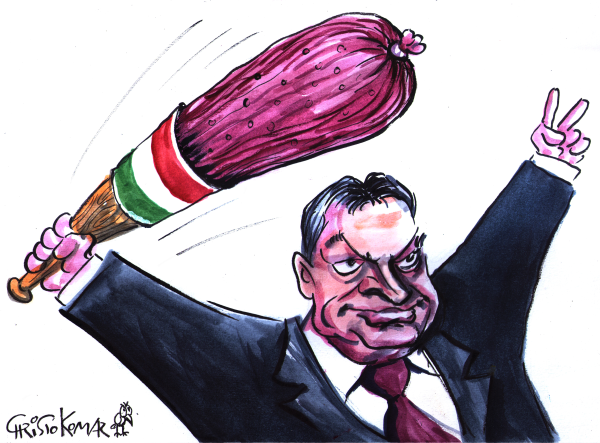

First step: build your media empire

The second government led by Viktor Orbán acceded to power in 2010, backed by a parliamentary supermajority. One of its first controversial moves was approving a series of amendments to the country’s media laws. These amendments included a law to set up the National Media and Infocommunications Authority (NMHH) and the Media Council. These would be responsible for overseeing the Hungarian media market, including media acquisitions. The Media Council, which was filled up with members loyal to the ruling Fidesz party, has been instrumental in aiding the expansion of pro-government oligarchs in the Hungarian media sector, who have slowly turned their outlets into government mouthpieces. The result of their expansion is the establishment of the Central European Press and Media Foundation (KESMA), encompassing around 500 government-influenced media outlets. Simultaneously, the state-owned media was taken over by Fidesz loyalists.

The Orbán government thus set up a Russia-like model of media centralisation, which has allowed manipulation of the population through centrally-controlled disinformation and a media empire that follows political orders. As a result of its efforts, the Hungarian ruling party has a massive number of media outlets under its direct or indirect control. This propaganda machine both follows instructions without question and can be directed against any (imagined) opponent of the ruling party.

Take a grain of information, turn it into an elephant

In August 2013, when Heti Válasz published its piece on the alleged actions of the so-called “Soros-network” in Hungary, the media-centralization process was nowhere near the stage it is at today. Yet it offered an early look at how home-grown disinformation campaigns would work in the future. After the initial article, several other pro-government outlets republished the original story or expanded upon it over the following months. According to these articles, George Soros was financing the Hungarian Civil Liberties Union, feminist organizations such as the Women for Women against Abuse (Nők a Nőkért az Erőszak Ellen), the Student Network, and independent media outlets like 444.hu and Magyar Narancs. Governmental figures such as Péter Hoppál, Fidesz’s spokesman at the time, joined the discussion, alleging that the Hungarian Helsinki Committee was a “pseudo-civil-society organization” discrediting the country and its government and financed by American money.

Heti Válasz’s article also claimed that the Norway Grants (funds designed to contribute to a more equal Europe and strengthen relations between Norway and 15 beneficiary countries) allocated to Hungary were being distributed to and by the same Soros network. According to the article, the board, which included Soros-protégées, decided on the fate of € 3.5 million in July-August 2013, a third of which landed at “organizations on the financing list of Open Society Foundations”. In April 2014, then-minister János Lázár wrote an official letter to the Norwegian government claiming that the Norway Grants in Hungary were managed by a civil-society organization, Ökotárs Foundation, with close links to a Hungarian political party, LMP (Hungary’s Green Party). Just a month later, the Government Audit Office notified Ökotárs about an investigation into their management of the funds. Meanwhile, Nándor Csepreghy, then a state secretary at the Ministry for the Prime Minister’s Office, accused some parts of civil society of being involved in “organized crime”.

He referred to an Ernst & Young (EY) audit report on the management of the Norway Grants in Hungary between 2008 and 2011. But soon after the accusations were made, the full report of EY was leaked online, showing that the firm had found the execution of the project to be “satisfactory,” and that it had not noticed systemic problems. On 8 September 2014, the police showed up at the offices of the Ökotárs Foundation and several others involved in the consortium managing the Norway Grants, including DemNet. The head of Ökotárs, Vera Móra, was taken into custody. According to the statement by the National Inspection Office, they were investigating allegations of embezzlement of funds and unauthorized financial activities. It turned out later that it was the prime minister himself who had given the order for the investigation.

No need to reinvent the wheel

These campaigns were built on widely-used methods of manipulation. In the case of the EY report on the management of Norway Grants between 2008 and 2011, Nándor Csepreghy misinterpreted the findings of the auditing firm. He did this by using information selectively so as to fit the ruling party’s worldview, by wildly exaggerating the problems pointed out by the firm while ignoring the general conclusion that the project’s management was satisfactory. The second important technique was making false connections between existing facts.

Interesting article?

It was made possible by Voxeurop’s community. High-quality reporting and translation comes at a cost. To continue producing independent journalism, we need your support.

The Open Society Foundation (OSF) publishes who it is funding online, so it hardly requires investigative journalism skills to reveal which organizations receive grants from them. However, Hungarian pro-government media treats all grants awarded in the form of money paid by the OSF to Hungarian civil society as forming part of a secretive plot. The government, as PM Viktor Orbán said himself, considers certain members of Hungarian civil society to be “foreign-funded political activists”, and government-influenced media relays this picture to its readers.

The most important goal of these efforts is to deconstruct any concept of “independence” in Hungarian society: all actors in the Hungarian public sphere must either be with “us” or “them”. Miklós Sükösd, an associate professor at the Department of Communication of the University of Copenhagen, added in Élet és Irodalom that, through these campaigns, the government also seeks to discourage critical voices from engaging in public discussion.

The third key feature of the campaigns is that the initial claim - the disinformation - is always much more viral than the truth that becomes apparent later. Péter Hoppál lost a lawsuit against the Helsinki Committee, a non-profit organisation devoted to human rights, for his statement concerning the organization’s alleged campaign against Hungary abroad. The police investigation into the management of the Norway Grants yielded no results. However, government-controlled media – predictably – does not inform its readers about these outcomes as loudly as they do about the original claims. The outcomes of lawsuits and investigations that cast the targets of disinformation campaigns in a positive light thus have little chance to influence public opinion.

In fact, government-influenced media outlets simply continue their campaigns after every lost libel lawsuit. Claims about NGOs have remained a constant presence in pro-government outlets, with regular allegations of hundreds of millions of forints going to “leftist-liberal civil society organizations” in order to “attack Hungary.” The Hungarian National Assembly approved an NGO law in 2017 – inspired by the Russian Act on Foreign Agents – that forced civil-society organizations receiving over 7.2 million forints (19923,18 euros)in funding from abroad to declare that they are ‘foreign-funded organizations’. The government is now planning to repeal the law, only to replace it with provisions allowing the National Audit Office, led by a former Fidesz MP, to audit NGOs with total assets worth over 20 million forints (55342,18 euros). The audit reports will likely provide a good opportunity for government-controlled media to continue discrediting Hungarian civil society.

Perfect the methods then use them all the time

It is not just NGOs that have been targeted by the Orbán government. Prime Minister Viktor Orbán remarked in October 2015, in a discussion at a conference entitled “The signs of the times”, that Europe was being betrayed in the migration crisis. It was an obvious allusion to George Soros. This off-hand claim was then turned into a years-long campaign to insinuate that the American philanthropist, civil-society organisations funded by him, and left-wing politicians and leftist media in general, are seeking to undermine EU countries via the creation of a multicultural society. In June 2018, the National Assembly approved the so-called ”Stop Soros” law, barring NGOs and others from “aiding illegal migration.” This campaign was partially invented by American campaign strategists.

In this context we can explain the large-scale campaign by government-influenced media outlets claiming that the opposition is following an anti-vaccination political strategy founded on recommendations allegedly made by political analysts – including the second author of this article. The pro-government media published more than 600 false stories to spread this lie, despite the fact that two first-instance courts found the allegation at the heart of the campaign to be untrue. More than a dozen government figures – including the prime minister himself – joined the campaign, showing yet again the centralised nature of these public attacks which aim to intimidate critical voices.

More effective than the Kremlin

Overall, the Hungarian government’s disinformation campaigns show remarkable similarities with those of foreign authoritarian actors, such as the Kremlin – in terms of media takeover, methods of operation and manipulative techniques used. The key factor of success for home-grown disinformation is the creation of a sufficiently large local media empire.

Direct Russian disinformation is not much present in Hungary, and it is clear why. Although RT, a Russian state-controlled television network, had wanted to open an office in Budapest, they later abandoned the idea, considering that the pro-government media was doing a good enough job.

There are three important reasons why locally-produced disinformation needs more attention and vigilance. First, disinformation campaigns can be much more effective when home-grown, since local authorities have more information on their own population’s preferences and needs (e.g. via internal public opinion polls). In fact, domestic manipulation efforts can increase polarization: since they are usually connected to one particular political force, they will have a stronger effect on one side than the other. As an example: while 27% of Hungarians say that NGOs in Hungary are the illicit mouthpieces of foreign interests, 49% of Fidesz voters do so.

As a result of years of pro-Russian and pro-Chinese coverage in government-influenced media, Fidesz voters have a higher opinion of these autocratic regimes than the opposition’s followers do. Second, national governments often have better reach compared to local pro-Kremlin portals, since they have the infrastructure and considerable public funds at their disposal. In Hungary, for example, the campaigns are run through the cabinet’s media empire. Third, domestic efforts focus their resources entirely in one country, while the Kremlin has to cover a much larger geographical area (even if there are more nuanced messages targeting single countries).

This all means that domestic, state-sponsored disinformation can be more effective in fuelling hatred, polarizing societies and channelling violence towards particular groups and individuals – mostly the symbolic variety, but not exclusively. It is time that the international community of experts and policy professionals dealing with this phenomenon start to address the issues of domestic, state-sponsored disinformation as seriously as they do the efforts of foreign authoritarian regimes. To imagine that EU member states are immune to the phenomenon is a dangerous illusion, and blindness to it could lead to the destruction of democracies in the heart of Europe.

In association with the Heinrich Böll Foundation – Paris