Lea Vajsova is an assistant professor at the University of Sofia, specialising in sociology. She is interested in critical theory and social movements, and is a member of the leftist feminist collective LevFem.

Vladimir Mitev: How has the state of women's rights in Bulgaria developed over recent years? It seems to me that whatever happens in the USA has a significant impact on Bulgaria and who governs it.

Lea Vajsova: I tend to agree that American debates and political processes do have an impact on those in Europe and in Bulgaria in particular, but with some reservations. Global discourse is not only American, nor is the influence so unidirectional. During the tenure of former Republican president Donald Trump, various spokespersons for conservative organisations and/or conservative political identities in this country, which also look to the Republicans, certainly gained more self-confidence and for a short time were more present in our public space. In fact, it seems to me that this is one of their characteristics – assimilation of American Republican ideologies and those of the European far right. They behave as if the realities there and in Bulgaria were exactly the same.

We are witnessing a paradox: the nationalists claim that there is a cosmopolitan elite that is trying to destroy the nation state, while in reality it is the conservative spokesmen who are borrowing talking points, for example from the US, and imposing them in a local context.

In a sense, they are behaving like globalists. This is analysed in detail by the sociologist Mila Mineva. But of course Trump has not been the only factor.

Let us not forget that the crisis in Syria swept Europe with anti-immigrant sentiment. Unfortunately, this legitimised the far right, which gained a foothold in a number of European governments. For example, in 2016, the Bulgarian far right introduced the so-called "burqa law", with which it hoped to create public discord similar to that in France.

To explain how conservative voices become powerful enough to force a debate at one moment and then suddenly become marginal at the next, it is not enough to look at who is in the White House. We need to think in terms of which current global narratives are gaining momentum.

At different times, different issues come to the fore. For example, domestic violence seemed to be a bigger issue some time ago. Now it seems to be less talked about. But are there any societal issues that are coming to the fore?

To elaborate on your observation, I would like to start from the moment when the feminist collective LevFem was born, namely in 2018. This period was marked by debates on the ratification of the Council of Europe Convention on combating violence against women, the so-called Istanbul Convention. This document was ultimately rejected in Bulgaria as unconstitutional. The far right – at that time led by the United Patriots and the Bulgarian Socialist Party in the person of party leader Kornelia Ninova – launched a campaign against women and the LGBTQI+ community. It was this that provoked us to join the women's social movement.

In almost all the manifestos of the leading political parties there are policies aimed primarily at encouraging women to have children. This is clearly about white, middle-class, heterosexual women, who are expected to produce the disciplined workforce of the future. Fortunately, a more radical version of this conservatism, which might have included a ban on abortion, has not found its way to Bulgaria.

At the same time, however, the feminist movement of our recent post-socialist history had prioritised the problem of domestic violence. The activism of women's NGOs in Bulgaria, analysed by Maria Ivancheva, began with the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing in 1995. They initiated the Protection from Domestic Violence Act (PDVA). The 1990s saw the emergence of the concept of "women's rights" as well as "children's rights", conceptualised in terms of domestic violence and human trafficking. The general framework for work on these issues is provided by the concept of human rights. In the early 2000s, as a result of lobbying by women's NGOs, further laws were passed: the Child Protection Act (2000), the Anti-Human Trafficking Act (2003), and the Protection from Discrimination Act (2004). But in the end, it is the issue of domestic violence that has been the most significant for the feminist space in Bulgaria since 1989.

But we at LevFem were confronted with another problem in the women's movement: there were few clear voices speaking about socio-economic inequalities from a feminist perspective, or about the problems of being a woman and a caregiver.

It is a problem because, during the debate on the Istanbul Convention, we saw the conservative insistence on the "traditional Christian family" as a metaphor which obscured a process of re-traditionalisation resulting from the dismantling of the welfare state. The welfare state has played (and played before 1989 in socialist Bulgaria) an important role in achieving women's emancipation and equality.

For example, we have whole feminised industries that are absolutely crucial – health, education, social services, and the garment industry – and where labour is the lowest paid and working conditions are poor. It is no coincidence that the nurses' strikes have come out of these sectors. They are not only fighting for an increase in their wages, but also to criticise the subordination of healthcare to the logic of the market and to commodification.

There were protests by mothers with disabled children and by social workers. Such vocations became even more important during the Covid-19 pandemic, but the recognition of their importance seems not to have gone much further than applause from balconies.

Many women have chosen to emigrate, becoming nurses and domestic workers in Western European countries. We know that Bulgaria has traditionally supplied Western Europe with migrant care workers. On the other hand, it is not only the workers in these sectors who suffer from poor working conditions, devaluation of their jobs and low wages. They are also the citizens whose access to basic public goods is increasingly restricted. In Bulgaria, for example, we have a problem with a shortage of places in municipal nurseries and kindergartens in large cities, which absorb the internal migration flow. This affects women, who have to stay at home to look after their children.

‘There is a new wave of feminism in Bulgaria. Perhaps this is a positive thing, because there is obviously a growing sense that the public debate is regressing’

Our research shows that some women lose their jobs, others move to hourly work and more flexible work arrangements where their insurance coverage suffers, and others extend their maternity leave for the second year or go on unpaid leave for the third year. This means that their income falls and they become dependent on their partners and relatives. Again, women come out every year to protest about this issue, but mostly in vain, it seems.

Given all these trends, it is perhaps not surprising that many new organisations have emerged since 2018, including us. From a survey I conducted among them, it is clear that there is a new wave of feminism in Bulgaria. Perhaps this is a positive thing, because there is obviously a growing sense that the public debate is regressing and we need to think more purposefully about how to counter it.

What are the struggles of the women’s movement?

There are already serious efforts afoot to better understand the real situation of Bulgarian women. Indeed, this is one of the strands of women's activism in Bulgaria that is sure to go on developing. The nurses continue to protest and have received invaluable support in Dobrich from the leftist Varna collective Conflict. Stanimira Hadzhimitova's Centre for Sustainable Communities, in partnership with Italian colleagues, and Valentina Vasilonova of KNSB (Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Bulgaria), are together working on the issue of exploitation of female Bulgarian migrants in the Italian farm sector.

LevFem is also making systematic efforts to establish cooperation with trade unions. After the rejection of the Istanbul Convention, women's activism turned to lobbying for an amendment to the law against domestic violence. However, after years of effort, the new law was ultimately rejected in the National Assembly. In a sense, the law was held hostage to electoral politics, and now the organisations are back to square one. But the most disturbing statement was made in early 2023 by the coalition BSP for Bulgaria (BSP) at a congress: it committed itself to holding a referendum against "gender ideology in schools".

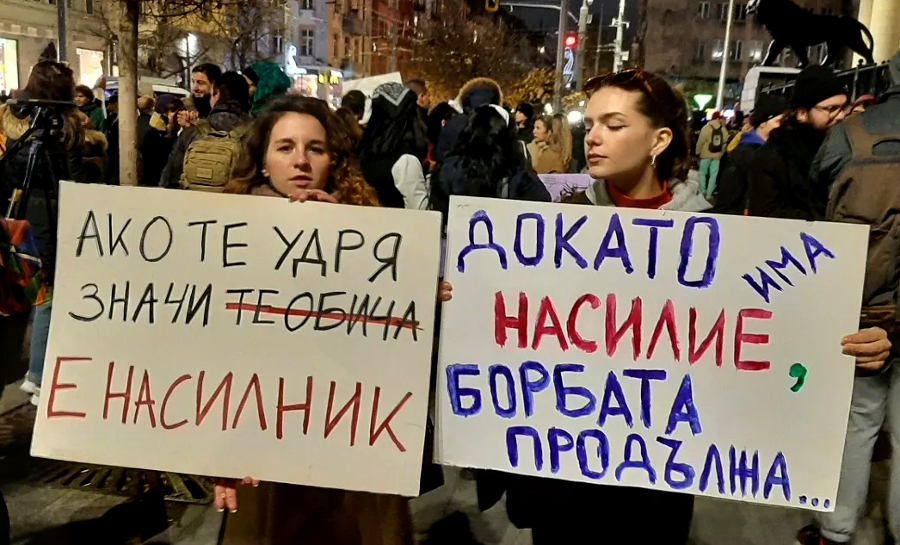

Since we are talking about political parties, it should be mentioned that women in political parties have also been marginalised following the Istanbul Convention. We are witnessing a serious decline in the representation of women in politics. There are also a number of new grassroots initiatives. For example, the feminist autonomous space Kopriva, which aims to create a place of safety and community, and the Feminist Library. The informal collective around Feminist Mobilisations, on the other hand, has dedicated itself to the 8 March and 25 November protests. These dates are significant in the fight for women's rights in Bulgaria.

Two years ago, there was a tragedy with a schoolgirl who was burned with acid. It was an extremely brutal crime. There followed a series of protests under the slogan "Ni una menos" – "Not one [woman] less". All over the world, organisations adopted this slogan during protests. In Bulgaria, another slogan was "You are not alone". Where are these movements going?

There is an informal activist group on Facebook called "You are not alone", where women who have experienced domestic violence can support each other. At the end of 2018, another woman was brutally murdered in Ruse. When news of her murder broke, there were protests in Sofia and elsewhere.

Discussions started about whether we should declare a Bulgarian #metoo movement, and thus add to the demonstrations planned for 25 November – the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women. But we did not want this movement to be a carbon copy of the American one. At the very least, if we called it that, there was a risk that journalists would impose a linguistic framework on us that had no relevance to what was happening in Bulgaria at the time. We decided to call it "You are not alone", and launched hashtags #НеСиСама and #NeSiSama ("You're not alone"), which quickly became popular and helped the protest on 25 November. Specifically, LevFem collected statements from women talking about the inequality they experienced, and published them. Interest was substantial. Thousands of people read them and shared them. In the end, we collected them all in a book.

But at that time I wouldn't say that we thought of this movement as international, even though we drew strength from the international context. We didn't have the strength to coordinate with other organisations from other places in a purely practical way. However, since the beginning of the pandemic, LevFem has been building a network called Essential Autonomous Struggles Transnational (EAST), which brings together trade unions, women's and LGBTQI+ informal activist collectives and organisations. Great efforts have been made in this direction by Kalina Drenska, Maria Ivancheva, Stoyo Tetevenski, Neli Konstantinova and Stoyanka Eneva.

For us, internationalism, especially in Eastern Europe and in post-socialist countries, is a very important line of work. On the one hand, there is no doubt that different countries have similar tendencies and it is important to work together with neighbours. On the other hand, as I mentioned earlier, a large part of the care labour market is supplied by women migrating from the East to the West, and it is important that we are part of the international women's social movement in which migrant domestic workers and carers have a major role.

The impetus for this movement within the European Union undoubtedly came from the former MEP and trade unionist Kostadinka Kuneva, and Convention 189 on domestic work is a particularly important document. Kuneva was also our special guest at the transnational meeting organised by LevFem in Sofia in September 2022, which was attended by over 150 activists from many countries.

Can you tell me a bit more about LGBTQI+ activism in Bulgaria?

The history of the LGBTQI+ movement before and after 1989 is just beginning to be written. But we can say that a pivotal moment was when the first Sofia Pride marched through the streets of Sofia in 2008 under the slogan "Me and my family". It was surrounded by police cordons and attacked with projectiles and Molotov cocktails.

The work of lawyers also stands out. To date, LGBTQI+ organisations continue to fight for an addition to Article 162 of the Penal Code on hate crimes committed on the basis of sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. They are calling for complaints and grievances to be filed when an incident occurs. The issue has become extremely topical due to the daily violence against the LGBTI+ community following the debate on the Istanbul Convention. These organisations also focus their efforts on the rights of same-sex couples, pushing for the legal recognition of same-sex cohabiting relationships. Lawyers are also taking up the cases of transgender people who want to be able to change the sex on their identity documents to match their gender identity. They are pushing for the alignment of Bulgarian legislation with that of the EU.

But what is specific to LGBTQI+ activism, as opposed to women's activism, is the sustained effort that goes into community building. A key role in this is played by the Rainbow Hub community centre, from which grassroots youth groups emerge. Such communities have also formed around the anarchist social centre Autonomy Factory/Fabrika Avtonomia. Another specific feature of young activists is that most of them define themselves as being on the "left" and think in an intersectional perspective, as opposed to those from the 1990s who had more liberal attitudes and an anti-communist identification. This difference has been analysed by sociologist Shaban Darakchi. The tendency for LGBTQI+ activism to be more grassroots-based than women's activism can also be seen as a consequence of the lack of a party committed to defending LGBTQI+ rights.

Finally, let's talk about the links between LGBTQI+ groups and feminist ones. What impresses you in this respect in Bulgaria?

Women's activism and LGBTQI+ activism have, for the most part, been parallel. A turning point in this respect was the debates around the Istanbul Convention, when women found themselves on the same terrain as LGBTQI+ activists. However, this situation is not typical of the Bulgarian scene, as some of the older feminists of the 1990s clearly distinguished themselves from LGBTQI+ activists and did not recognise the cause as their own. In fact, they claimed that it was harmful!

It is not clear whether and to what extent LGBTQI+ community representatives also see women's issues as their own. But it is only since the Istanbul Convention that there has been a greater need to look at intersectionality. Although there is a will to unite, we definitely need to consider the points of divergence and equivalence between what have historically been different forms of activism.

👉 Original article on Crossbordertalk. Read it also on LeaftEast

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!