Along Kosovo's R107 highway, in a landscape of car washes and marble shops that smell of vinegar, the future is in a cooperative that packages ajvar, a roasted red pepper pâté. This cannery is located in Krushë e Madhe, a farming village in western Kosovo, and was started by Fahrije Hoti and other widows like her, with the support of international organisations. With more than 140 war widows in a municipality of just 3,000 inhabitants, the place is known as “the village of war widows”.

Three women in black, one of them at the wheel, exit a vehicle a few metres from the factory. They explain that there are many widows in the village as well as in the neighbouring one. Between February 1998 and December 2000, more than 13,000 people were killed or went missing in Kosovo’s war, when the ethnic conflict between Serbs and Kosovar Albanians escalated in the final stage of Yugoslavia's disintegration. According to the Humanitarian Law Centre Kosovo, of these, more than 10,000 were Kosovar Albanians, about 2,000 were Serbs and the rest were Roma and Bosniaks.

Sexual violence was used on a massive scale as a weapon of war. What could have been done better for survivors and what lessons can be learnt when it comes to other conflicts?

Financial insecurity, trauma and prejudice

“We have been through so much, and I was left alone with seven orphans,” says Meradije Ramadani, who lives near Krushë e Madhe, in a trembling voice. “Then we were forced to flee because of the Serb occupation, which destroyed us, our houses and everything we had,” she exclaims. “Thank God Albania opened its doors to us,” she continues. "Then we came back.”

Twenty-six years have passed since Meradije Ramadani's husband was killed and twenty-five years since she returned to Kosovo: “When we came back, we found nothing standing. Everything had been razed to the ground, burnt, reduced to ashes. It was completely destroyed,” she recalls. She remembers that, in that first year, they slept in tents, under plastic sheeting, because they had no house. Despite this, she continued to take her daughters to school: “Both my husband and I always wanted them to study and to be somebody,” she says. Today she says she is proud: “I educated them, I got them married and I have seventeen grandchildren. And all seven children have jobs”.

On the night of 24 March 1999, NATO began a series of bombing raids targeting Serb forces. It was the first time the Alliance acted without a UN mandate and that German soldiers participated to one of its missions. The next day, in the afternoon of 25 March 1999, paramilitaries and the occupying Serb army entered Krushë e Madhe and took its men away in retaliation.

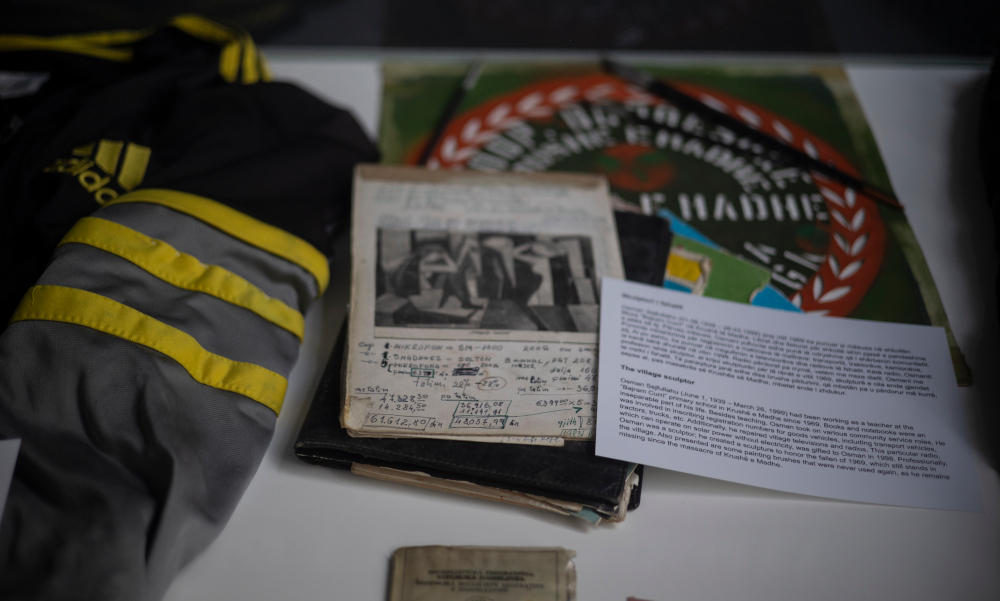

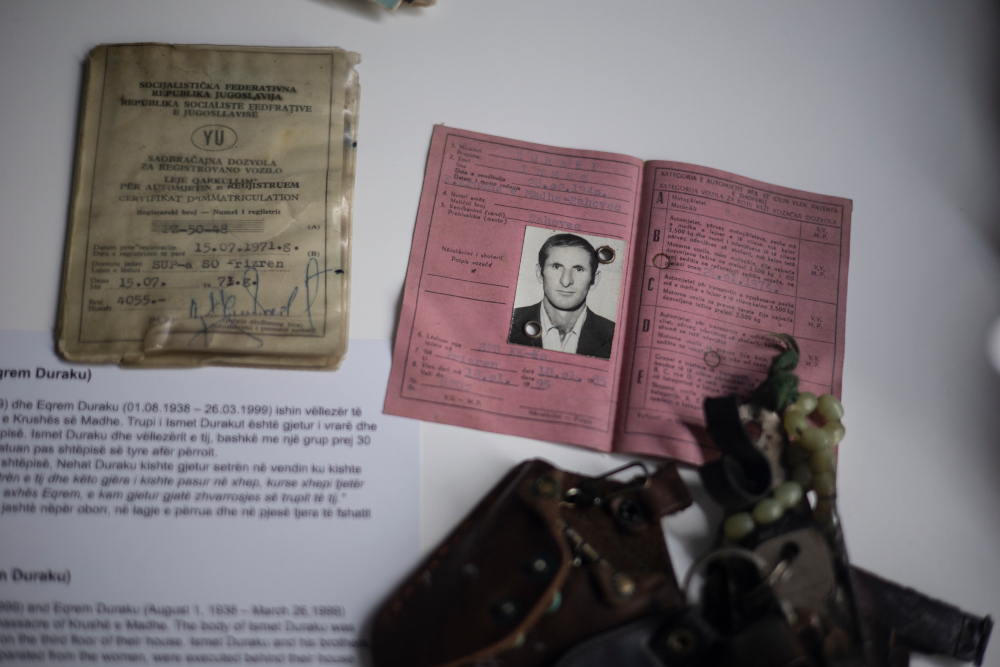

“Teacher, teacher, teacher...,” says Irfon Ramadani, pointing to the portraits displayed in Krushë e Madhe’s Massacre Museum one after the other. Ramadani was eight years old when the massacre took place: “They separated the women on one side and the men and boys on the other, and took them away,” he recalls, as he walks through the museum, where he is now a guide. In the display cases are exhibited the letters, clothes, glasses and books of his murdered neighbours. Among them, a backpack caked in mud. “Even in times of war, he never left his backpack or his books behind,” read a note written by the mother of a 17-year-old boy who wanted to become a doctor.

In the summer of 1999, Hoti returned to the ruined village alone with her two children, Sabina, aged three, and Drilon, a baby. There were many women in the same situation, facing a double-edged sword. On the one hand, they were mourning the death of their husbands, and on the other, they were facing social prejudice for taking on roles usually reserved for man. Hoti started selling ajvar and honey to neighbours, organising herself with other women. Today, her cooperative employs more than 60 widows and her story has been made into a film, Zgjoi (Hive). However, most of the women were unable to set up a business.

"Life was extremely hard, especially for the widows. They often spoke to me about the hypocrisy of the situation: on the one hand, they were put on a pedestal, celebrated as the widows of the martyrs, as the ones in charge of training the next generation. But at the same time, they received very little support", Professor Hanna Kienzler told El Confidencial. Kienzler is an anthropologist and co-director of the Economic and Social Research Council’s Centre for Society and Mental Health at King's College London. Between 2007 and 2009, she lived in Krushë e Madhe to research the effects of war on the mental health of female survivors. Since then, Kienzler has returned to the village every year except during the pandemic.

Kienzler says that, at the time, a widow's pension was 62 euros. "Do you know what you can buy in Kosovo with that amount? A bottle of cooking oil costs 2 euros and a pair of trousers costs the same as in Germany or anywhere else," she says. Widows had to use the pension to finance their children's education and often take care of other dependants. “This again created extreme stress,” she says. In 2014, the Kosovan government introduced a compensation scheme for different groups of people affected by the war, which was increased in 2025.

In addition to the financial insecurity and the trauma, there were social expectations: “They themselves or their children had to learn to drive the tractor, and once they had the harvest, women could not sell it at market themselves, because women simply did not sell things at market at that time,” Kienzler recalls. “Therefore, they often had to hire relatives or neighbours to sell their peppers,” she adds.

Most of them were unable to live independently either. Some women even had to give up their children. For Kosovar Albanians, as is the case with other groups in the Balkans and South Caucasus, the family is “patrilocal”: when a couple marries, the wife and husband are expected to move in with the husband’s parents and the children are considered to belong to the paternal family. This makes the system “organised along the male paternal line”, and sons are necessary to maintain the family line, as explained in a UN/World Vision report. As a consequence, some widows were forced to return to their parents' homes, leaving their children to be raised by their mothers-in-law and sisters-in-law. Flora, who lost her husband when she was 24, told Balkan Insight that she had been forced by her in-laws to return to her parents without her daughter, who grew up believing she was an aunt.

“If a woman was widowed and wanted to return to her parents' house, in most cases she was forced to leave the children behind, so many widows continued to live with their in-laws,” explains Kienzler. While widowers were expected to find a partner soon, it was still considered taboo for widows to remarry. In 2010, there were 5,052 war widows in Kosovo, of whom only 20 (0.4%) had lost their widow's pension because they had remarried.

Because of this, and because most did not have long-term financial support, very few managed to build their own businesses. “But this does not mean that they were not incredibly strong”, says the anthropologist, who becomes emotional during the video call. She gives the example of women like Ramadani who managed to put her six daughters through university, despite initially facing opposition from the village community.

“We need to speak out to end the stigma”

While they were battling social expectations on the outside, they were consumed by shame, suffering and memories on the inside. Talking about the trauma was not easy. In her research, Kienzler refers to it as the “symptom talk,” acknowledging that discussing these horrors can be so distressing that simply saying “I just remembered and now I have this headache or stomach ache” is enough. People understood what was being said because they had all experienced similar things.

Vasfije Krasniqi was 16 years old on 14 April 1999 when she was abducted by a Serbian police officer and taken to another village where she was tortured and raped by several men. She says it changed her life forever. Vasfije was one of the first people to publicly admit that she had suffered sexual violence during the war. “I want the world to understand that justice delayed is justice denied,” she told El Confidencial. Krasniqi warns that survivors of wartime sexual violence “need both immediate and long-term support, not decades of silence”, and emphasises that governments must act quickly to recognise victims, provide mental healthcare and bring perpetrators to justice. She believes that societies must change the way they view survivors: “We are not to be pitied or seen as symbols of shame. We are witnesses to history, and our courage can help prevent future atrocities. If my story teaches anything, it is that truth and dignity are powerful forms of justice, and that silence only protects the perpetrators, never the survivors.”

Almost two decades after the war ended, in February 2018, the Kosovar authorities established compensation of 230 euros for survivors of sexual violence. However, due to the stigma attached to identifying as a survivor of abuse, only 1,870 people had applied by 2023. It is estimated that around 20,000 women and men suffered sexual violence as a weapon of war.

Widows and overnight migrants

An estimated 200,000 ethnic Serb and Roma civilians fled Kosovo for Serbia in 1999, on the other side of the conflict. In August 1999, a Human Rights Watch report described the “wave of abductions and killings of Serbs” since mid-June of that year, including the massacre of 14 Serbian farmers, which was believed to be an act of revenge for atrocities committed by Serbian security forces prior to NATO's intervention. Many of those displaced were women.

"These women became widows overnight and had to flee immediately to Serbia in search of refuge for themselves and their families – their children, parents and other relatives. So, widowhood was accompanied by emigration to the country of their ethnic group, where, in many cases, they were not well received”, says Mirjana Bobić, a Serbian sociologist and co-author of the 2020 study On Widows and Social Injustice, in an interview with El Confidencial. Bobić explains that war widows and migrants took on the role of breadwinners, often working as vendors, cleaners, carpenters, café staff and bakers. Some were unwell.

“As the state was not very supportive, they mostly depended on family and friends who had fled with them,” she says. She says that the state was not accustomed to receiving so many refugees from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina in such a short time – the number was over 600,000, according to UNHCR data. Moreover, those who did not work could not count on Serbian state pensions before the age of 45. Their only income therefore came from allowances or funds given to their children based on proof that their fathers had died or disappeared in the war. 'This meant going back to the places they had fled, looking for bodily remains and presenting evidence.”

While the context may change, social, economic and psychological support mechanisms are essential in any post-war period to deal with both trauma and financial insecurity. In Ukraine alone, it is estimated that there are already tens of thousands of war widows.

👉 Original article in El Confidencial

🤝 This article was produced as part of the PULSE project, a European initiative supporting international journalistic collaboration. Nicole Corritore (Obct) contributed to its production

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!