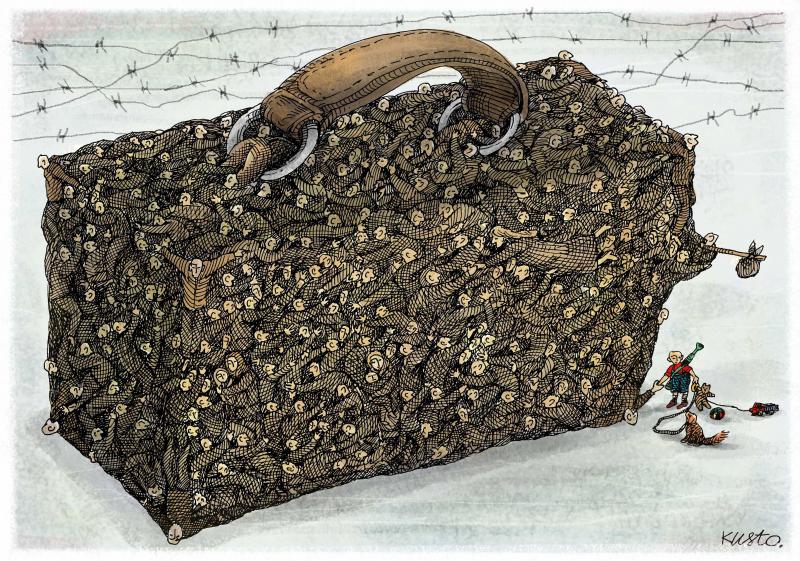

A few years ago, during an interview on the Pact on migration and asylum that the European Commission had just presented, the Italian lawyer Anna Brambilla said to me: "I propose to found the TGMAFL: Transnational Group of Mutual Aid for Frustrated Lawyers". Halfway between a joke and a call to action, the idea of Brambilla (who is a member of the Associazione per gli Studi Giuridici sull'Immigrazione, Asgi) was born of an observation: in a Europe that is increasingly hostile to exiled migrants, and faced with the ongoing dismantling of the right to asylum, defending the rights of migrants has become almost mission impossible. As a profession, it has been rendered almost meaningless by political attacks on so-called "militant lawyers".

The situation has not improved since 2020. A sense of powerlessness has grown among lawyers working on behalf of asylum seekers and others seeking to regularise their presence in the EU. European governments, of right and left, are working to restrict the rights of foreigners by changing laws or ignoring them, and trampling on fundamental rights in the process.

No practice is more emblematic in this respect than that of refoulements. While international law prohibits the return of asylum-seekers to places where their lives or freedom may be threatened, this has in fact become common practice in several member states, both at the EU's external borders (Bulgaria, Croatia, Spain, Greece, Hungary, the list goes on) and at internal ones (such as between France and Italy). Lithuania has just taken a major step by passing a law legalising the practice, but most of the countries that carry out refoulements at the border do so by knowingly breaking the law.

On Lesbos, a Greek island some ten kilometres off the Turkish coast, refoulements are happening "almost every day, sometimes several times a day, something the authorities systematically deny", says Ozan Mirkan Balpetek, advocacy and communications officer at the Legal Centre Lesvos (LCL), a Greek-registered non-profit organisation that provides free legal assistance to migrants.

Interesting article?

It was made possible by Voxeurop’s community. High-quality reporting and translation comes at a cost. To continue producing independent journalism, we need your support.

In Poland, lawyer Aleksandra Pulchny, a member of the Association for Legal Intervention in Warsaw, describes a similar situation: "Since August 2021, people who arrive from Belarus have been transferred by Polish border guards to the Białowieża Forest. This continues today because, despite the construction of the border wall, people still manage to enter Poland. And even though we obtain court orders, the border guards continue to turn them back."

To bolster its work in providing legal and humanitarian support to people arriving at the border, the association has created the Grupa Granica network with other partners. "We are also part of the Migration Consortium", explains Pulchny, "a network of Polish NGOs with which we publish common positions and hold meetings with the authorities". At the European level, the association has joined the PRAB project, which brings together organisations fighting against refoulements. "Joining forces with other partners is essential", says Pulchny.

Balpetek agrees, but stresses the importance of building alliances beyond the EU's borders. For example, on the seventh anniversary of the EU-Turkey cooperation agreement, LCL denounced it alongside 73 partners. "The fact that deaths occur in international waters or in 'no man's lands' means that lawyers working in the EU tend to work in collaboration with colleagues in neighbouring countries." Balpetek points to the ongoing cooperation in the case of Barış Büyüksu, a Turkish citizen who died on 22 October 2022, shortly after being found in a raft off the Turkish town of Bodrum. According to witnesses, he had arrived on the Greek island of Kos, where he was detained and tortured by local authorities before being deported with fourteen others. The autopsy report, recently published in Turkey, confirms the accusations of torture.

"The more the refoulements become a reality, the more we feel the need to collaborate with our colleagues in Turkey", says Balpetek. "Because mainland Greece is 500 km from Lesbos, while right now, as I speak, I can see Turkey from my window. Europe does not end in Greece or Bulgaria."

The three associations rely on strategic litigation, i.e. taking emblematic cases to a national or international courts in order to bring about wider legal and social change. "This can be useful, but there is a downside," Brambilla notes. "Because even when you win a case, the authorities get organised so as to thwart the outcome. We should not be discouraged by this, but perhaps we should rethink strategic litigation in order to better anticipate the possible reactions of the state."

Pulchny gives a concrete example. Following decisions of the European Court of Human Rights condemning the detention of illegally-staying minors, "some Polish courts changed their positions". Then, recently, the detention centre for families with children in Kętrzyn, in the north of Poland, was turned into a men-only facility. "We believe that this may be because the court that heard cases concerning this centre had become too 'pro-minor'," the lawyer explains. "Now families with children are being held in another city, where the court is not as sensitive, and we have to start our work again."

‘I often say that foreigners are a testing ground for repressive policy. This way of eroding fundamental rights is tried first on foreigners because nobody is interested in them. It is a very dangerous precedent’ – Selma Benkhelifa

"The state is annoyed that it has to submit to the law", says Belgian lawyer Selma Benkhelifa, a member of the Progress Lawyers Network. Benkhelifa is the type to have recited a Bertolt Brecht poem ("Our defeats, you see, / prove nothing, except / that we are too few / to fight against infamy") when a judge decided to send her client, an Afghan girl attending school in Belgium, back to her country of origin.

"It seems to me that when I started practising in 2001, judges and lawyers agreed on the basics: human rights are important, a black person and a white person are equal. But we were told 'Your client is lying', and we had to prove that he was not lying. For some years now, even when we show that the person could die if sent back to their country of origin, the judge replies: 'Too bad'." Benkhelifa and her colleagues have got into the habit of going to proceedings together "when we risk facing a very hostile court: to support each other, but also because sometimes you hear these things... And you wonder if you are dreaming."

More recently, in Belgium, even judges have been left in disbelief. Despite more than 8,000 convictions by the Labour Court and multiple injunctions from the European Court of Human Rights, the Belgian authorities continue to break the law by leaving thousands of asylum-seekers on the streets, even though all are entitled to accommodation. For Benkhelifa, this refusal to respect court decisions marks a turning point: "I often say that foreigners are a testing ground for repressive policy. This way of eroding fundamental rights is tried first on foreigners because nobody is interested in them. It is a very dangerous precedent."

Despite the scale of the challenges, from Warsaw to Brussels, from Lesbos to Milan, the determination to fight is unwavering. It is also a product of the mutual support networks that have arisen among these defenders of the rights of people on the move. "Of course there is frustration", Balpetek admits. "But what allows us to keep going is the enormous international solidarity." Such as that generated by the case of the "Moria 6", the six young Afghans sentenced, on the basis of dubious evidence, to heavy prison sentences for the burning of the Moria camp in Lesbos in 2020. (The appeal trial, which was due to start on 6 March 2023, has been postponed for a year.) "This solidarity is important for us, but also for the people detained." Across the EU and beyond, links between those who resist – lawyers, NGOs, activists – are thus being forged on a transnational scale.

Things are also moving within the legal profession. "I think that in the face of the current situation, some colleagues are becoming more radical", Benkhelifa remarks. "They recognise that we need to open the borders if we want to stop people dying." Brambilla speaks of the need to change course and perspective, not to think exclusively in terms of asylum but to return to original thinking on rights, freedom of movement and migration.

"The change must also be cultural and personal", she stresses. Thus, since 2022, Asgi has been offering its members meetings with migration specialists in fields other than law, so as to encourage a change of perspective and to avoid isolation and disciplinary fragmentation. "Moreover, it is clear that even among the 'experts', knowledge is still predominantly white and Western", adds Brambilla. "As Rachele Borghi, a lecturer in geography at the University of Paris-Sorbonne, says, there is a need to 'decolonise knowledge'", including in the field of law.

"I am clearly angry, but I am not in despair, because I believe that the question of human rights and democracy is an eternal struggle", concludes Benkhelifa. "The situation may get worse for a few more years, and then it will get better. When I wanted to become a lawyer, it was mainly out of admiration for the late French-Tunisian lawyer Gisèle Halimi. During the Algerian independence war, she pleaded for militants of the National Liberation Front who were sentenced to death. Halimi and her colleagues had the courage to do this because they believed in a free Algeria. I believe enough in the equality of all human beings and in the opening of borders to continue this fight. Even if, right now, it may seem utopian."