“Turning to Europe” – that’s how French president Emmanuel Macron referred to the latest developments in Georgia, where tens of thousands gathered outside parliament to protest against – and successfully stop – the controversial “Foreign agents” bill. After a 3-day rally, the embattled parliamentary majority dropped the so-called “Russian Law” on second reading. The law was seen by many Georgians as an obstacle to their country’s democratic future, diverting the country from freedom and the “European path”. This is why the protesters, dominated by students, typically framed their protests as both a fight for Europe and for Freedom and Democracy in Georgia.

The proposed legislation was like very similar to the Russian “foreign agent” laws, with which the Kremlin has harassed and suppressed Russian civil society. Under the rejected Georgian bill, any legal entity acquiring more than 20 percent of its finances from a “foreign power” (a broad definition covering any legal entity not established under Georgian law) should be registered as an “agent of foreign influence”. Beyond the stigmatizing label, the bill granted government officials unfettered access to any legal entity, including its financial information, external correspondence, and the personal data of employees.

The bill also encouraged witch hunts – monitoring of any organization was permitted based on any written information referring to the alleged “foreign agent.” The bill included heavy fines as sanctions. The alternative bill registered by the sponsors of the original was even more limiting – extending from legal entities to individuals. It also proposed criminal sanctions, including imprisonment of five years.

Context: What makes it “Russian”?

Ever since regaining independence, Georgia has faced constant Russian obstructions on the road to democratic transition and the concomitant Euro-Atlantic integration. By August 2008, Russia’s imperial claims over post-Soviet, democracy-seeking regions was best illustrated by its aggressive invasion and occupation of Georgian territories. The fresh experience of fighting resurgent Russian imperialism hardened the pro-European sentiments of Georgians of all generations, especially those born in an independent country.

Despite Russia’s continued hybrid war against Georgia, and its increasingly obvious influence on the country’s governing majority, the Georgian public remains overwhelmingly in favor of European and NATO integration, with persistent public support of more than 70 percent. This highly trusting attitude towards Western institutions contrasts sharply with the governing regime’s propaganda efforts to undermine precisely those values that European integration stands upon.

At the beginning of 2022, after yet another Russian invasion of Ukraine, Georgia submitted its application for EU membership alongside Ukraine and Moldova. In June 2022 the European Council granted candidate status to Ukraine and Moldova, while it recommended a European perspective to Georgia, requiring the latter to fulfil specific conditions to attain candidate status. “Deoligarchization” – eliminating the outsized influence of oligarchs on social and political institutions – is among these conditions. The first person to come to mind in this context is Bidzina Ivanishvili, the former PM and founder of the ruling Georgian Dream party. Ivanishvili is often seen as the man who informally rules GD behind the scenes. Seeing the EU’s condition as an attack on his position, Ivanishvili responded with counterattacks.

The iconic words of the former Georgian PM, the late Zurab Zhvania remain firmly imprinted in the Georgian public imagination: “I am Georgian, and therefore I am European.”

However, it was not – or not exactly – Georgian Dream who initiated the bill in question. After a group of MPs left “Georgian Dream” to found an openly anti-Western, Russophile movement called “People's Power”, which ran smear campaigns against civil society organisations with the support of regime propaganda apparatuses, they initiated the “foreign agents” bill. Georgian Dream provided open support, while the authors attempted to pass it off as an American idea in order to endow the bill with an air of legitimacy and democracy.

Given the judicial system, geopolitical context, lack of independent judges, as well as constant delegitimizing campaigns against civil society organisations (CSOs) and media, it soon became clear to Georgian society that the bill would bring Georgia closer to Russia than to the west.

Restoring democratic hope

Georgia's civil resistance started with small and fragmented protests led by media and CSOs. Then an increasing number of international and local organisations joined the movement, along with many public figures. The rally peaked when the bill was adopted on first reading. The US Embassy referred to the bill’s adoption as a “dark day for Georgia’s democracy.” On March 7, tens of thousands gathered on streets and in digital spaces (#NoToRussianLaw) to oppose the “Russian law”. On both days, government forces attempted to forcefully disperse the peaceful rally with pepper spray, water cannons and batons, but civil resistance prevailed. Riot police detained 66 protesters, only to meet a larger, more powerful crowd the next day.

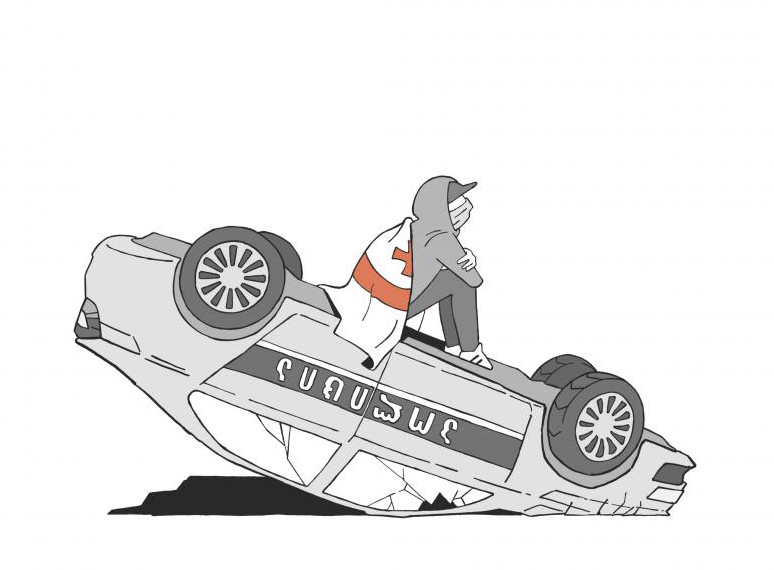

After a night of burnt police cars, broken windows and barricades in central Tbilisi, on the morning of 9 March, Georgian Dream issued a statement, assuring Georgians that they would "withdraw" the bill "until the situation calmed down" – shifting blame to the sinister forces that had allegedly spread disinformation about the bill.

Despite the statement, public distrust remained due to procedural delays in the planned withdrawal process. There was another rally that evening, urging the ruling party to schedule an extraordinary parliamentary session to vote down the bill at the second reading, since this was the only way to defeat a bill adopted on first reading.

On 10 March, at an extraordinary session, the parliamentary majority voted down the bill on a second reading. It is noteworthy that the Russia-friendly Georgian far-right has been the sole partner-in-crime for the Georgian government. Their small-scale, anti-EU and anti-liberal protest, held several days after the bill was rejected, was distinguished by violence and the burning of the parliament's EU flag.

Why does the world need to know?

This was a defiant victory for Georgian society, and a nuisance for the Kremlin. The fierce reactions from Putin's speakers, and the similarities with the Georgian government’s rhetoric, indicate that the draft law was not only a copycat of Russian law, but in fact a Kremlin-driven strategy. The rally was dominated by younger Georgians, who have never directly experienced living under totalitarian rule, or inhabiting an informational vacuum.

The iconic words of the former Georgian PM, the late Zurab Zhvania, marking Georgia’s accession to the Council of Europe, remain firmly imprinted in the Georgian public imagination: “I am Georgian, and therefore I am European.” Posters and interviews from the rallies show that this is a generation which cherishes freedom and democracy, and fearlessly opposes both Russia and the government’s targeted “politics of fear”. Even though this bill representing a major geopolitical choice was defeated, Georgia remains a country with many internal as well as external obstacles to the realisation of its “European future”.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!