In a comparative analysis of mass protests, V-Dem (Varieties of Democracy) ranks “the pro-democratic mobilisation in Belarus in 2020 among the 15 largest and longest mobilisations among more than 100 countries in 50 years. Even the Ukrainian mobilisation of 2014 and the Venezuelan mobilisation of 2017 are lower in some parameters to the Belarusian one”.

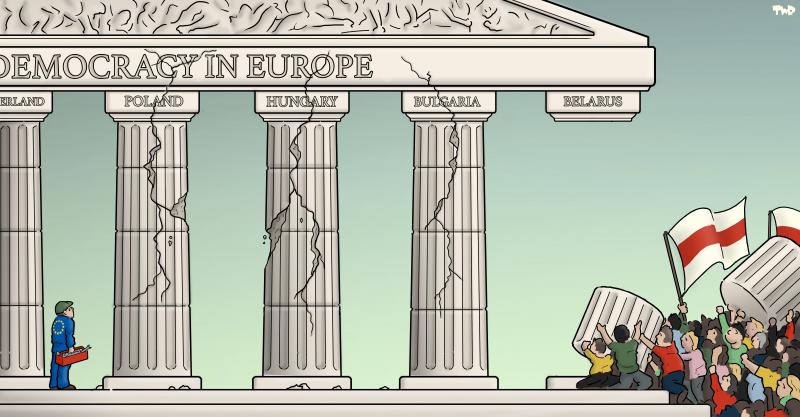

Belarusian society in 2020 demanded both an end to state violence and democratic reforms; however, the protests of that year did not bring about the desired result. Quite the reverse, in fact: the authoritarian regime has continued to strengthen its position. The methods used today by the state to tighten its hold on society bear traits typical of totalitarian regimes.

Even so, the suffocating atmosphere created by the political repressions does more than strengthen the feelings of insecurity, anxiety and fear among those who live in Belarus; it also demonstrates the fear of the regime itself, which continues to use unconcealed violence as virtually its only means of “interaction” with society.

Societies on a revolutionary course

“Is this a movement or a missed opportunity?” This is a question posed by Asef Bayat, a sociologist who has researched the Arab Spring, about the recent mass protests in Iran. This question links the 2022 protests in Iran with those in Belarus of two years earlier, as does the extent of public involvement in them.

In the first three months following the murder of the young woman Mahsa Amini by the Iranian police, two million Iranians – women as well as men – from all segments of society organised no fewer than 1,200 protest actions in over 160 towns and cities. Students of both tertiary institutions and secondary schools organised sit-in strikes; lawyers, preachers, professors, workers, sportsmen, doctors and artists publicly expressed support for the young people and joined the protests.

According to the leaked results of the sociological research conducted by the government of Iran in November 2020, 84% of Iranians viewed the protests positively. Participants in the protests – women formed one of the most prominent groups – were united by their pro-democracy demands. However, as is the case with Belarus, Iranian society is at present far removed from a “revolutionary situation”. Nevertheless, according to Bayat it is on a “revolutionary course”.

This means that a significant section of society continues to think, imagine, speak and act from the perspective of another, non-authoritarian future for their country. The reverse side of the coin is the conviction that sooner or later the ruling regime will collapse, that it is in fact doomed. “This is why any inconvenience – eg, a water shortage – is viewed as a failure of the regime, and any display of dissatisfaction – eg, because of a delay in paying wages – becomes a revolutionary act. It follows from this that the status quo is seen as a temporary phenomenon, and so changes are a matter of time.”, adds Asef Bayat.

He compares the point reached by the “revolutionary path” in today’s Iran with that attained by Polish society between 1981 and 1989, when martial law was introduced as a response to the unprecedented level of public activism that the independent trade union movement “Solidarity” had stirred up. “Solidarity” was registered in November 1980, and by March 1981 it had 10 million Poles as members. However, of no less importance for this public awakening was the fact that for the first time the workers were now joined by the intellectuals and the Church.

In the words of the Polish feminist theorist Ewa Majewska, the catalyst that brought about this public awakening was the opportunity to suddenly conceive a desire to participate in the country’s politics, to change them and to be involved in the process. The arrest in December 1981 of 3,000 of the most active participants of “Solidarity” and the total control of society established by the Polish regime led to the creation of an underground in the country in which women played a key role.

Shana Penn, author of an essay on the crucial role of women in the history of “Solidarity”, describes the underground in this way: “The underground became a frontier zone between private life and public life, between the past and the future, between tradition and democracy. It was the kind of intermediate space in which borders are erased, rules are weakened and changes occur.”