Is there any other country where the government can fall over a scandal and then that scandal plays no role in the campaign and, therefore, win the election two months later? It happened in the Netherlands, where the third government led by Conservative Mark Rutte fell over the so-called “benefits scandal” – a misnomer, as the scandal was not in the benefits but in the racists and unaccountable way in which the tax office dealt with child benefits recipients.

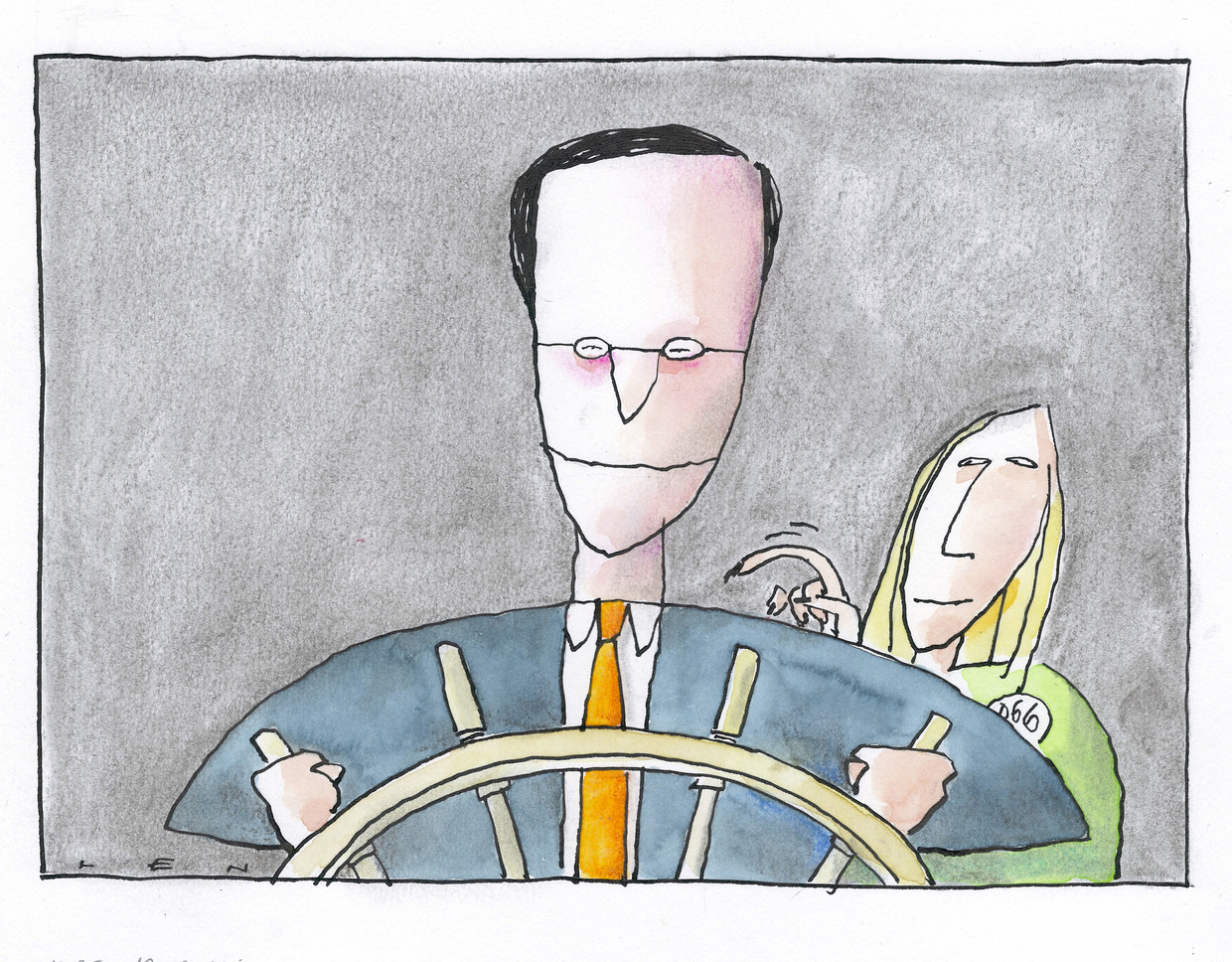

To be fair, the campaign, if one can even call it that, was about nothing really, except, perhaps, the vague issue of “leadership”, i.e. personalities over policies. And the plurality of the “critical” Dutch electorate decided that the man who had two of his three governments fall and has bungled the state response to Covid-19, including the roll-out of vaccines, is the best the country has to offer.

In many ways, last week’s election was a non-event: no campaign, no clear choices, and little change. Whereas last time the social democratic PvdA was decimated, suffering the largest loss of any Dutch party in the postwar period (29 seats), the biggest loss was just 6 seats this time. Groenlinks (Green Left) paid the price for a lackluster campaign and leader, as well as the explicit refusal to act as an opposition party in the past four years, while the far-right Forum for Democracy (FvD) returned from the dead to win 6 seats in a Trumpian anti-lockdown campaign – FvD was the only party to campaign like normal, despite strict (but weakly enforced) covid restrictions.

In fact, despite Prime Minister Mark Rutte’s claim that his “good populism” had defeated the “bad populism” of the far right in 2017, the latter scored its best result in postwar elections. In total, the far right gained 28 seats, more than the combined classic Left (25 seats). However, in line with the extreme fragmentation of the Dutch party system – a record 17 parties will be represented in the new parliament – the far-right vote is divided over three different parties. Geert Wilders’ mainly Islamophobic Party for Freedom (PVV) lost slightly (from 20 to 17 seats), and dropped from second to third place, while Thierry Baudet’s completely radicalised FvD won big (from 2 to 8 seats).