This article is reserved for our subscribers

New EU-funded research projects to protect Europeans from potential future pandemics have just been approved by the European Commission (EC). But the road to strengthening the EU's resilience to cross-border health threats is still long and steep.

The fragmented and underfunded system built around the nascent Health Emergency Response Authority (HERA), part of the Health Union package, suggests that the EU has not learnt the two key lessons from the Covid crisis: long-term planning and greater investments.

The voices of scientists across Europe seem to have fallen on deaf ears once again, as they did before the tragedy. Yet another may be just around the corner.

“The World is not ready for the next pandemic, in case a new virus emerges it would take at least one year to have the first vaccines; broader-acting drugs should be developed,” prophesied Johan Neyts, professor of virology at the Belgian University of Leuven, at the 8th international Symposium on Modern Virology in September 2019 in Wuhan, China. A couple of months later, in the very city which hosted the event his forward-looking speech would sadly turn into the global havoc we have all experienced.

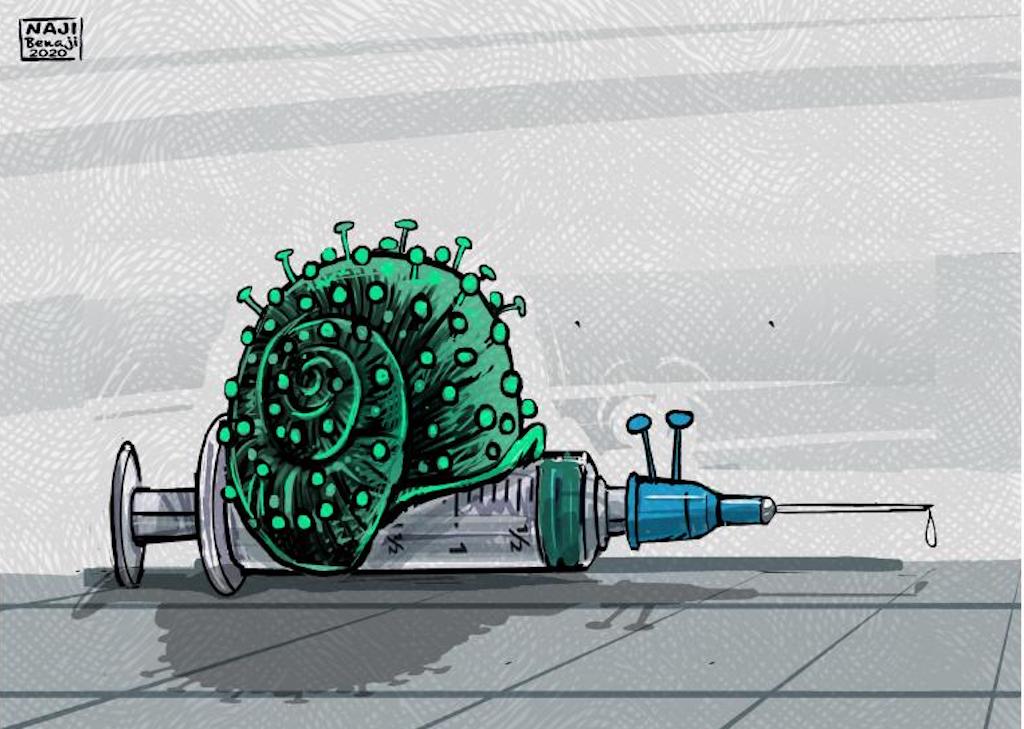

“If you have an enemy attacking you, then you’d better have your weapons ahead of the attack, so you need to build them in peacetime,” said Neyts “Instead, what we did with SARS-CoV-2 (the virus causing Covid-19) is that we waited for the attack and then we started building our weapons.”

That's it. The European Union (EU) has spent billions of euros fighting the Covid crisis, but only a few million trying to prevent it, failing precisely because of a lack of funding for research. Far more lives and economic losses could have been saved if Brussels decision-makers had stuck to the drug development investment strategy they adopted after the first SARS outbreak in 2003, researchers say. Two decades later, such a short-sighted approach still prevails, leaving European citizens vulnerable to future epidemic threats.

Shortsighted politics does not help long-term research

In the period between the two outbreaks, not only in Europe but around the world, public coffers had invested taxpayers' money in several SARS research projects, including both drugs and vaccines, which ultimately never came to fruition due to funding cuts. When the pandemic began and public funding became available again, some of these promising projects were resumed and their inhibitors proved to be somewhat effective against Covid, showing that sustained research efforts could have made a difference.

“The EU and governments in general still prefer to finance reaction rather than preparation for pandemics and I think this is a mistake, especially when it comes to the development of broad-spectrum antivirals which could be manufactured beforehand and used from the start of any outbreak,” said Bruno Canard, Director at the French Scientific Research National Center and specialist of virus structure and drug-design at Marseille University.

The numbers seem to confirm this conclusion. In 2023, HERA’s budget is 1.267,6 million, including contributions from different programmes: 389 million from Horizon Europe 2023-24, 636 million from EU Civil Protection Mechanism (UCPM/rescEU) and 242,75 million from EU4Health which, with 5.1 billion over the period 2021-2027, will become the largest EU health programme ever in monetary terms (five times more than all the previous health programmes ran since 2003).

Only a third of HERA's budget, or €474.6 million, was spent on fighting infectious diseases through pathogen surveillance, pharmaceutical countermeasures and improving health systems. No more than €50 million was allocated to research and development of drugs. This figure is less than 2% of what the EC alone has paid to Big Pharma to cover part of the cost of developing covid vaccines, which amounts to €2.9 billion (including €350 million for the research phase). And it is ten times less than the 525 million spent by the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), on its Antiviral Drug Discovery Centers programme, dedicated solely to pandemic antivirals.

“Investing in drugs that can neutralise potential infectious diseases as soon as they appear is like an insurance premium, a choice between how much risk we want to take by simply letting it go and see what happens or to try to be prepared,”said said Eric J. Snijder, head of molecular virology research at Leiden University Medical Center.

The EU has paid its lack of preparedness against SARS-2 with almost 439 000 deaths and GDP decline of 6.5% in 2020, the first year of the Covid surge, and €2.018 billion mobilised through the Recovery Plan to rebuild the economy ravaged by the lockdown. It is reasonable to assume that €30 billion, the amount that the 27 Member States eventually had to take out of their safes to buy vaccine doses, would have been a fair premium to pay up front in the form of drug development and procurement.

“We cannot blame Pharma companies for not developing drugs against coronaviruses because there was no market for them back then since SARS-CoV-1 waned after a few months,” Neyts said. “I think the rich countries are to be blamed, that they did not create the necessary incentives for companies to develop drugs that can be stockpiled.”

“To stockpile ahead of future outbreaks, a drug has to go through clinical studies to show that it is safe (phase 1) and to demonstrate that it is active (phase 2) against at least a virus of the same family, for example another coronavirus,” said Snijder. “Only big companies have the capacity and funding to run such clinical studies, so they need to be involved.”

“The problem is that the most boring pandemic is the one we will have prevented from happening, because nobody will know about it. And those in power will not get any credit for countering it, let alone that they do not consider it attractive to invest a lot of public funds in things that may stop something at some point, but nobody knows when and if it's going to work 100%,” Snijder said. “Politicians tend to look 3-5 years ahead because it’s just the time for which they have been appointed or elected, while a long-term and broad antiviral drug development plan takes 10 to 20 years.”

Canard agreed: “We cannot achieve long-term tangible results with projects that usually the EU funds for up to 5 years, but I understand that scientific anticipation, which takes time, is perceived as less visible for the taxpayers than reaction.”

Promising efforts which could have mitigated the pandemic

According to the prominent researchers we interviewed, the 18 years that elapsed between SARS-1 and SARS-2 was enough time to develop a number of good inhibitor prototypes, and Pfizer has shown with its Paxlovid that it can be done in just two years if there is sufficient investment. Research literature shows that other scientists would agree with Snijder, Canard and Neyts that we might have had a chance to contain SARS-2 locally by distributing and using multi-spectrum drugs in Wuhan, and that while one can never promise that the virus would not have spread around the world anyway, at least we would have bought a lot more time for vaccine development.

Snjider, Canard and Neyts, along with Rolf Hilgenfeld, head of the coronavirus team at the Institute of Molecular Medicine at the University of Lübeck in Germany, are key pioneers in the trans-European network of scientists working on coronaviruses since the first SARS outbreak. They were part of three promising cross-border projects co-funded by the EU with a total of €30 million with the 6th and 7th Framework Programs, which could have paved the way to an effective response to Covid and changed our fate for the better. Each of them was the logical continuation of the previous one: SARS-DTV (2004-2007), Vizier (2004-2009) and Silver (2010-2015).

“The overarching principle underlying these past projects is that in peace time we cannot predict which pathogen will emerge, but we can anticipate that it will belong to one of the families of viruses we have already identified as having epidemic and pandemic potential, such as the coronaviruses (also responsible for human flu), for which we had a second warning with MERS-CoV in 2012 in Middle East,” said Neyts. “So, our objective was to develop for each of these families a broad set of potent antivirals (multi-spectrum drugs), after studying their biological structure and finding their weak points, and I am sure this was and it is still possible.”

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!