Lucie Pinson has worked on questions relating to the energy transition and finance for a number of years. Prior to this, she led campaigns focusing on the responsibility of finance in social, environmental and climate injustices. She has worked for Friends of the Earth and the Sunrise Project. In 2020, she founded the NGO Reclaim Finance, which campaigns to decarbonise the financial sector and put it at the service of social and climate justice. She was the laureate of the prestigious Goldman Prize (dubbed the "green Nobel") in 2020.

To what extent is finance a "critical lever" in the fight against climate change?

Money is everything. To see the light of day, an infrastructure project – be it a school, a railway line, a hospital, an oil platform or a gas power station – needs financing and insurance cover.

Avoiding climate breakdown and making the transition to sustainable societies requires massive investment: more than €406 billion a year between now and 2030 for the European Union alone. The transition will only happen if it succeeds in attracting the necessary investment, and is insured. Big finance therefore has a responsibility. This is recognised in the Paris Agreement, which calls on the sector to align itself with climate objectives. In practical terms, this means acting on two levels: increasing funding for "green" solutions, but also winding down the funding for polluting businesses which must eventually disappear.

Another essential factor is the need for sobriety. We will only avoid a crash if we reduce energy consumption at a global level. Here the financial sector can play a role, because this also requires specific investments. But politicians must act first to ensure that the main effort is asked of the most affluent – who are by default the biggest emitters – and not those whose fundamental rights are already at risk.

For the energy sector, the aim for 2020 is to invest ten euros in the transition, including six in sustainable electricity production, for each euro invested in fossil fuels. Beyond the amounts, there is the question of quality, of what is actually funded. The six euros should be focused on wind and solar power, without forgetting the grid and storage. As for the one euro that will still have to go to fossil fuels, it should be spent on existing infrastructure and especially on technologies to reduce emissions – and absolutely not on developing new infrastructure.

In short, funding has to be allocated with great care. But neither is this just an exercise in logistics. It is first and foremost about politics. The solutions exist, and investors know it. If they are still channelling massive sums into the expansion of fossil fuels, that is simply because they have decided to prioritise their short-term profits over any social or environmental considerations.

What (and how much) are we talking about when we refer to "green finance"? Is it not an oxymoron?

The growth in climate-friendly commitments by international investors has coincided with a growth in rhetoric about "green finance" or "sustainable finance". These terms mostly refer to financial products and services that support sustainable initiatives, or at least ones that are selected on the basis of extra-financial criteria. This is in contrast to traditional financial products, which are judged purely on grounds of their financial returns.

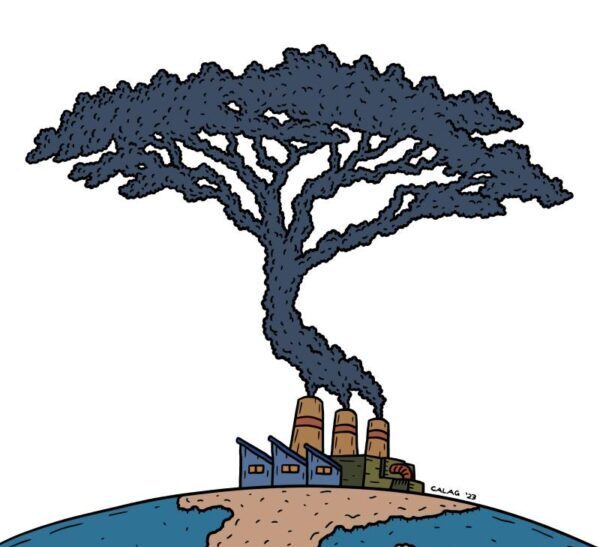

Obviously, abusive use of these terms can amount to greenwashing. In addition, "green finance" as I have just defined it does nothing to address the root cause of climate change, i.e. the excessive release of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere via polluting activities that are incompatible with 1.5°C of global warming. The very term can sound like a confession of guilt on the part of the financial sector, which is well aware that traditional finance is at odds with the sustainability objective.

The growth in climate-friendly commitments by international investors has coincided with a growth in rhetoric about “green finance” or “sustainable finance”

Unfortunately, this term has become the focus of so much hype as to distract attention from the investments that continue to worsen our predicament. It is true that we are seeing the emergence of official labels and attempts at national and European level to regulate the use of terminology and the content of products labelled "green". But in concrete terms little has been done to force investors to stop supporting projects and companies with business models that are incompatible with the objective of limiting global warming to 1.5°C.

This situation suits the interests of financiers well, especially those most heavily exposed to hydrocarbons. Not only does green rhetoric divert attention from their most climate-damaging products, it also means new markets and thus new opportunities for growth and profits, this time on ostensibly green products which procure prestige.

There are already instruments, such as the European Green Finance Regulation (SFDR), which impose standards on banks when defining the financial products offered to investors. Alas, as shown in Voxeurop's reports on green finance, the SFDR is written in misleading and ambiguous language that leaves it open to abuse.

What do you see as the role of institutions? Are there any clear issues at stake in the run-up to the European elections in June?

The European Commission's previous term of office was that of the Green Deal; the next must be that of its strengthening and, above all, its financing. The issue has been largely ignored until now. Bodies such as the International Energy Agency (IEA) and the European Commission agree that 80% to 85% of the financing needs for the transition must come from the private sector. Public intervention will be essential to force financial players to make the right asset-allocation choices.

There is no shortage of money, but it will not be directed towards climate solutions without proper regulation. And not just any regulation: we need to move away from regulation that is limited to demands for transparency and reporting, and towards regulation that puts politics front and centre. It must shape the behaviour of financial institutions and the businesses they fund.

The outgoing commissions could have made it compulsory for financial players to adopt proper plans, in particular through the directive on corporate duty of care. But that directive ultimately excluded the financial sector, largely thanks to the French economy ministry and France's EU presidency.

As on many other dossiers, the French government cynically reneged on the 2019 campaign pledges of its own candidates and went against the votes of its own parliamentarians: in the EU Council France opposed regulation of the financial sector despite a majority vote in favour by MEPs in the EU Parliament. It seems that campaign promises are only binding on those who believe them.

In June, voters will be best advised to choose on the basis of what has been voted for and supported by the various parties over the last five years. As for groups like Reclaim Finance, we will be looking beyond the elections, and we urge others to stay mobilised too. These elections will kick off another five years of struggle to put European finance at the service of social and environmental justice.

Who are the most important players? The banks are at the centre of our economy.

Banks play a key role because they hold the purse strings. Even though securities and bonds are bought by investors, their issuance on the markets requires the involvement of banks. And yet European banks continue to work against the international climate objectives, as well as those of their own countries and the EU. Since the last European elections, the EU's top 15 banks have provided more than €170 billion to the hundred or so companies at the forefront of the fossil-fuel industry. Two-thirds of this comes from the four major French banks, which have made progress on coal but very little on oil and gas.

Of the 15 French banks that have financed fossil-fuel expansion in recent years, how many have committed to ending that investment in the future, in line with the scientific recommendation and projections by the IEA? Just one. And none has committed to the 2030 target of investing six euros in sustainable energies for each euro allocated to fossil fuels.

This despite the fact that banks are now coming to terms with the science. For example, the CEO of Crédit Agricole publicly acknowledged at the group's last general meeting that oil and gas expansion was not compatible with limiting warming to 1.5°C, and that his bank could not just turn a blind eye to the new hydrocarbon projects of the sector's giants. And yet the bank still finds a way to finance them: even today it is directly funding the construction of liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminals. The Banque Populaire Caisse d'Epargne group is perhaps an even worse foot-dragger: it recently took part in a $4.25 billion deal for TotalEnergies, money that will go to oil and gas – in particular, to the development of new LNG fields and terminals, to which TotalEnergies still allocates two-thirds of its investments.

What solutions and tools do we have to deal with this?

The solutions exist. All that remains is to make them happen, and that will only be possible by taking on the institutions in place. In the area of finance, people often talk about the importance of changing one’s bank or choosing financial products that are good for the planet and human rights. Such actions are indeed important, but they only become really effective when carried out collectively through political action. So it remains essential to speak out and mobilise collectively to demand that we regain control of our own money and of finance in general.

What progress can we point to?

We can welcome the introduction of double materiality, through the European Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD). Double materiality means that financial players must pay attention not only to the financial risks to which they are exposed – for instance, those linked to climate change – but also to the impact of their investments on the climate, human rights and ecosystems.

But so far this remains a simple exercise in transparency. It needs to be extended to include an obligation to adopt proper transition roadmaps. These should indicate, in particular, how a financial firm intends to align its business with European and international climate objectives. The plan must also specify how the company intends to wind down its investments in polluting businesses, to increase its investments in green solutions, and to assist the transformation of sectors that – as with steel and electricity generation – have a future provided they decarbonise.

Do you like our work?

Help multilingual European journalism to thrive, without ads or paywalls. Your one-off or regular support will keep our newsroom independent. Thank you!