on foreign technology, leaving the EU with little control over the model or hardware layer of the emerging AI economy. Almost all frontier models used across the continent – ChatGPT (OpenAI), Gemini (Google), Llama (Meta) and Claude (Anthropic) – are developed and hosted by US-based companies. Their models are also trained using high-performance NVIDIA GPUs, which are fabricated by TSMC in Taiwan.

No wonder the European Court of Auditors (ECA) warned in its Special Report 12/2025 that the Union “remains far from achieving chip autonomy” and risks falling behind the US and Asia in terms of semiconductor self-sufficiency. Similarly, the European Parliament's report “Making Europe an AI Continent” (September 2025) emphasises the ongoing “foreign dependency for AI gigafactories” and the necessity of coordinated investment in computing infrastructure and skills.

In short, the model layer is American and the computing layer is Taiwanese. If Europe focuses on regulation rather than implementation, it risks remaining a regulatory power without technological sovereignty.

Growing tension with Washington

As the EU continues to push ahead with the DSA and the DMA, tensions between the transatlantic partners are growing. Donald Trump has threatened to impose new tariffs and take other retaliatory measures against countries that adopt “digital taxes” or introduce regulations that he claims discriminate against American tech giants. A leaked diplomatic cable from 4 August revealed that US embassies had been instructed to actively counter EU digital regulation. This prompted European lawmakers to denounce Washington’s campaign as a direct assault on the Union’s sovereignty.

Despite the pressure, Brussels remains firm. The European Commission has opened multiple DSA investigations, targeting X for its algorithms and transparency systems and identifying preliminary breaches by TikTok and Meta for denying data access to researchers and hindering the reporting of content. Under the DMA, Apple and Meta have already been fined €500 million and €200 million respectively.

Meanwhile, France and Germany are seeking to redefine the balance between regulation and competitiveness. Their joint Digital Sovereignty Summit in Berlin in November aims to promote a 'simplified' EU regulatory framework to boost innovation — an attempt to align Europe's digital autonomy with its economic ambitions while navigating growing political and commercial friction with Washington.

| AI use data in the EU (2022–2025) |

| Despite the policy push, the uptake of AI in Europe remains limited but is slowly increasing. According to Eurostat, just over 8% of enterprises in the EU-27 with ten or more employees used AI in 2023, rising to 13.5% in 2024 — an increase of 5.5 percentage points. Among large firms, adoption reached 41.2%, while SMEs hovered around 11–13%. At workforce level, the initial results of Eurofound's 2024 European Working Conditions Survey show that approximately 12% of European workers currently use generative AI tools in their daily work, with national variations ranging from below 5% to over 20%. Public opinion remains cautiously optimistic: a Eurobarometer survey conducted in February 2025 revealed that over 60% of Europeans view AI at work positively, with more than 70% believing it can enhance productivity. However, an overwhelming 84% emphasise the importance of carefully managing AI use to safeguard privacy and transparency. Together, these data paint a picture of a continent that is curious about AI, yet still hesitant, and whose digital economy continues to rely on a handful of global providers. |

🤝 This article was produced as part of the PULSE project, a European initiative to support cross-border journalistic collaborations, and in partnership with De Balie. György Folk (EUrologus/HVG, Hungary), Elena Sánchez Nicolás (EUobserver) and Ana Somavilla (El Confidencial, Spain) contributed to it.

📺 Watch the full conversation between Natalia Antelava, Julie Posetti and Christopher Wylie at De Balie.

📄 Have your say in European journalism! Join readers from across Europe who are helping us shape more connected, cross-border reporting on European affairs.

O

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!