This article is reserved for our subscribers

Quantifying the exact volume of illegally caught fish entering the European Union market poses a significant challenge. Illicit fishing can be difficult to detect, while illegal catches are disguised as legal ones. Although the EU is the largest seafood market in the world, importing more than 60 percent of its consumed seafood, one in six fish arriving in the Union are not traceable.

Each year, Ghana witnesses the illegal capture and trade of approximately 100,000 tonnes of small pelagic fish, primarily comprising sardinella, mackerel, and anchovies. A substantial portion of this catch is destined for export, including to the EU market. While small pelagic fish play a vital role in Ghana’s fishing industry – and thus its food security and national economy – their stocks have plummeted by approximately 80 percent over the past two decades. Without immediate action, the stocks’ complete collapse is expected in the coming years.

A major factor in this sharp decline is the illegal fishing carried out by industrial trawlers. Most vessels are owned by Chinese businesses “through opaque ownership arrangements.” Samuel-Richard Bogobley, an expert at Hen Mpoano, a nonprofit advocating for integrated management of coastal and marine ecosystems, explains that following Ghana’s ban on foreign trawlers, Chinese fishing firms started using Ghanaian companies as fronts. They would typically arrange phoney hire-purchase deals for Chinese-owned fishing vessels. Despite their unauthorised actions in Ghana, some of these companies possess EU export licences, legally allowing them to sell their products on the European market.

Ghana boasts around 200,000 artisanal fishers and approximately 300 landing sites. Marine fisheries serve as a livelihood for around 2.7 million people and contribute to the nation's food security. Artisanal fishermen primarily target small pelagic fish near the shore and in the open ocean's upper layers, accessible to their wooden canoes.

Although the Ghanaian government has taken some steps to combat illegal fishing, such as launching a web application to report it, it is not sufficient to reverse the trend. The EU could also contribute more.

How did the fish stocks decline so much?

In 2002, Ghana established an Inshore Exclusive Zone for artisanal fishers, aiming to protect stocks of small pelagic fish. Despite this, industrial vessels with licences for bottom-dwelling fish continued illegal fishing. Since they cannot bring back to the shore the captured small pelagic fish, the Chinese-owned companies sell it at sea to small artisanal fishers, who are legally allowed to fish it and bring it to land. This is done through a practice called saiko.

Bogobley explained that this allows the trawlers to bring only legal catches alongside a limited proportion of by-catches, including the small pelagic fish, thus meeting the Ghanaian port authorities’ landing requirements. The practice of saiko has “developed into an industry of its own,” he says, in which both the trawlers and the artisanal fishermen are active participants. The fish legally brought back by both trawlers and artisanal fishermen then gets shipped to the European market. Seemingly everything is in order.

While the majority of the businesses are Chinese-owned, European boats and operators are also involved in illegal activities in Ghana. European fishing vessels are difficult to trace, however, because they are often re-flagged to non-EU countries.

Vessel reflagging occurs for two main reasons: to secure fishing quotas from other states via Regional Fisheries Management Organisations (RFMOs) or to bypass fishing authorisation requirements in the waters of non-EU countries where sustainable fisheries agreements (SFPAs) exist. SFPAs are negotiated by the EU Commission. However, if a vessel is re-flagged to a non-EU country, an EU operator can set up a private agreement to continue fishing in SFPA-covered waters.

An example of re-flagging is the super-trawler Franziska, owned by the Dutch company Willem Van der Zwan en Zonen, which has a subsidiary in Ghana. This trawler has switched flags multiple times, going from Dutch to Peruvian between 2009 and 2013, before returning to the Dutch flag.

To make matters worse, the European trawlers are fuel-tax exempt, thus indirectly costing EU citizens funds that could be invested elsewhere, including in sustainable fisheries. From 2010 to 2020, the EU’s fishing fleet enjoyed a fuel-tax exemption of about €15.7 billion.

Re-licensing and legally exporting to the EU

Concerning Ghana, Bogobley decries the government’s lack of transparency in its handling of companies engaged in illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. He stressed: “As a nonprofit organisation, we are not given access to the list of companies that are engaged in illegal fishing activities, so we conduct our own investigations. Also, whenever a company is caught engaging in illegal activities, the preferred solution is out-of-court settlements, instead of a public trial.”

Despite repeatedly engaging in illegal activities and refusing to pay fines, some companies have been re-licensed to continue operations in Ghanaian waters. Subsequently, they are allowed to export their products to the European market.

For example, Chinese company Rongcheng Ocean Fishery's trawler Lu Rong Yuan Yu 956 was caught fishing illegally twice. In 2019, the vessel was found using illegal nets to catch small pelagic fish and was fined $1 million, which the owners did not pay. In 2020, the trawler was arraigned for “almost identical offences”. A similar example is Shandong Zhonglu Oceanic Fisheries Co., whose vessel Long Xian 608 was caught in 2019 carrying juvenile fish and obstructing its net. The company paid $2,450 of the $12,000 fine.

The failure to hold these companies accountable in both Ghana and Europe has fostered a culture of impunity, further encouraging them.

What is the impact of illegal fishing?

Faced by competition with industrial vessels, artisanal fishermen are forced to go further out to sea and to stay there for longer periods of time – up to two or three days. They risk their lives for catches so low that their fuel costs are barely even covered.

As fish landings decrease, fish prices rise. This poses a significant problem for Ghana since seafood constitutes about 60 percent of Ghanaians’ protein intake. With the ongoing global inflation, accessing nutritious and diverse food may become increasingly difficult for Ghanaians.

Reduced catches lead to fewer job opportunities for those involved in fishing. This drives many fishermen to leave the coast and seek opportunities in precarious and informal sectors within or outside the country.

Illegal fishing pushes the pelagic fish themselves towards species extinction, while also contributing to climate change. Ska Keller, a German MEP, stressed that, “when fish stocks are depleted, the oceans are less resilient and we benefit less from the services they provide, such as climate regulation”. The depletion also threatens delicate marine ecosystems, as it disrupts the food chain with other species that rely on the decimated ones for sustenance.

Measures in place and measures to consider

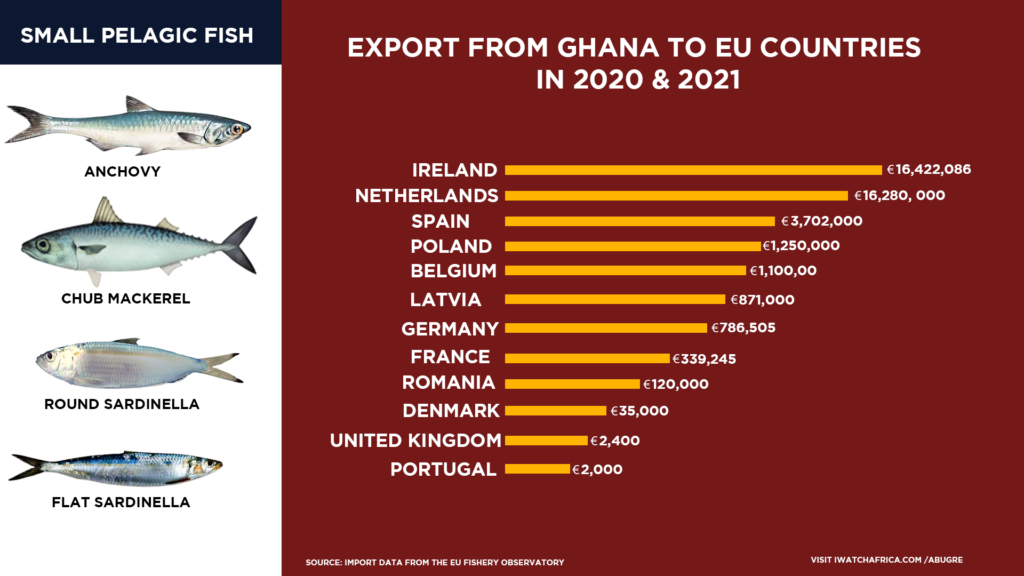

The decline of Ghana's small pelagic fish impacts the EU, a major importer of Ghanaian fish. To combat IUU fishing, the EU has enacted the IUU Regulation, banning illegal fish imports, and signed agreements with Ghana to promote sustainable fisheries.

In 2021, the EU issued Ghana its second “yellow card”. This card marks a formal warning that, if IUU practices continue to be left unaddressed, the country could be banned from accessing the EU’s market. Ghana received such a warning in 2013, which was lifted in 2015, and is now the second country to ever be issued another.

MEP Keller emphasised that the carding system “has proven to be useful, but there are still loopholes that need to be closed – for example, vessels flagged by a 'non-cooperating country' can be reflagged to another country. In addition, the EU should make member states apply dissuasive sanctions to carded countries as well as import controls in a consistent and robust way.” She highlights the EU’s need to tackle its fleet’s misreported catches and ensure compliance with landing obligations. They are applicable since 2019, but poorly enforced.

Following its second yellow card in 2021, Ghana's Ministry of Fisheries and Aquaculture Development boosted surveillance and monitoring. Steps included installing cameras on trawlers, recruiting personnel to analyse the collected data, and increasing the number of government observers accompanying trawlers at sea.

Hen Mpoano’s Bogobley emphasised that, while this latter initiative is useful, the number of observers is still very limited and they are underpaid, making them prone to bribery. With EU backing, Ghana also created the DASE monitoring app. Artisanal fishermen can use it to share photos of illegal trawling, enabling the government to counter IUU activities effectively.

To secure the long-term sustainability of Ghana’s small pelagic fish, further action is imperative. According to MEP Keller: “For the EU, allowing illegal fishing is politically inexcusable. We are striving to set an example of high standards and good governance, and we have to do everything in our power to prevent these activities.”

This investigation was supported by Journalismfund Europe

This article is published within the Come Together collaborative project

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!