This article is reserved for our subscribers

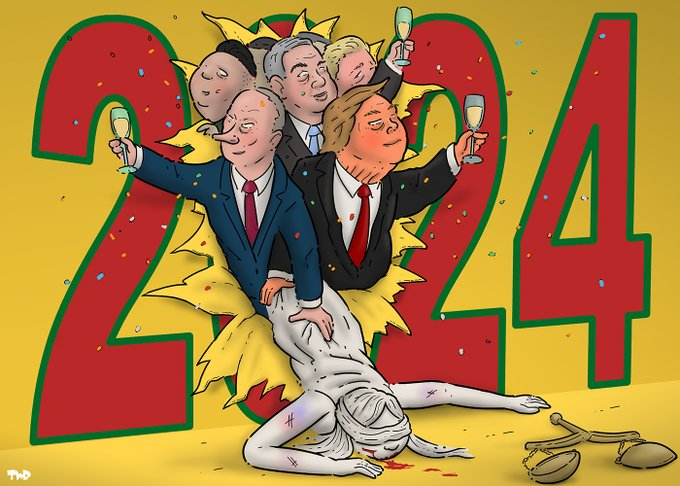

In the end, the Polish elections brought us just a short reprieve. For a few weeks, international media were celebrating how Poland had “shown how to beat populism” – “populism” is the favourite euphemism for far-right in centrist media. But Dutch politicians clearly hadn’t learned the lessons, as they created the perfect conditions for a massive electoral victory for Geert Wilders, just a month later. And so, after a short period of hope, we start yet another year in the shadow of the far-right, dominating headlines and setting the political agenda.

And yet, in many ways, 2023 was just another year in terms of European politics. The European Union (EU) was able to largely keep its pro-Ukrainian front together, mostly by giving dissenters exceptions to various measures (including sanctions), but has made itself even more irrelevant in the Middle East through its contradictory and disorganised responses to Israel’s brutal retaliations to Hamas’s gruesome initial attack.

At the surface, there were some (alleged) successes: Moldova and Ukraine were fast-tracked for membership, while a new €6 billion “growth plan” was passed to accelerate the halted accession of the Western Balkans.

Whatever the outcome, the EU will probably remain largely the same, i.e. divided over almost everything

In terms of national politics, there were no clear electoral or political trends visible in 2023, and most countries muddled through with different levels of success. The governments of both France and Germany continued to lose popular support, and face a growing electoral challenge from the far right, while most other big countries are also mostly inward-focused – the new Polish government will have a hard time de-PiSing the country, Giorgia Meloni is trying to hold her Italian coalition together as much of its economic program has been abandoned or softened, and Pedro Sánchez pulled of a masterful political comeback, but his new and fragile coalition will be haunted by the high price he paid for it, i.e. a highly controversial and unpopular amnesty deal.

In Hungary, EU thorn-in-the-side, Viktor Orbán, has become even more isolated this year. Having lost the vital veto of his Polish allies of Law and Justice (PiS), he will now be dependent upon either Meloni or the returned Slovak Prime Minister Robert Fico for protection from EU sanctions; but both have both less close contacts and less self-interest in bailing Hungary out. It will therefore be interesting to see how Orbán will use the EU Presidency, which is slated to move to Hungary for the second half of 2024. He could try to speed up the accession of the Western Balkans, which would add some of his allies to the EU, but will probably mainly leverage his (obstruction) power to release more EU funds and soften EU critique of his “authoritarian kleptocracy”.

So, the EU goes into this Super Election Year with its internal cohesion still intact, albeit increasingly patched up, and its international reputation at a new low. At the top of the electoral agenda, of course, are the European elections, to be held from 6 to 9 June in all 27 member states. With the far-right dominating the media and many polls, as well as the European People’s Party (EPP) having “veered right”, we can expect the European Parliament to become more explicitly right-wing – after the 2019 elections had already “moved the center” rightwards.

Although POLITICO’s Poll of Polls has shown little change in the seat distribution between the different political groups in the European Parliament in the past year, with only minor shifts compared to the 2019 results, these predictions have two shortcomings. First, a significant number of new parties will enter the European Parliament, which are not yet aligned with the existing groups (currently estimated at 41 out of a total of 710 seats).

Second, the number and content of the different groups can still change. For instance, there are rumors that the EPP was courting Meloni and her Brothers of Italy (FdI) party, while the electoral problems of French President Emmanuel Macron and his LREM party, as well as internal divisions over key issues and campaign strategy, raise doubts about the viability of the liberal Renew group.

But the most important group to watch is the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR), who are courted from two sides. Originally a conservative group, the ECR has been dominated by far-right parties, like PiS and FdI, for many years now. The main difference with the “real” far-right group, Identity & Democracy (I&D) of Marine Le Pen and Wilders, is their “reputational shield,” a leftover from its conservative origins.

But with most I&D parties electorally on the rise, their political exclusion is debated (e.g. in Belgium and even Germany) or outright broken (e.g. Austria and the Netherlands). One big “national…