At 5 AM on a chilly winter morning in 2022, a group of migrants were preparing an inflatable boat to cross the Evros River that forms the land border separating Turkey and Greece. After battling the strong current, they managed to reach EU soil and hide in the thick vegetation near the river bank – unaware that they had been under constant Greek surveillance long before they had even left Turkish soil.

Shortly after the group emerged from their hiding spot, they were ambushed by a special unit of the Greek police dispatched there after an alert from the Automated Border Surveillance System that Athens has installed and is continuously upgrading in the region.

Now covering much of the border described by European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen as Europe’s “shield”, this system can look deep into Turkish territory, boasting a range of up to 15 km, significantly enhancing pre-frontier surveillance for Greece and the EU.

The incident, detailed in a police record obtained during this investigation, illustrates Greece’s and Europe’s growing reliance on technology to secure their borders and curb irregular migration.

The arsenal at Europe’s disposal includes artificial intelligence (AI) systems, drones, thermal cameras, dialect detectors, data phone extraction and sophisticated surveillance networks. Depending on the country using them, the aim of deploying these advanced and often costly systems is to help prevent migrant arrivals, scrutinise asylum claims and disrupt smuggling networks.

Proponents argue that they are effective, provide safety and can be even life-saving, helping for example locate people in distress quicker than any border patrol ever could; critics counter that they are full of legal and moral pitfalls, undermining human rights, limiting access to asylum, infringing on migrants’ privacy, and can be used to facilitate collective expulsions – a practice that has been extensively documented and was recently described by the European Court of Human Rights as “systematic”.

Greece: a smart borders leader

As a frontline EU state bordering Turkey, the country hosting the world’s largest refugee population, Greece is spearheading Europe’s efforts to implement AI and other tech solutions in border control.

Greece has secured €1.6 billion from the EU’s Home Affairs funds for 2021-2027. Athens will invest heavily in border security and surveillance, including in AI-based systems, while a very small chunk of these funds is earmarked for improving search-and-rescue capacities, arguably reflecting where European priorities lie.

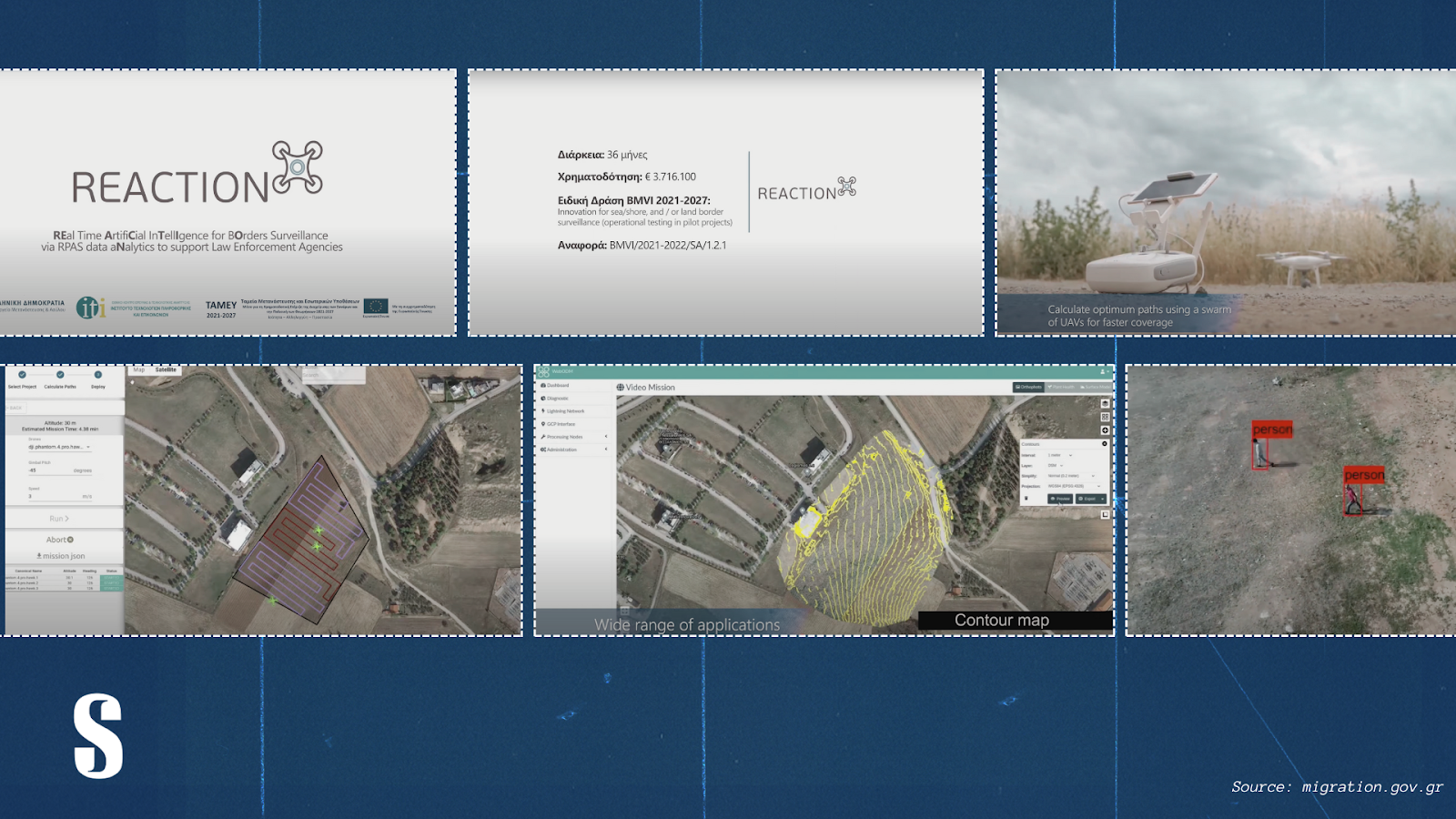

One flagship EU-funded project is called REACTION. AI-powered drones and vehicles will monitor borders in real-time, detect “threats” before they reach the border, and integrate with systems like EUROSUR, the EU’s border surveillance system. In a promotional video of the project, a swarm of drones can be seen autonomously identifying and tracking persons of interest.

Justifying the drive for border tech, a senior Greek government source said that “arrivals of more than 30,000 a year are challenging, so we have to focus on stopping criminal smugglers from pushing migrants into Greece any way we can.”

This informal target was dwarfed, however, in 2024, when more than 62,000 new migrant arrivals were recorded – double the limit considered tolerable by Athens, and 40% higher compared to the previous year. Government officials expect migratory pressures to continue in 2025.

This “aggravated period” for migration was the main reason Greece’s migration ministry declined to provide any answers or comments for this investigation on “sensitive operational issues that concern the security of the country.”

Sleepless watchers

In late 2024, at a gathering of law enforcement officials from across the bloc in Warsaw, where the EU’s border agency Frontex is headquartered, participants lauded Greece’s success in keeping migrant arrivals at the Evros land border under control. This success was largely attributed to the effective use of what participants called “technical barriers”, people familiar with the meetings recounted.

These barriers include a 5-meter-tall steel fence, already covering a substantial part of the 192-km land border with Turkey. The fence, which is planned to expand, likely with EU funding that had been previously denied to Athens, is augmented by a sophisticated array of technologies, including AI-equipped drones, ubiquitous cameras, and rapid-response teams.

Tech in the service of thwarting migrant arrivals was the focus of a detailed report published in late 2024 by BVMN, an independent network of NGOs that monitor human rights violations at external EU borders. The report describes Evros as a “technological testing ground” for Europe.

The borderline, along with the watchtowers and surveillance antennas dotting the Evros landscape, were recently mapped for the first time by the research group Forensis using satellite imagery, public tenders, and open source material.

Camera feeds are relayed to monitoring hubs near border towns, where officers sit behind wooden desks surrounded by screens, watching nearly every inch of the border and pre-frontier areas.

When drones or cameras detect activity, an alarm is triggered. Greek law enforcement will then often alert their Turkish counterparts, sharing coordinates based on shared maps, according to descriptions of the procedure by security officials. Turkish authorities often respond, while Greek patrols step in when they don’t.

This type of bilateral cooperation, which also includes regular in-person meetings between senior Greek and Turkish officials, was confirmed both by Greek and Turkish sources. According to official data, Turkey apprehended more than 225,000 migrants in 2024, with thousands picked up near the border with Greece.

Erosion of the right to asylum

Pre-frontier screening capabilities raise concerns. These systems not only make crossing the Evros harder, but can potentially prevent people in search of international protection from even coming close to the river.

Frontex’s Fundamental Rights Officer, Jonas Grimheden, for example, warned in an interview that while these technologies can make border management more efficient, they may also prevent people from exercising their right to seek asylum. This right is guaranteed both by Greek and EU law.

Greece is supposed to replicate the Evros model at its northern borders with North Macedonia and Albania, again with EU funding secured. A €48 million project under the EU’s 2021-2027 Migration and Home Affairs Fund envisions the installation of automated surveillance systems at these two borders.

This time, however, the goal will be to prevent migrants from moving along the Balkan route towards Western Europe, in what is known as “secondary movement”. Destination countries like Germany have been concerned about secondary migration, raising the issue time and again, including publicly and at the highest level.

Greece has been traditionally reluctant to apply the same level of vigilance at exit as in entry points, police officials said, a deliberate policy that has been well-documented.

A tech bonanza in the Aegean

In Greece, the more porous sea border with Turkey that accounted for most irregular border crossings in the EU last year, is also becoming increasingly reliant on tech to deter irregular crossings.

As in Evros, Greek authorities use radar systems and thermal cameras for the early detection of vessels before they leave Turkish waters. In a written response, the Hellenic Coast Guard explained that once suspicious vessels are detected, Greek authorities typically notify their Turkish counterparts asking them to prevent them from entering Greek territorial waters.

These advanced systems include long- and short-range radars that provide real-time data to patrol units, thermal imaging and high resolution optical cameras that allow the monitoring and detection of vessels 24/7, as well as unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drones equipped with high-definition cameras and tracking systems which provide aerial surveillance, especially over difficult to access areas and the open sea.

Tech at the sea border still plays, however, a comparatively minor role, according to a senior government official with direct knowledge of the situation, but the goal is for this to change soon. Currently no systems are based on AI, but the official said that Athens plans to improve this with new EU-funded systems and equipment.

The Coast Guard and police are indeed upgrading their capabilities with substantial EU funding. More than €25 million has been allocated for mobile surveillance technologies, including thermal cameras and heartbeat detectors, while €35.4 million is earmarked for electronic border surveillance systems. Investments also include unmanned helicopters, SUVs equipped with thermal cameras, and maritime surveillance tools.

On top of that, the Greek Defence Ministry has earmarked €21 million for the procurement of sea border surveillance systems, of which €4 million will be spent on the purchase of drones. With legal pathways to asylum still limited and preventive tech amplified, migrants are increasingly turning to well-armed smugglers using speedboats, prone to resorting to violence and dangerous manoeuvres to evade apprehension, making an already dangerous journey even more perilous.

The International Organization for Migration has recorded 173 dead and missing migrants in the Eastern Mediterranean in 2024, including 27 children.

As for those who do manage to reach the Greek islands, they often encounter another type of border tech: sophisticated surveillance systems.

Island panopticons

High security, drones, and AI systems have been hailed as innovative and essential features of the barb-wired, EU-funded camp in Samos.

These systems can track movement, identify individuals, and lock down sections of the camp with minimal human intervention. “The camp is designed to protect those outside, not inside it,” a person familiar with the camp’s operations said.

Several officials disputed this perspective.

“Protection of [privacy] is important, but security is also a grave issue. The new camps are unfairly criticised, they provide safety. There is no more violence,” a former senior migration official countered, juxtaposing the situation at the new camp in Samos to the “lawless situation” that preceded its opening.

Nevertheless, sources close to the asylum process suggested that the data collected could even influence asylum decisions, with behaviour flagged by the surveillance systems potentially used as grounds for rejection.

Asylum officers are independent according to Greek law, but periodically receive “guidelines” from central authorities, which leaves room to more ad hoc practices, the same sources said.

The Samos camp boasts two flagship surveillance systems, meant to serve as models for similar facilities across Greece: Hyperion and Centaur. The former controls entry and exit using biometrics, while the latter handles electronic and physical security in and around the facility using AI-powered motion analysis cameras and drones managed by the Migration Ministry.

Both systems have faced scrutiny. In April 2024, Greece’s Data Protection Authority (DPA) imposed a record fine of 175,000 euros on the Migration Ministry for “serious shortcomings” regarding compliance with GDPR rules.

Christos Kalloniatis, a professor at the University of the Aegean and a member of Hellenic DPA’s board, said the Ministry has since responded to the authority’s observations and the government’s responses are currently under review.

Kalloniatis warned that every system is susceptible to bias and it’s up to humans to eliminate such risks. “Bias exists if the people running these systems are depending only on them, rather than using them as tools that help them make a decision.”

He added that preventing and addressing violence is welcome, but it is a problem if asylum seekers, who find themselves in a situation of clear imbalance of power, are not adequately informed about their rights, what happens to their data, who has access to it and why, and do not give their informed consent.

Data privacy concerns

What is worrying Kalloniatis is already a reality on the ground. Migrants’ phones are often confiscated, passwords obtained, and personal data extracted. In some cases, specialised software is used; in others, officials simply photograph the contents on the screens of unlocked phones.

The Greek Police did not respond to requests for comment for this investigation.

The Hellenic Coast Guard said it can and does confiscate migrants' phones, but officers follow “strict legal procedures” under judicial supervision, and only as part of wider criminal investigations such as human trafficking or smuggling, as the phones could contain vital information about trafficking networks.

This is not always the case however. Three young Syrian asylum seekers interviewed in Samos said that their phones, as well as those of everyone they knew, had been seized by the authorities and returned later without explanation or any suspicion of them being involved in criminal activities. They were never told why their phones had been taken, did not sign any consent forms, and were not told when their devices might be returned.

Security sources confirmed that confiscations do occur regularly without judicial oversight or proper documentation.

The data extracted from phones is used not only in criminal proceedings, but also in risk assessments and reports by security agencies, such as the Greek police, Frontex and Interpol. “The data analysis is aimed at assisting authorities in identifying individuals, uncovering criminal networks, and ensuring public order and security”, the Coast Guard said.

We reviewed three reports based on extracted phone data. One, authored by Frontex, included information and pictures from social media and texts from messaging apps found on migrants’ phones to map smuggling networks. A second report, this time by the Greek police, included geolocation data, message exchanges with facilitators, and photos of tickets and itineraries. The third said migrants had offered their passwords “voluntarily”.

Greek law enforcement officials said that even private photos and other data are sometimes accessed. Even when migrants had them deleted from their physical devices, they are sometimes still accessible from the cloud.

Law enforcement officials also disclosed the informal sharing of information on migrants with counterparts from non-EU countries, bypassing the EU’s GDPR – touted as the toughest privacy and security law in the world – and other legal restrictions. This is done through informal channels like messaging apps between border guards who want to expedite the sharing of information, a process described as too time-consuming when proper channels are used.

*Names have been changed.

👉 Original article on Solomon

🤝 This investigation was supported by grants from the Investigative Journalism for Europe Fund, Journalismfund Europe and Netzwerk Recherche. This article is published within the Come Together collaborative project

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!