This article is reserved for our subscribers

In February, foreign ministers of the Weimar Triangle convened in Paris, in an attempt to give new energy to their trilateral cooperation. Comprising France, Germany, and Poland, the collective met just ahead of the second anniversary of the Ukraine invasion, to discuss, amongst other things, the challenges presented by escalating Russian assaults.

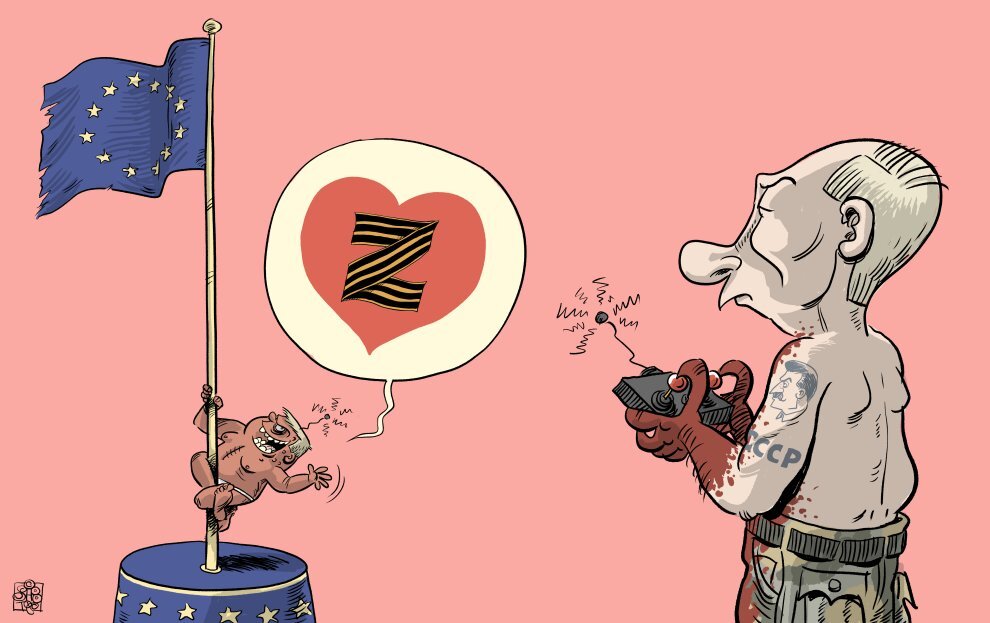

In an official declaration issued subsequent to the gathering, the German Federal Foreign Office asserted, "Russia is targeting us with hybrid actions, through disinformation, cyber attacks and political interference, with the aim to sow division in our democratic societies. This remains the most significant and direct threat to our security, peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area."

For several EU nations, the declaration came as little surprise, as the direct threat posed by Russia has been a palpable reality for decades. In Slovakia, Russian malign influence has arguably already left significant imprints on the country's democracy. Many attribute support from disinformation sources to the resurgence of former Prime Minister Robert Fico, a pro-Putin populist, who came to power last year. In Slovakia, experts have been scrutinising Russia's digital campaigns for years, resulting in a comprehensive understanding of how they operate. With the upcoming EU elections, it's crucial for member states to draw lessons from each other's experiences as they strive to uphold democratic integrity.

To wholly understand Slovakia's disinformation scene and its evolutionary trajectory, we must first address the conspiratorial tendencies of the Slovak population. Research by Bratislava-based think tank GLOBSEC uncovered that more than 50% of those polled in a cross-country study believed in conspiratorial narratives – making Slovakia the most conspiracy-prone country in the central European region.

Dominika Hajdu, Policy Director of the Center for Democracy and Resilience at GLOBSEC, described some of Slovakia’s most prevalent and influential conspiratorial narratives: “the conspiracy theories that have always dominated are those that claim democracies really don't exist because there are other ‘secret elites’”, she told me.

“Usually there is some sort of figure or entity, such as Bill Gates, George Soros, the World Health Organisation (WHO), or the World Economic Forum (WEF), who allegedly pulls the strings and decides what matters in Slovakia. The ‘secret elite’ is always somewhere there.” This belief that a faceless elite are actually in charge of Slovakia breaks down trust in democratic institutions, creating a “question everything” mentality when it comes to politics and society.

In recent years, theories regarding the war in Ukraine have held particular prominence, with research from GLOBSEC indicating that slightly over half of Slovaks believe that the West or Kyiv are responsible for the war in Ukraine, rather than Russia. Such beliefs are reinforced by disinformation sites, which pedal similar false narratives.

Communist-era nostalgia

In Slovakia, a huge proportion of the population continue to have pro-Russian attitudes. Many Slovaks are nostalgic about the communist era and they see Russia as a brotherly figure. Furthermore, the communist regime contributed to the conspiratorial thinking in the first place as during that time, distrust was everywhere.

In the era of the Iron Curtain, Slovakia experienced a period of relative prosperity. Industries flourished, and many individuals found themselves thriving for the first time. According to Hajdu, "the industry was inefficient because it was being propped up by the communist state," but for Slovak citizens, "at least they had jobs and their lives meant something." With the arrival of capitalism, these individuals found themselves sidelined, leading to discontent. Disinformation platforms capitalise on this sense of national nostalgia, amplifying pro-Russian narratives and reinforcing the notion of Russia as a "big brother."

‘The biggest challenge is for civil society to not give up’ – Peter Jančárik, Konspiratori.sk

Disinformation in Slovakia is spread in two main ways. Firstly, through political rhetoric, where politicians have long-exploited false narratives for their own political advantage. This tactic involves disseminating false information about both their adversaries and current events.

Many believe that Fico utilised conspiratorial tendencies and fake news to obtain success in the 2023 election. In an interview with France24, Alain Soubigou, a senior lecturer in contemporary Central European history at the Sorbonne, claimed that "Fico manipulates disinformation to such a degree that even the most intelligent, cultured and well-educated Slovaks find it hard to understand."

Secondly, disinformation is spread via online sites, which often pose as media organisations. Hajdu explained, “during the early 2010s, when Russia was in the process of annexing Crimea, we began to see different kinds of websites that were spreading pro-Kremlin propaganda. At that time the content was all about the migration crisis in the EU. They would spread lies about different minorities to instil fear into the Slovak population.”

Fluid disinformation websites

“Fast-forward to now, and we have this huge community of social media pages, groups and websites, that all support each other in the sense that they copy and paste articles from each other and spread disinformation.”

“The interesting and most effective part about disinformation websites, is that they’re very fluid” explains Peter Jančárik. “I half-jokingly say that Covid stopped existing when Russia invaded Ukraine, because all these outlets stopped caring about the pandemic and immediately switched to Russia-Ukraine disinformation. They can switch to any topic that matters to people that serve on polarising issues.”

Jančárik is a disinformation expert and co-founder of Konspirátori.sk, a platform which identifies fake news sites across Slovakia and the Czech Republic. The platform provides a list of all the disinformation sites they have identified, accompanied by a rating which is decided by a specialised review board. They have currently identified 315 such websites - with five to 10 reports coming in monthly. We like to call the platform the “Google Maps of the disinfo scene”, he summarised.

By identifying and assessing these sites, Konspiratori.sk equips both individuals and companies with insights into their lack of credibility, empowering them to make informed decisions. Individuals can choose whether to consume and place trust in the information disseminated by such sites. Similarly, companies can determine whether to permit advertising from these sources on their platforms: “we wanted to help companies become part of the solution and not the problem”, explained Jančárik.

Operating such a platform has not been without its challenges. Over the past five years, the Konspirátori.sk team have been awaiting a verdict on a case in which a specific site, identified by them as a distributor of disinformation, has filed suit against them on two separate grounds.

Free speech heralds

Sites promoting fake news often try to use free speech arguments in their defence. Jančárik noted, “it's funny that they always try to portray themselves as the ones bearing the flag of free speech, but when you start to speak freely about them, they immediately sue you and say that you are censoring them.”

He jokingly remarked, "we usually say to them, ‘you are free to say crap, and we are free to say that you are producing crap.’”

In 2022, Grigorij Mesežnikov, a political scientist and the President of the Institute for Public Affairs in Slovakia (IVO), wrote in an article for Visegrad Insight that “the Slovak disinformation scene as a whole has acted as the Kremlin's most devoted ally in all of Russia's activities and actions.”

Speaking on what he meant by this, Mesežnikov explained to me that in Slovakia “there is a very developed scene of Russian influence. All of them [fake news sites], are taking topics, narratives and stereotypes directly from Russia; with this agenda, they have the intention to change some systemic elements of our society.”

In conversations with several experts, it became evident that Russian disinformation has wielded and continues to wield a discernible impact on Slovak democracy. Hajdu highlighted that in certain instances, it's possible to trace particular sources back to Russian propaganda outlets, where articles are simply copied, pasted, and translated from Russian into Slovak.

What’s Russia’s goal?

Additionally, cases of bribery have surfaced. In March 2022, a video depicting a deputy military attaché from the Russian embassy bribing a contributor of one of the nation's largest disinformation sites sparked widespread outrage. Subsequently, the site was blocked. Russia's efforts at interference are unmistakable, yet it prompts the question: what is Russia's ultimate goal in all of this?

Peter Jančárik told me that, for Russia, “the endgame usually is to erode trust, so you don't believe anybody.” He went on to add that Russia knows that it cannot defeat the EU or NATO militarily or economically, but that it can weaken the societies that these organisations are comprised of. He added, “we've seen this with Brexit and we've seen this in the US, this is nothing really original.”

In recent years, we have repeatedly encountered accounts of Russia’s political interference. “Russia wants a ‘Slov-exit’. They were inspired by Brexit. After the collapse of communism, and creation of the European Union, the process was all about deepening and broadening integration – Brexit saw the opposite of this happen” explained Mesežnikov. He continued, the Kremlin’s goal is “to reverse the process of NATO enlargement.”

Michal Vašečka, sociologist and founder of the Center for the Research of Ethnicity and Culture, provided further insight into Russia's objectives. He elaborated that Russia's aim is “to systematically prepare the floor for the redistribution of cards in Europe. What happened in Europe back in 1918, was the collapse of the previous system and cards were distributed again.”

“For Russia the goal is very simple: to poison the European Union to the extent that it will collapse – a Union together is too powerful to deal with. The Kremlin wants to create lots of animosities between countries, so that the cards will be redistributed again. Then Russia has a chance to return as an imperial power,” he added.

While Fico adeptly leveraged disinformation sites for his political advantage in the months preceding the 2023 election, the very same Russian-influenced platforms consistently rallied behind him and his allies, belittling his opponents.

Similarly, for Slovakia’s presidential elections on 8th April 2024, it was reported that the campaign of Peter Pelligrini, one of Fico’s greatest allies and winner of the election, used similar tactics. In a recent report, The Center for European Policy Analysis (CEPA) noted that after the first-round success of Pellegrini’s opponent, the “political attack machine” supporting him “went into overdrive… using proxies and disinformation media outlets – of which Slovaks are unusually fond – to portray Pellegrini’s opponent as a “warmonger” hellbent on sending Slovak troops to fight in Ukraine”.

This symbiotic relationship between the two primary channels of disinformation dissemination in Slovakia has become increasingly apparent during the presidential and prime ministerial elections of the past year.

At the beginning of 2024, digital forensic experts in Germany uncovered an extensive pro-Russian campaign on X, which was using tens of thousands of fake accounts to spread disinformation about the current Scholz government. Analysts said they were convinced that Russia was behind the campaign, making a connection to the Russian-led Doppelgänger campaign that first emerged in 2022, affecting the UK, France and Italy.

Moreover, analysts noted a striking resemblance in the tone of responses to the counterfeit posts and the rhetoric employed by the Alternative für Deutschland (AfD) party. The AfD is deeply critical of several governmental policies, and these criticisms echoed throughout the disinformation campaign on X. Similar to Robert Fico and his Smer party, the AfD aligns itself with pro-Putin sentiments and has exhibited a sympathetic stance toward the Kremlin.

Efforts to address the issue of disinformation sites have been met with challenges. Dominika Hajdu described the situation as “very unfortunate”, noting the absence of laws enabling the government to block or suspend websites spreading false information. She emphasised that these sites not only propagate content aligned with Kremlin narratives but also meddle in internal politics. "I believe that blocking such Russian sites, which seek to undermine internal trust and interfere in domestic politics, should be a priority," she asserted.

This is where the EU could play a crucial role. With its sizeable market and influence, the EU can exert pressure on major social media platforms to implement reforms. There has been some progress, as evidenced by the recent implementation of the Digital Services Act introduced on 17th February 2024.

Next time the Weimar Triangle convenes, it may be wise for them to consider inviting representatives from EU member states, such as Slovakia, who have been faced with the threat of Russian disinformation campaigns for years. It is evident that there are numerous lessons to be drawn from the Slovak experience to fortify European democracy, particularly during this pivotal period.

When asked about Slovakia’s future hurdles, Jančárik said “the biggest challenge is for civil society to not give up.”

He furthered that “civil society will still need to find the motivation to show their value, to show what they stand for, to show that there are enough people who don't buy the stories. People who care about really improving the country”. Slovak democracy is under attack, “but at the same time, being under attack will motivate you to defend your role in society.”

Supported by Journalismfund Europe

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!