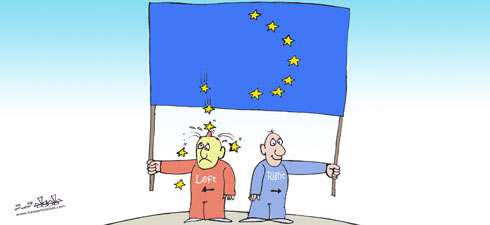

In some countries like Germany, France and Italy, centre-right and right-wing parties have been at the helm for several years. The situation is a little more complex in the United Kingdom, where the ruling Conservative Party has entered into a coalition with the liberal democrats, who could be described as centre-left. To complete this picture, we could add that centrist and right wing parties were also the winners of the most recent European elections.

The domination of the centre-right has not only been prompted by the weakness of the left. Much of its success can be attributed to strong and efficient political leaders like Nicolas Sarkozy, Angela Merkel and David Cameron who played a key role in election victories in France (2007), Germany (2009) and the UK (2010). The same can be said of the Spanish left, which benefited from the charisma of its leader Zapatero in its successful bid to retain power in Madrid.

Today, however, both Sarkozy and Merkel have run into difficulties. Sarkozy’s popularity has plummeted, and the fates have been less than kind to German Chancellor Angela Merkel, who until recently was celebrated as Ms. Europe, but now resembles a beleaguered Frau Germania struggling to rally support for her coalition government.

The immigrant question

In its quest to reconquer some of the territory it has lost in the EU, the European left should be able to take advantage of a number of factors including the economic crisis, which persists despite the relative resurgence of growth in some countries of the Union. But its chances of obtaining election victories over the right remain slim. Socialists and the social democrats have run short of coherent ideas to solve the problems that Europe now faces. At the same time, our contemporary developed societies are now beset by difficulties that could be described as "new types of crises," which are devoid of ideological colour.

The two most reported political stories of recent weeks — the deportation of Bulgarian and Romanian Roma from France and the publication of an anti-Islamic book by SPD member Thilo Sarrazin — appear to corroborate the general right-wing thesis which warns that Europe is unable to manage the problem of immigrants who, for the most part, are resistant to integration in Western society and are notably ungrateful to their host countries. At the same time, their presence is also viewed as a threat to national security.

According to this rhetoric, the lack of a sufficient commitment to the preservation of Europe’s cultural heritage has meant that Europe can no longer hold its own against Islam. For many commentators, the fact that this book has been penned by a social democrat is proof that left-wing ideas have run their course. Clearly it’s a far cry from the left’s traditional opposition to nationalism and racism, and the decades-old drive to construct a tolerant multicultural society.

At the same time, traditional left-wing recipes do not offer an effective remedy to other key problems in our societies. And this is particularly the case in the field of economics, where the left announced the end of the right-wing “neo-liberal” model, but consistently failed to propose a viable alternative.

Chavez and Lula - heroes of a weakened European left

In the domain of counter-terrorism legislation, the strictest measures have been introduced by left-wing governments in the UK, Germany and even more remarkably in Spain. And let’s not forget that it was a Labour government that brought the United Kingdom into the war in Iraq, which marked a clear shift from the traditional pacifist stance adopted by left-wing parties.

On a global level, the weakening of the European left has been accompanied by the rise to power of more aggressive left-wing politics typified by the Venezuelan model. For many intellectuals weary of capitalism, the main advantage of the ideology proposed by Hugo Chavez, which has been marked by a host of radical measures — including the nationalisation of private property and companies, state control of the media, and anti-Western and in particular anti-American rhetoric — is the fact that it has stopped short of introducing a Marxist-Leninist totalitarian system.

Venezuela is in a position to finance the export of its eccentric brand of socialism, because it is an ideology that has its basis in the modern economy. Another anti-capitalist champion, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, has also succeeded in promoting his own version of left-wing politics to ensure the prosperity and well-being of a majority of Brazilian citizens. The formula adopted by Lula, which is different to the one proposed by the traditional left, is mainly marked by the promotion of a strong economy that is adapted to the needs of the state. And it is not for nothing that anti-globalisation campaigners in Europe and North America are so enthusiastic about Lula but much less fanatical in their support for Chávez, or Spanish PM Zapatero, who has been forced to limit his left-wing programme to the traditional tussle with Catholicism and other conservative Spanish traditions.

Europe is now characterised by the ongoing blurring of the left-right divide, and political ideologies are increasingly seen as irrelevant. Class background is no longer important, and much less significant than nationality and regional identity. And that is why the road towards the resurgence of left-wing ideology in Europe will be long and full of potential pitfalls.

Analysis

European left-wing burnout

“The whole European left should storm Sweden,”urges Le Monde in an editorial. Sweden, the “cradle of modern social democracy and of the most successful welfare state of the past half century”, has been rocked by a “double political earthquake”: the far right’s entry into parliament and the Social Democrats’ abysmal score at the polls. In an effort to explain the decline of the European left, Le Monde spoke with Italian linguistRaffaele Simone, who attributes the “triumph of the right just about everywhere on the Old Continent” to the “intellectual exhaustion of the left”.

The left “doesn’t seem to have understood a thing about the sea change in civilisation wrought by the victory of individualism and consumption”, and until quite recently it “refused to discuss mass immigration and illegal immigrants”. Le Monde argues that the controlled immigration “needed to keep the welfare state going in our aging societies presupposes a huge integration effort that hasn’t been made”. But there may be a price to be paid for integration, the Parisian daily suggests: “Will the European-style welfare state survive by doing less in its traditional domains – health care, pensions – and more to tackle its new task: integrating immigrants?” For Le Monde, that is the crux of the message from Stockholm.

Was this article useful? If so we are delighted!

It is freely available because we believe that the right to free and independent information is essential for democracy. But this right is not guaranteed forever, and independence comes at a cost. We need your support in order to continue publishing independent, multilingual news for all Europeans.

Discover our subscription offers and their exclusive benefits and become a member of our community now!